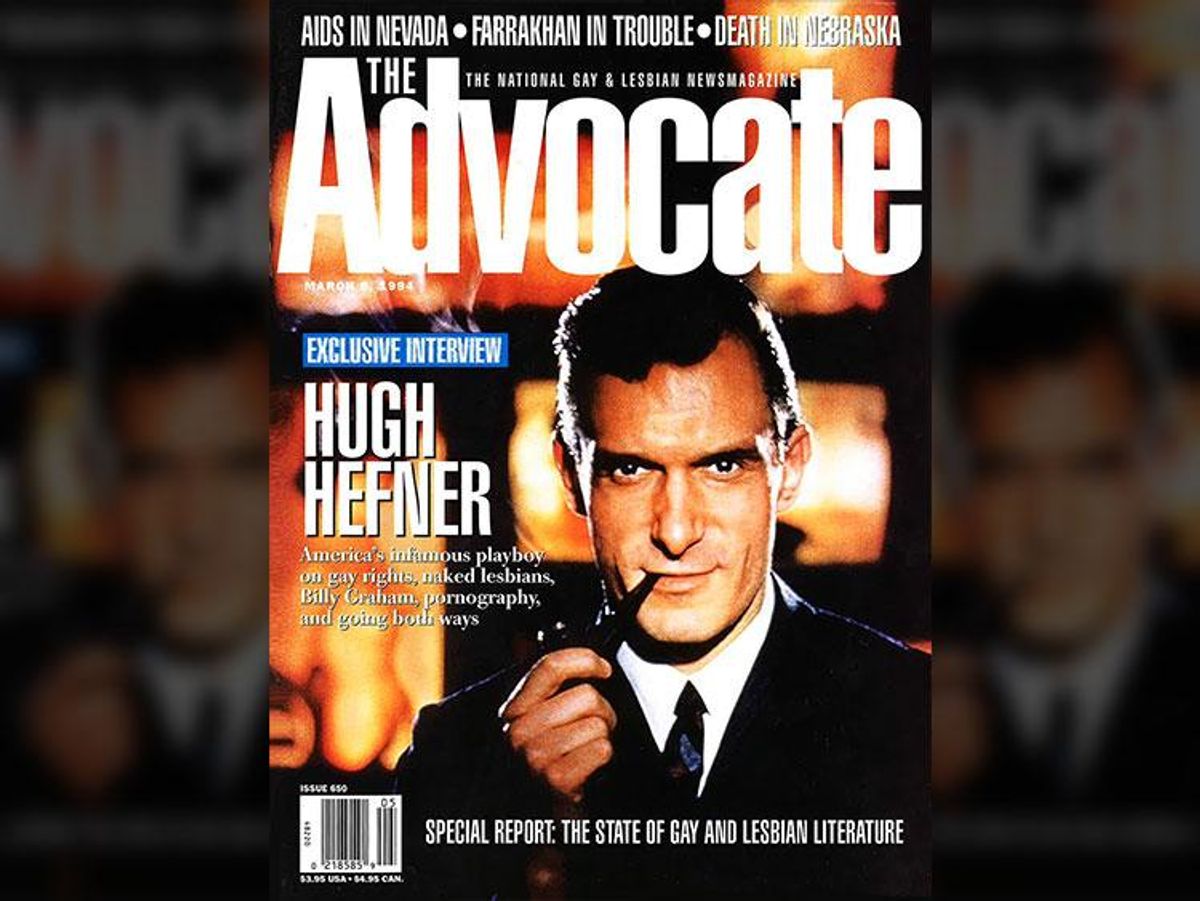

"Please come alone," I'd been instructed prior to my ascent up a quiet road in Holmby Hills, the toniest of Los Angeles neighborhoods. Passing through iron gates and cruising by bear-like guards, the Mansion loomed as I drove solo up to its motor court on a marine layer-cloaked day in February 1994. I'd been after an interview with the iconic estate's infamous owner for almost two years. The chase had run parallel to another long-term pursuit, Elizabeth Taylor (who came into the fold a few years later). Oddly -- these two most-fascinating people were allied in the fight against AIDS. As opposed to Taylor, Hugh Hefner was, at the time, a conquest many around me at The Advocate didn't understand. But the truth was, without Hefner, there may not have been an Advocate. His decades-long, relentless fight for freedom of the press, for sexual frankness, for sexually based advertising, and for controversial subject matter paved the way for an activist press.

Do you still receive your hard copy of a gay magazine covered by an opaque coverlet? Hefner pioneered this process of mailing to protect the privacy of his subscribers. He also fought -- as The Advocate's ownership had -- with magazine distributors (and with the U.S. Postal Service) to get his product delivered to a hungry readership. Hefner battled for (and many times lost) shelf space on newsstands. His magazine was summarily banned countless times in Southern states. During my tenure as editor in chief of The Advocate, our magazine was pulled twice from newsstands in the South; for the cover stories "Is God Gay?" about Jesus' tolerance of sex workers and outcasts, and for "The Outing of Jim McCreary," an investigation that laid bare a conservative politician's double life.

You may have noticed, I haven't mentioned Playboy until now. But you knew. Among America's magazines, Playboy is the most well-known, the most common butt of jokes on late-night TV, and a frequent subject of childhood sexual anecdotes. Marilyn Monroe was nude on its first cover. Anna Nicole Smith and Pamela Anderson were among its many discoveries. At the height of its prowess, it routinely sold between 6 million and 7 million copies a month. Successful periodicals today are thrilled with 300,000. Playboy was as well-known for its bare-breasted beauties as for its provocative interviews with everyone from Malcom X to George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party. Fidel Castro, Warren Beatty, and Larry Kramer spoke to Playboy too. If you were asked to be interviewed by Playboy, you were "it."

Those of us growing up gay in the late '60s and early '70s looked to Playboy for clues about our burgeoning sexuality -- just like our straight brothers. In the magazine's pages, men were pictured semi-nude (mostly still photos from X- and R-rated films) and were shown as naked cartoon characters having sex with Little Annie Fannie. Where else -- at 9, 10, or 11 -- could we sneak looks at such provocative imagery? My first masturbatory experiences were with a Playboy in one hand. And I wasn't looking at Miss July.

This place smells, I thought, as I was ushered through massive, hand-carved doors into The Playboy Mansion's foyer. The home had the air quality that comes along with too many parties. "Mr. Hefner is in there," said an aide, who pointed me down a floor to ceiling paneled hallway. Seated on a blood-red velvet cushion was the publishing industry's all-time VIP. Behind him were leaded glass windows that revealed rambling green grounds. His wardrobe did not disappoint: silk pajamas and crested slippers. No one in American history had attained his level of visibility as a magazine purveyor. "Hey, man," he said, "I liked your interview with Oliver [Stone]. He's a warrior." Martinis arrived (at 2 o'clock) on an engraved silver tray. And a rambling, two-hour discussion with the playboy began.

He talked openly about his personal brushes with homosexual sex acts (Liz Smith lost her mind over this one), his engagement with a nefarious federal government intent on shutting him down, and how he's been misunderstood by feminists. He said provocatively, "The only thing wrong with AIDS is the way our government responded to it," "God is nature," and "Political correctness is having a major impact on our society." He was annoyed that in America sex was "getting a bad rap" and "Puritan ethics" were proliferating. He felt an alliance with the gay rights fight. When discussing sodomy laws: "You and I know what crimes against nature are, and they don't include consensual sex acts. Try raping the planet's rain forests."

As is the case during most interviews with A-listers, there is a pre-planned intercession that brings them to an end. The aide who had brought me into the Playboy's lair poked his head through an almost-hidden door and said, "Pardon me, sir, but Christie's on the phone." "Ah," exclaimed Hef, "the boss," referring to his business heir-apparent and daughter, Christie Hefner. Real or manufactured, this was my nudge. "I admire what your community has done," said Hefner, as I gathered my implements. "I've always felt like an outsider myself. Like I had something to prove." His journalistic activism suddenly took on a different light. Was this man searching for personal acceptance -- despite the women, the celebrities, jets, clubs, and fame? "Nothing comes without pain," he said with a wry smile, shaking my hand goodbye. "No pain, no gain, you know?"

JEFF YARBROUGH was editor in chief of The Advocate in the 1990s.