Voices

I Will Never Forget My First Gay Friends

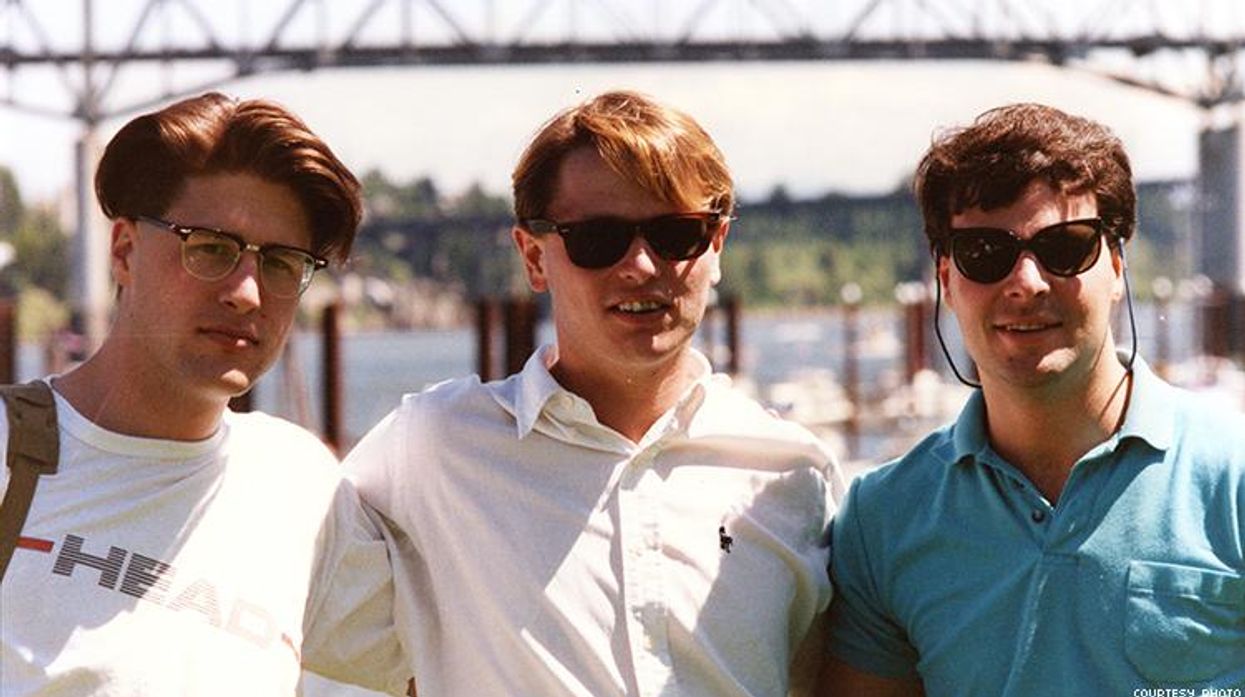

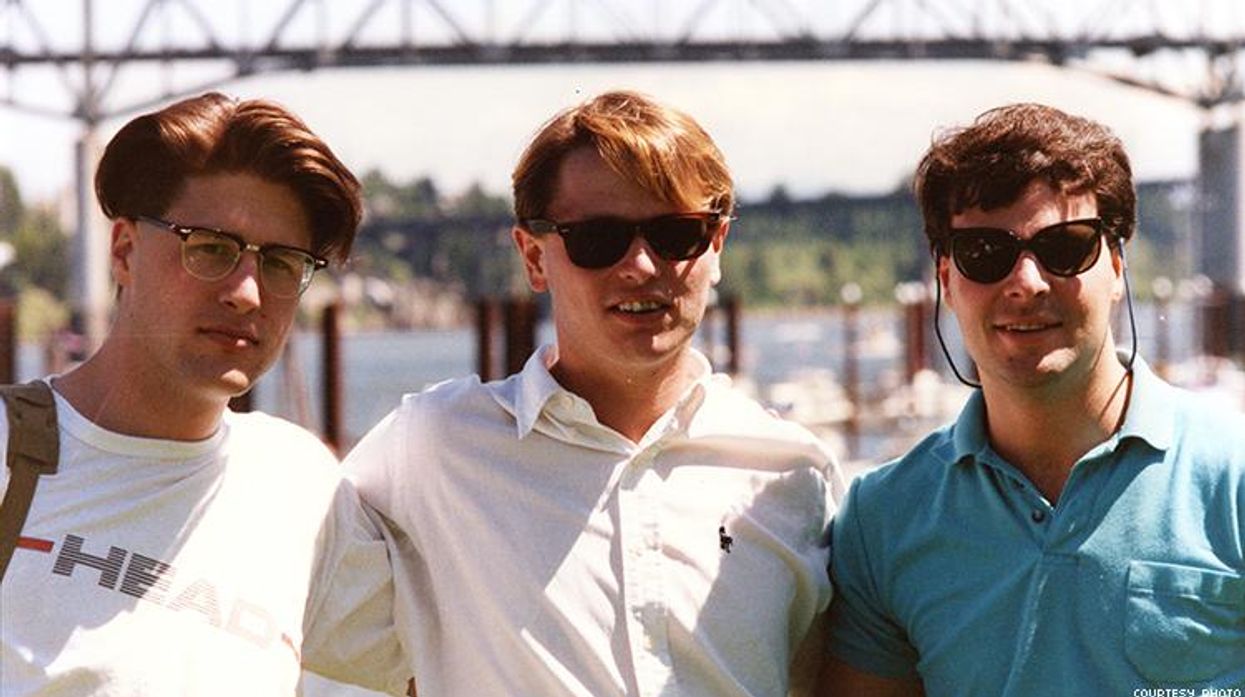

Michael McShane, a federal judge in Oregon, shares how the members of an informal book club, the Alice B. Toklas Society, changed his life.

January 25 2018 5:19 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Michael McShane, a federal judge in Oregon, shares how the members of an informal book club, the Alice B. Toklas Society, changed his life.

There were five of us who made up the Alice B. Toklas Society. All of us had arrived in Portland in the early 1980s and all of us were awkwardly gay and awkwardly in search of an identity and a career. The youngest of us, Scott, was 19 and would become what I imagined at the time to be my life partner. At age 23, I was the oldest of our cohort and the only one who had finished college and held a steady job. To this day I secretly suspect that the origins of what ultimately became deep friendships began with the fact that I was the only one among our group with an apartment to myself and a salary to invest in alcohol.

We spent most of our nights (weekend or otherwise) drinking in whatever gay club was advertising the best drink specials and willing to look past Scott's fake ID. On Sunday night it was 50-cent schnapps at Slaughters; on Monday it was two-for-one well drinks at the Embers. It went on like that all week in various venues where we and a hundred other budding alcoholics would meet and sometimes dance and sometimes talk and mostly try to get laid. Among the five of us who would make up the Society, our favorite pastime was to complain about the bars and everyone in them.

But if truth be told, we were no better or different than anyone else in the bars; we simply wished we were. We were big wishers. We imagined that we were competent and creative, that someday we would be successful, and that we would find the right man who was not the guy you blew in the bathroom stall the night before. Mind you, nobody was complaining about the drugs and the sex and all that, but we hated the fact that it seemed to be what drove our lives. Deep down we knew what purported to be a celebration was but a few years away from tragic desperation if something did not change.

So we formed the Society as our protest against the lives we had been living. We started a weekly book club that would meet at my apartment in northwest Portland. In summers we sat on the rooftop in lounge chairs and in winters we would huddle around a very small gas fireplace in my studio apartment. Looking back on it, we were hardly a disciplined group of intellectuals coming together for the sake of literature. It was a far cry from that. Yes, our meetings were part thoughtful reviews of our assigned book, but it was not long before they regressed into part therapy session or part gossip fest. Peter would have to unburden himself with great flourish about the lifetime commitment he had just made or just lost; Mike was worried about whether he would make the university's relay team in the 1600 meters; Richard was just one more casting call away from moving to L.A. and a career in Hollywood; Scott could not decide if he should give up dancing and go back to school. With my application to law school, I seemed to be the only one among us who had a clear trajectory toward the future.

The origin of our society's name came from Peter. Each week allowed one of us to select our assigned reading without objection from the others. Because we were so different, we read through a wide variety of literary genres. Richard, for instance, liked even the silliest of mysteries, requiring us sometimes to read all but the last chapter of an Agatha Christie novel. He would then offer a blow job to anyone who could guess the identity of the killer, leading all of us to pick the least likely of culprits, typically the one Christie made appear the most culpable. Mike, who fancied himself very progressive, had us reading every piece of women's literature that came out of South or Central America. At one point, to emphasize the spiritual nature of the genre, he had us hold a seance to invoke the spirit of Isabel Allende. I did not have the heart to tell him that she was not yet dead. Novels that were unfamiliar to him often daunted Scott, who grew up poor and had never finished high school. He preferred the samplings of his favorite poets, many of whom I introduced him to. He would practice the alliterations of Gerald Manley Hopkins for hours prior to reading them to us. He was terribly self-conscious about appearing uneducated. I, having been educated by Jesuits and being just a bit full of myself, returned us to the great classics, marching us through Lattimore's translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey at a breakneck pace that caused constant complaining from the others.

But when the rotation fell to Peter there was never a doubt what we were going to read.-- it was always Gertrude Stein. Peter loved her with such a passion that we took to calling him "Alice" after the name of Stein's lesbian lover, Alice B. Toklas. Peter would start his rotation with great drama by standing up and, in the dying last words of Stein to Toklas ask, "What is the answer?" We, playing the role of Toklas beside Stein's deathbed, would sit silent. After an appropriate pause, he would place his hands brashly on his hips and haughtily inquire, "In that case, what is the question?"

We could then, and not until then, begin our groaning discussion of why, despite our poor Alice's attempts to sway us to the contrary, we hated Gertrude Stein so vehemently.

Occasionally for fun we would take on the character names of our particular literary devotion during our meetings: Dashiell, Isabel, Hopkins, and for myself, Odysseus. But it was Peter, his focus on Stein unwavering, who found himself being called "Alice" both in and outside of our book club. I suppose that his affinity for dressing in drag made this seem a more natural fit. In any event, at some point we had read and reread so much Stein that we found ourselves bowing to his request to coronate ourselves the Alice B. Toklas Society. I think it helped that Peter also had us convinced that Toklas was responsible for baking the first brownies laced with marijuana. It was, we reasoned, the only way that she or we could manage to love Stein, and we would eat them with great relish when our own Alice's week would arrive.

We would meet this way as a group for almost two years. But, as it does with the young, life would change with each season. Scott moved in with me, left his dreams of dance, and worked as a waiter in two restaurants so that I could finish law school.

Mike would continually make the sports pages in the local newspaper, but his dreams of Olympic glory were beginning to fade. Richard repeatedly auditioned for parts that he hoped would lead to a life of stardom, but nothing ever seemed to come his way. He eventually took a job at one of the big chain video stores, ironically called Hollywood Video. He would often joke that he had finally made it to Hollywood, but there was always a bit of sadness behind his humor. Peter, being Peter, fell in and out of love at least 10 times, swearing each time that he would never fall in love again. I passed the bar exam and became a public defender with a modest salary, but one that finally allowed Scott to give up waiting tables and focus on school. The first class he registered for was Intro to Shakespeare: The Tragedies. We would spend our evenings reading out the parts of each drama on the couch. Sometimes Peter would join us. His drag queen rendering of Desdemona was second only to his Lady Macbeth.

All would die within three years of each other, Mike being the first. His death was perhaps the hardest, or at least the most surprising, because he was the one true athlete among us. He was young, as lean as a jaguar, and had an enduring energy behind a disarming, boyish smile. We had had what he referred to as "a lovely entanglement" before Scott came into my life. For me the reality was a little more complicated and painful; I remained embarrassingly in love with him. I have never really untangled Mike. I remember the taste of his body so clearly that it still hurts.

He called me from Anchorage where he was visiting his parents. He complained of a bad cold and was feeling miserable. He was unable to manage a morning run. The next call came and he had pneumonia and was to be admitted to the hospital. That was the last time I would talk to him. He told me he was reading a John Irving novel called A Prayer for Owen Meany and would like to send it to me. He went into a coma shortly after and was dead within two days. He would never learn that he had developed AIDS, and his parents learned for the first time that their dead son was gay. I sent a mass card and wrote several letters to his mother, but none received a reply.

Richard finally moved to L.A., where he found a couple of small parts in television commercials. He often joked that he was ready and willing to do porn, but his dick was so big that it scared away the big-name stars. He was an eternal optimist despite his lack of acting talent. I often wonder if Richard ever truly believed he would make a name for himself in Hollywood or if he just got trapped in the role of believing it.

He returned to die at his parents' house within 11 months of leaving Portland. They were Christians living in a small town near Eugene and preferred that we not visit. He passed his last days in silence, surrounded by a bitter and embarrassed family. We never said goodbye.

Peter went into hospice care in Portland, where he spent six months declining with all of the drama his frail body could manage. Scott and I would visit him often and always on Fridays, the night that the Society had met but a few years earlier. And yes, he would insist and we would oblige him with a reading of Gertrude Stein until he could not longer stay awake.

I wish I could tell you that his last words were those of Gertrude to Alice; he instructed us to say as much if anyone were to ask. In reality, what was said was what needed to be said. About an hour before he slipped out of consciousness, he simply looked at us and whispered frailly, "I love you guys." Dropping all pretenses, I put my head on his chest and, using his real name for the first time in years, replied as simply: "I love you too, Peter."

Scott died at home in a hospital bed that was made up for that very purpose. It was a long ordeal; his once tall and muscular frame withered away to just over 80 pounds. Even now I cannot speak much of it except to say that he died quietly in my arms. The last poems that I read to him were his two favorites, "Pied Beauty" by Gerald Manley Hopkins and "Birches" by Robert Frost. I read both of them at his funeral.

As for me, I am now 55 years of age. After my career as a public defender, I went on to become a judge. I raised a son and now find myself raising a nephew. I went through a couple of serious relationships and have now settled down with a man I love deeply. I have developed some great friends, and I am well thought of in my profession. Life has been kind to me. It is neither remarkable nor unique, but with each passing year I cannot help but believe that the gods have smiled on me and granted me a place to find love and happiness in a world where such things do not always come to pass. It still feels to me a place less built than given, profoundly so through the blessings of those who left me years ago.

Sometimes I cannot bring myself to remember the life I lived as a young man and the faces of those four friends that shaped it. The beauty, the vibrancy, the potential of it all -- at times I collapse under its weight. I wonder sometimes how I can go on with this other life in light of what was lost.

I know it sounds foolish, but it is in these times I pretend myself to be a true Odysseus -- the solitary hero who survives and returns home when all seem to perish around him. And as with Odysseus, a home inextricably continues to wait for me at the end of each day. It is hard not to dwell on the unfairness of it all. It is hard not to dwell on the memories of those four young boys.

The one constant from my youth remains the writings of others and the strength of their words. And as I read now, I remember with fondness the young men who read with me those many years ago. I still enjoy Dashiell Hammett and Isabel Allende. I continue to agonize, albeit lovingly, over Gertrude Stein. But it is in Scott's poems that I find the greatest comfort:

Life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig's having lashed across it open.

I'd like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth's the right place for love:

I don't know where it's likely to go better.

As I read again these words of Robert Frost, an old dog yawns loudly at my feet. The soft hum of a video game drifts down from my nephew's room despite the fact that it is well past his bedtime. My husband has fallen asleep on the couch, having forgotten that I poured him a glass of wine an hour ago in the hope he would join me in the study to read. Outside I hear the whisper of the Oregon cottonwood in a late autumn breeze, and a night heron cries by the banks of the river.

Tonight I am a quiet Odysseus, the margins of an untraveled world fading forever as I move.

Tonight I have found my way home.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes