It's old news now that 2020 presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg told a reporter that he couldn't even read the LGBTQ media anymore because it was obsessed with whether he was too gay or not gay enough. He later blamed the episode on his grumpy morning nature. I was disappointed I didn't get a chance to challenge him on this myself at the LGBTQ Forum that The Advocate hosted last week. I think it's a classic case of someone speaking without having all the facts. The press that have speculated about what kind of gay man he is or isn't have largely been mainstream outlets like The New Republic, even if they've employed other gay men to do so. (In that case, Mayor Pete should remember the writer of that TNR "satire" is an author and book critic, not a political pundit or policy wonk by any means.)

I suspect though that Pete Buttigieg is a bit on edge because he knows that just as President Barack Obama was the man to make it for African-Americans, Pete is just the kind of LGBTQ candidate that will become the first of us to make it to the White House. He's a white, Christian, upper-middle-class, monogamous, non-threatening, and easy on the eyes man with a homespun Midwest sensibility that makes people like him. I like him. And I'm sure he knows that he has that privilege and it is weighty.

But with it comes the responsibility of remembering all the "radicals" that got him to that position: the gay rights activist Barbara Gittings marching in the streets, AIDS activists Sean Strub and Peter Staley hoisting giant condoms over a congressman's house, lesbian literary icons like Audre Lorde who spoke out until their premature deaths (from health issues that plague our underserved community), the bisexual performers like Josephine Baker who helped bring an end to World War II, pioneering activists including Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson (the latter, one of so many murdered Black trans women) paving the way for transgender women today, civil rights activist Bayard Rustin helping launch the movement, politician Harvey Milk -- a flamboyant and feminine gay man who couldn't help but "sound gay."

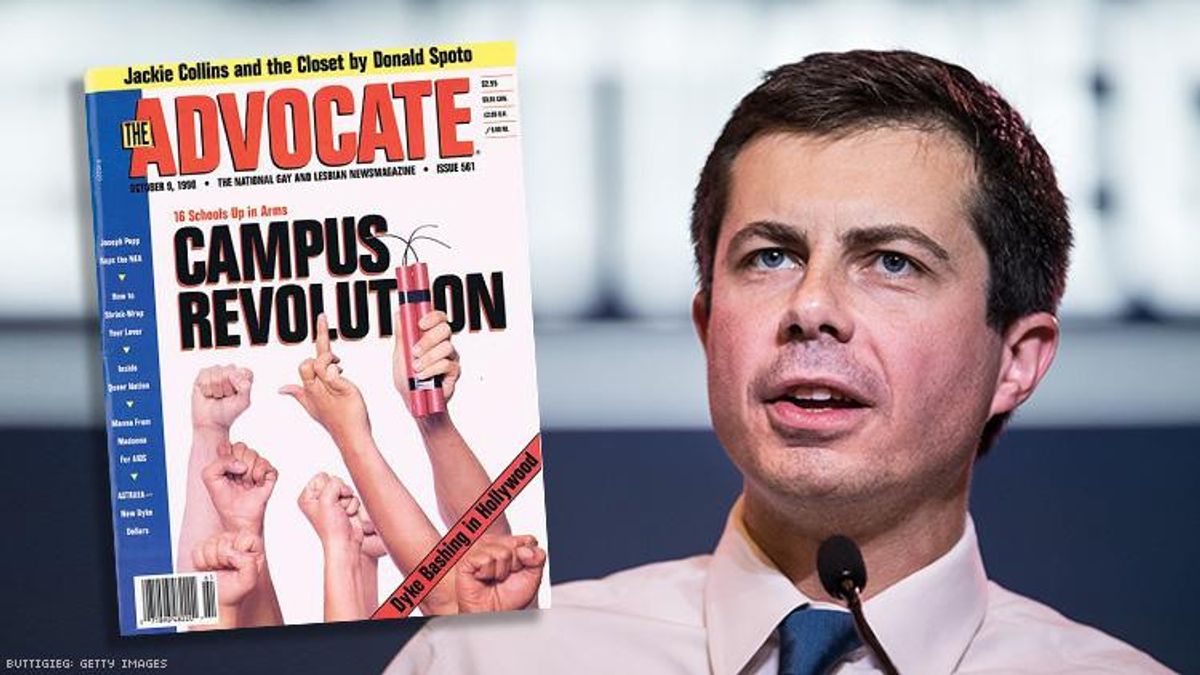

Along with all the other thousands of people who came before Mayor Pete, including the hundreds of us who have worked in LGBTQ media over the past seven decades since Edith Eyde (under the pen name Lisa Ben) published Vice Versa, the first North American lesbian publication in 1947. As the editorial director of the country's oldest LGBTQ magazine (The Advocate celebrated its 52nd anniversary this year) and someone in this field for 30 years, I know how hard it was for LGBTQ media outlets and the people who worked at them, especially in the years before the internet when we were often the sole voice reaching out to queer folks in many places.

Historically, police didn't just raid our bars, they raided our media. In 1969, police raided a New York City bookstore and removed 15,000 homoerotic magazines and films -- and not a single mainstream newspaper or media outlet reported on it. GAY, a weekly regional newspaper, did cover it and featured one of the bookstore workers, wearing little else but a smile, on the front page. It was, wrote Roger Streitmatter, author of Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America, a way for the editors to "inform and amuse its readers while thumbing its nose at journalistic convention."

It typified the LGBTQ press back then, he argued, which was, "Brash. Bold. Audacious. In-your-face. Defying the rules of Amerian journalism -- and proudly so."

The men who founded ONE, the first gay magazine, in 1953 (Dale Jennings, Tony Reyes, Martin Block, Merton Bird, W. Dorr Legg, Don Slater, Chuck Rowland, Harry Hay, and Dorr Legg) and the women behind The Ladder, the first nationally-distributed lesbian magazine, in 1955 (Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, among others) did so against great odds. And when the Stonewall Riots came, it gave birth to a new LGBTQ media that would have publications led by trans women, Black gay men, queer kids, and every other permutation at some point. This blossoming wasn't a moment too soon. After all, no national publications covered the Stonewall Riots, and only one NYC outlet did so. We covered it -- the LGBTQ media that is.

Do know, though, that while covering LGBTQ issues became (and still is) a calling for many of us journalists, we paid a steep price. For most of those nearly eight decades, our media has existed, we've had little support outside our community. It's lovely to see the Gap and Coach, Levis, Apple, and even Kroger lineup to support us now with advertising and parties and sponsorships, but there wasn't a national company willing to advertise until the 1980s. For at least a decade, many of us editors joked that without Absolut (one of the earliest supporters of LGBTQ publications), there would be no queer media.

Most of us started out unpaid volunteers doing this work on top of other jobs that paid the bills, just to get our issues covered and offer a lifeline to others who were more isolated than us.

Police and homophobes raided our tiny offices for years. Bigots threw our newspapers in dumpsters by the hundreds or thousands and burned our newsstand boxes through the 1990s.

Some of us were beaten in our own offices or homes simply for daring to be an LGBTQ journalist -- this because we were out at work (at a time when the mainstream didn't employ LGBTQ journalists who were out or even "suspected" of being queer) and because we dared discuss issues that mainstream publications wouldn't care about until very, very recently. (Heck, it took Elizabeth Warren saying the names of the trans people -- mostly Black women -- who have again this year been murdered in record numbers to get their names in any kind of mainstream presses.)

By 2001, there were over 2,600 LGBTQ publications in the U.S. And now, after the blossoming of glossy mags, the digital boom, and all the other queer outlets added since -- we surely have over 3,000 media outlets representing the LGBTQ community. (And it would be much more had we not a lost a record number of publications over the last few years as paper gives way to online reading.)

Streitmatter, in fact, dedicated his book to "the courageous women and men who founded the lesbian and gay press long before it was fashionable or financially profitable to do so. Those pioneers nurtured this new journalistic genre even though it meant being fired from their jobs, being shaken from sleep in the middle of the night with harassing phone calls, and having their bones crushed by baseball bats wielded by bigots who insisted that the material documented in the gay and lesbian press -- and now in this book --had to remain unspeakable."

Actually, I suggest Mayor Pete go read Unspeakable before his next interview and re-think his assumptions about the power and purpose of LGBTQ media.

I think Pete wasn't just grumpy; he was being short-sighted and forgetting that it is LGBTQ journalists (and other activists from his own community) who have helped him get where he is, who've earned him many of the rights and privileges that allow him to stand on the stages he's on now, and have helped him build an audience and fan base among young people.

We weren't palatable to mainstream America. We were radicals.

I hope that Buttigieg remembers too, that those of us who were (or are) visibly radical, flamboyant, femme, of color, nongender conforming, disabled, in-your-face, transgender, queer, polyamorous, and otherwise not the "right kind" of "gay" candidate are the very ones who helped push America to see that Pete Buttigieg could be.

Diane Anderson-Minshall is the editorial director of The Advocate. Follow her on Twitter @deliciousdiane.