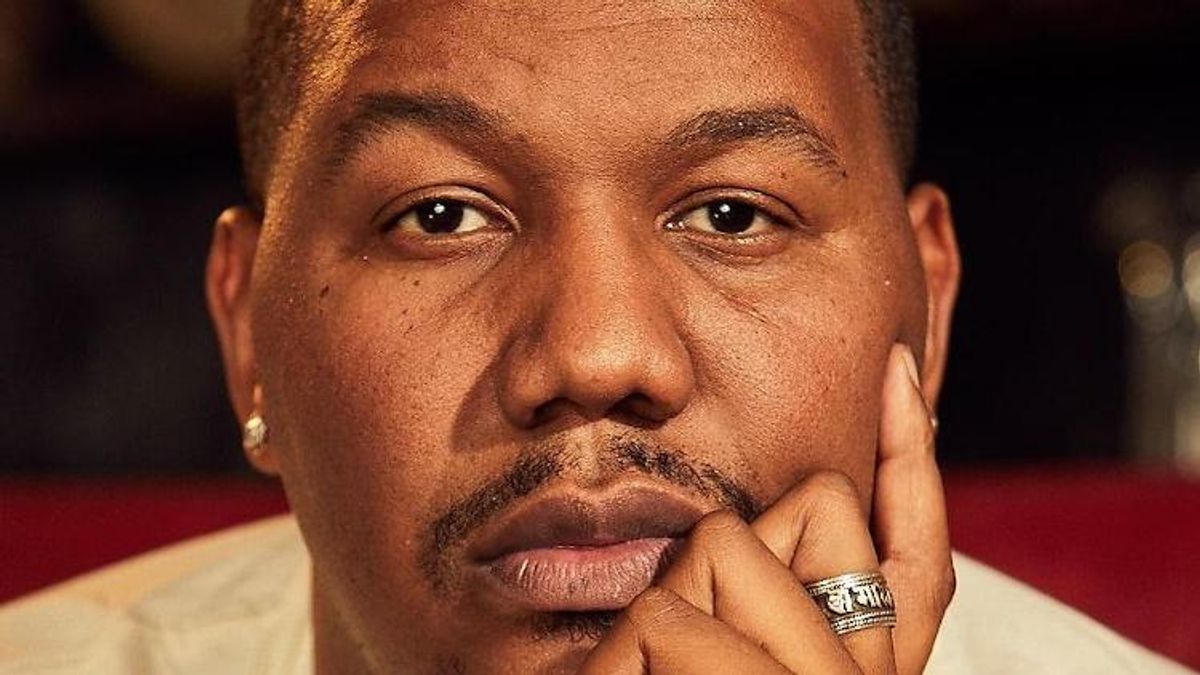

To watch the Oscar-nominated short film Two Distant Strangers on Netflix by Emmy-winning, bisexual writer and comedian Travon Free, is to come away feeling both impressed and defeated. The film is brilliantly made, which is the impressive part, yet it crystalizes what a Black man feels like each time he steps out the door, which is the disheartening part.

Without conflating its message, the film could easily be made to depict the continued murders of trans women of color, or the ongoing epidemic of mass shootings in this country.

Briefly, the movie is a "Groundhog Day" for a young Black man, who, no matter how he alters his behavior, finds himself struck down by the same white police officer. I watched it last Sunday night, and then on Monday, seemingly like clockwork, comes the news about Duante Wright being struck down, allegedly accidently, by a white police officer in Minnesota. A real-life "Groundhog Day" reminiscent of the same bloodlust that killed George Floyd nearby.

And then, on top of all this, comes the police body cam footage that shows the killing of Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old Hispanic boy, by a white police officer in Chicago. It just never seems to end.

Wright and Toledo's deaths come in the wake of yet more murders of Black trans women during the last week. Dominique Lucious, 26, was found dead in her apartment last Thursday in Springfield, Mo. "Trans women, particularly trans women of color, are disproportionately victims of violent crime," the GLO Center in Springfield, which provides services for LGBTQ+ people, said in a statement.

LGBTQ+ groups and police in Charlotte issued warnings this Thursday in the wake of two trans women of color killed this week. It just goes on and on and on.

In York County, S.C., we recently had another mass shooting in the U.S. when six people were killed. And on Friday, the day I was scheduled to speak to Free about his film, eight people were killed the night before at a FedEx facility in Indianapolis. The 45th mass shooting this year alone. There seems to be no end, and no chance to take a breath.

After each Black man is subjected to brutality by a white police officer, there are protests, and calls for criminal justice reform. What happens? Nothing.

After each trans woman is slain, or critically hurt, we write about the incident, and about them, and the need for more trans protection and hate crime bills. What happens? Just the opposite. Discrimination against trans people is the cause du jour for Republican state legislatures.

And after each mass shooting, everyone sends thoughts and prayers, or now love and prayers. What happens? Nothing meaningful, a few executive actions around the edges, calls for regulations, but in the end, more deference to the NRA.

It's a Groundhog Day over and over. All remarkably with similar incidents, similar reactions, and zero actions. How many Black men have to be wrongly murdered? How many trans women of color have to senselessly die? How many more innocent shoppers, workers, school kids, or movie watchers have to be gunned down? Why do we let it keep repeatedly happening? Are we growing callous to all the mindless violence? Have our reactions become knee-jerk, or worse, just temporary?

When I picked up the phone to talk to Free about his film, I didn't know how to congratulate him about his Oscar nod, because he's been living through the real-life horror that his film portrays. "Congratulations," I said. "But..."

"Yes, I know," Free intuitively interjected. "The film's writing, look, and execution have all received great love and acclaim, but people have been two-handed in their reactions. They are also emotionally bothered by the subject matter, which I suppose is what filmmakers are supposed to do -- elicit responses, so it's been a mixed bag for sure."

The film leaves you hanging, but not in the way that makes you think about whether the character lives or dies, like the ending of The Sopranos. I asked Free if the uncomfortable ending, for lack of a better term, was intended?

"The reality for us was to comment on a scenario and a phenomenon that keeps occurring, and not to create a false ending, but something that rings true. We couldn't think of any other way to end it. For Black men, like the character in the film, it's a daily exercise of just getting home to our dogs. We have to be resilient in the face of so much danger, endure, and hold out hope that we will overcome it."

By it, Free is referring to the constant, repeated, and unnecessary deaths of people of color at the hands of authorities. Floyd had a knee on his neck for nine minutes. Wright was killed for a traffic stop. Toledo didn't have a gun in his hands. How do you overcome these incessant murders?

"I think we can overcome them, but I don't know how long it will take," Free explained. "So many in government are resistant to the changes that need to occur. How long will we have to wait before we decide enough is enough? Eventually, hopefully, there will come a time."

We discussed how timely the release of the movie was. It dropped on Netflix last week in the midst of the Floyd murder trial, and this week's Wright and Toledo tragedies. You can't plan for something like this, but the news just seems to underscore the message of the film, that there's no escape.

"To a degree, that's probably true, and it's a testament to how many times the same thing keeps happening, and it's as if the movie is happening in real time," Free said. "As a filmmaker, we managed to make it timelier partly by making it a short film, which allowed us to not have so much time in production."

I told Free that without confusing the message of his film, he could easily develop the same story line for trans women of color and mass shootings. Did he feel the same way?

"Absolutely," he said without hesitation. "The things that are so obviously wrong and grotesque in American society, we as a county ignore or refuse to correct and that is disheartening. I have trans friends who worry so much about what might happen to them if they leave the house. It is so difficult to be a gender minority in this country, with so much of their existence being threatened. All of us are constantly playing defense, and it's really difficult to live under that weight.

"I don't know what it takes to push us toward a country that protects minorities, people of color, and transgender individuals," Free continued. "So many of our fellow citizens deem us as unnecessary and detrimental to society, so it's really left to the people who protect us."

Is there also an element of people becoming immune to all the murders, or only caring in the moment and ultimately just giving up? "You're seeing a version of this during COVID, of people just giving up. They stopped caring. There was no national cohesion around the idea of collective preservation of life, so it's turning into self-preservation.

"Society gets used to seeing all this violence happening, and it creates an environment where at first, people want to try and stop what's going on, and fix it. They want to do something about it, but only during the burst of energy in the moment. Will we be talking about Toledo and Wright in June? Probably not."

For Free, the Oscars will be bittersweet. "As filmmaker I'm excited about the nomination, but anguished over watching reality play out this week in real time. It will probably be hard to grasp the meaning of the Oscar nomination at this moment. There's the notoriety, the interviews, and dinners, occurring now, and that's one part of my life. Then there's the other of witnessing the continuation of all the violence and murders and the world we actually live in."

John Casey is editor at large for The Advocate.