I am in the middle of "Kemp country." That's Brian Kemp, the new governor-elect for the state of Georgia. Kemp country is a place which, according to the "certified election results," voted for the white Republican candidate handily. I am the only black face here, which feels strange because it's rare that I am the only black face anywhere I go these days. I'm not in Atlanta anymore, but Georgia, a distinction those of us in our Southern blue bubble understand too well.

I came here to St. Simons Island to support my boyfriend, who had a series of meetings in this sleepy town. I also came, out of a sense of curiosity. Who are these people so unwilling to vote for Stacey Abrams, a candidate that was by far more qualified, more intelligent, and more compassionate than her opponent? A candidate who would have ensured better healthcare, economic growth, and educational opportunities? Versus Kemp, a man who didn't resign as Secretary of State, in a close race, despite the appearance of conflict.

I needed to look white supremacy in its ugly face. Coastal Georgia, at least the parts that are Kemp country, is very different from Atlanta. When my boyfriend and I checked into our hotel, the nice lady behind the counter didn't understand why we were checking in together. When she realized we were a couple, her smile became more tense. Her eyes would no longer land on us. "Enjoy your stay," she said avoiding eye contact. Her tone perhaps revealed more than she intended.

"Thank you, we will," I replied, then smiled back with the sincerity of a pageant contestant. Perhaps black gay men didn't invent shade, but we certainly perfected it.

Don't get me wrong. Their voices are polite, but history is filled with smiling people doing horrific things. Look at old lynching photos. Politeness in the South is a performance -- a mask, and at times, a weapon. They will offer you sweet tea, then call the cops on you.

If Stacey Abrams had won, it would feel safer, even if such feelings were only an illusion. Black people get shot in plenty of cities that have black leaders. That was true during the Obama era, too. And yet, that illusion would have been preferable to the frightening reality.

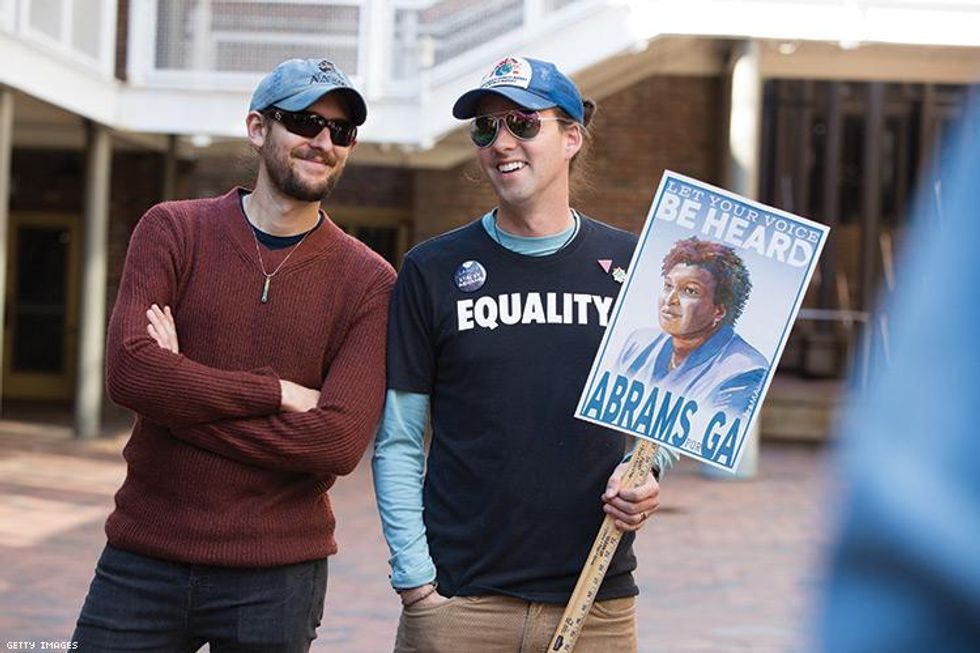

We, the coalition and honorable resistance, that Abrams forged to become the top Democrat vote getter in the state's history -- people of color, young people, working-class folks, progressives, and LGBTQ folks -- will continue to be under attack in a state that has chosen to strap itself to the past.

In Abrams, we allowed ourselves to dream. While she is not a member of the LGBTQ community, she is perhaps one of the greatest allies we have ever had in a politician. If elected, she would not only listen to us, but she would hear us. Abrams showed us that you can be different and you don't have to fit a traditional political model, that you can embrace your difference boldly, and in your difference find a source of power.

So many people wanted Abrams to fall in line. They wanted her to concede, instructing her in the media to be good, to be docile, to give up. And she refused.

She discontinued her campaign, but never conceded, in one of the greatest political speeches ever, and one of the most stunning acts of defiance of this century, she essentially said: "No, I won't go away quietly." Abrams won't disappear. Nor will her coalition. She will continue to fight against voter suppression, and so will we. She's shown us the way.

Contributing editor CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. He is also the executive director of the Counter Narrative Project. Follow him on Twitter @CharlesDotSteph.

Contributing editor CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. He is also the executive director of the Counter Narrative Project. Follow him on Twitter @CharlesDotSteph.

Contributing editor CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. He is also the executive director of the Counter Narrative Project. Follow him on Twitter

Contributing editor CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. He is also the executive director of the Counter Narrative Project. Follow him on Twitter

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes