It was a beautiful, sunny spring morning in 2019. I awoke to a message from my friend, Richard Vaughan, who was in Toronto and had caught the opening of a new film at the Hot Docs Film Festival the previous night.

"Hey, did you hear?" he wrote. "We just won the queer lottery: you and I are in a documentary with Fran Lebowitz!"

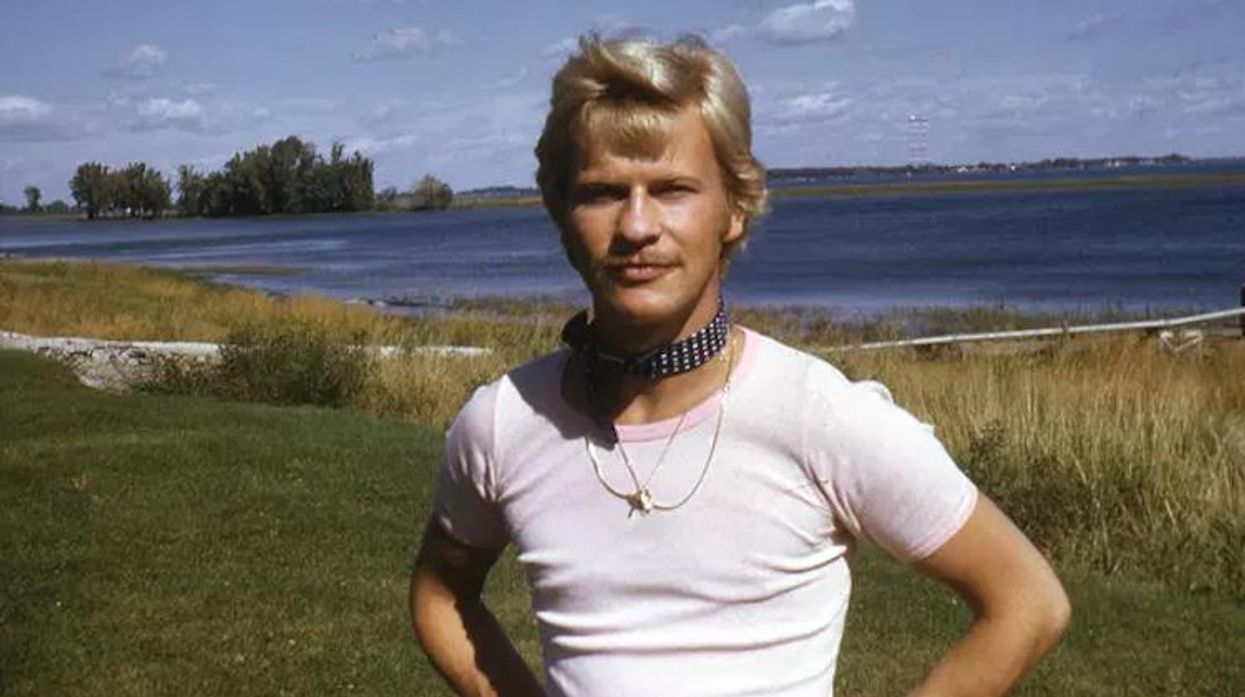

It was a typical jovial message from Richard, my friend who maintained a prolific output, writing novels, nonfiction books, reviews, poetry and plays. The film he was messaging about was Killing Patient Zero, and being involved was indeed a reason for pride. Directed by Laurie Lynd, the documentary tells the story of French-Canadian flight attendant Gaetan Dugas, who died of complications from AIDS early in the epidemic, only to later be branded as "Patient Zero." That bizarre theory attempted to explain how HIV came to North America by blaming one promiscuous gay man. Lynd meticulously traces the life of Dugas, while making his story about the larger cultural history of HIV and AIDS and how the pandemic was interpreted by the media (spoiler alert: they got much of it wrong).

As well as Lebowitz, Vaughan, and myself, Killing Patient Zero's talking heads include filmmaker John Greyson and critic and author B Ruby Rich, as well as never-before-seen archival footage of Dugas himself. The film rightly earned critical raves. It managed to correct the distorted record of Dugas (no, he was not the reason HIV came to North America) while pointing to the cruelty and vicious homophobia that was inherent in the Patient Zero mythology.

Little over a year later, I exchanged a few messages with Richard. They were the usual: we were busy complaining about how rough the freelance writing business had become. Richard was on the east coast, where he was finishing up his time being a writer in residence at a university. He said something bitchy, then something absurd. It made me laugh out loud.

The next day, I got a frantic message from a mutual friend: Richard had gone missing. No one knew where he was, and the police were searching for him. Though he had been living in a good place (a friend's basement), his university gig would soon be over, and Richard had given up his apartment in Montreal and was uncertain of what was next. The pandemic wasn't helping matters.

My worst suspicions immediately sprung to mind. Richard and I had discussed battling depression, and I knew his dark side well. We had many conversations about despair and loneliness, as well as the uphill battle of being a creative type. He was public about his demons, having written an entire book about his chronic insomnia. As a suicide risk, he was a double whammy: queer and a writer.

But another inner voice pushed back, wondering how Richard could possibly take his own life. As well as being an accomplished author and journalist, he had many friends and knew he was dearly loved. This was reflected in the huge outpouring of concern from people across Canada and around the world as people worried about his disappearance. Richard and I had discussed the issue of suicide because a year earlier a close friend of his, a popular artist who ran a Toronto gallery for a time, had taken her own life, and he was gutted by it. I spent half a day with him in Montreal after he got the news, and we wandered through the city, talking about his friend and the hole her absence left. He knew how cruel suicide is for those left behind. Why would he do this?

Within days, his body was found by police, and I would learn that he had in fact left a note, one made up of a mere four words: "Suicide notes are tacky." It was pure Richard: funny, absurd, biting. It left me in one of those surreal collisions of emotion: as I read it and reread it, I laughed and wept simultaneously.

Suicide, of course, leaves behind it a litany of agonizing questions. Richard's was no exception. I had just exchanged messages with him hours before he was reported missing. While his next steps weren't entirely clear, he did have new projects on the go. I knew that as a writer and curator Richard lived on very little money but he always managed to get by.

The jarring irony of our appearance in Killing Patient Zero was not lost on me. Richard and I had many conversations about HIV and the impact it had on our communities and our lives. Both in our 50s, we had managed to do what AIDS activists and educators were urging us to do in the darkest days of the AIDS crisis: we remained sexually active but practiced safer sex, and thus didn't seroconvert. We both had survivor's guilt and had discussed that at length too.

So Richard had survived, but not really. For many years, HIV was on our minds pretty much constantly. We were always hearing about friends who were ill or dying. We wrote about the crisis and got involved with activist organizations. The AIDS crisis never really ended, of course -- it just evolved. But that Richard would have come through all of this loss and sadness and still choose to end his life added to my despair about losing him.

If Richard Vaughan's life is to mean anything, I hope the queer community will take more time to ponder the various ways homophobia manifests itself in our daily lives. HIV remains an ongoing health issue, as does substance abuse and addiction, and depression, anxiety, and suicide (all of the above are things we experience at higher rates than the general population). It's obvious Richard was suffering. My only wish is that I could go back and convince him his life was worth living. One of his most beautiful qualities was how gentle he was with others. It was something that didn't always extend to his feelings about himself. Internalized homophobia is one of the most daunting challenges we face.

Please watch Killing Patient Zero and take in some of the wisdom of my late friend Richard. There will never be another person quite like him.

Killing Patient Zero begins streaming on Sundance Now today.

A longtime contributor to The Advocate, Matthew Hays has also contributed to The Guardian, VICE, Cineaste, The Toronto Star and The New York Times. He is Lambda-award-winning author and teaches courses in media studies at Marianopolis College and Concordia University in Montreal. He is the co-editor (with Tom Waugh) of the Queer Film Classics book series.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes