I sat on the bed in my dorm room doing what I did a lot back in the olden days of 2004: collaging -- specifically, collaging the covers of my notebooks for my classes the coming semester. January 2004 marked the beginning of my second semester of sophomore year, and everything in my life was really, really exciting.

I was the news editor of my college's newspaper and was being primed to become the editor in chief the following year. I was in love with academia, writing, activism, and performing improv every week with my best friends and boyfriend. And because I'm one of the cool kids, I was watching the State of the Union, an annual tradition of mine since age 7.

At that point, I'd lived through a Reagan, two Bushes, and a Clinton. And no matter what sort of political declarations any of those presidents would make, I've always watched the State of the Union address. When I was younger, I watched because my parents did. When I was in eighth grade, however, my fantastic history teacher, Stephen Masciangelo, taped Bill Clinton's 1998 State of the Union, and we watched it over the course of a week. He broke down exactly what everything meant -- all of the policy points, the body language, the pomp and circumstance, the fact that Clinton wasn't talking about Monica Lewinsky but instead about Saddam Hussein. After that week, I felt a sense of intellectual ownership of the event. It became a tradition for me.

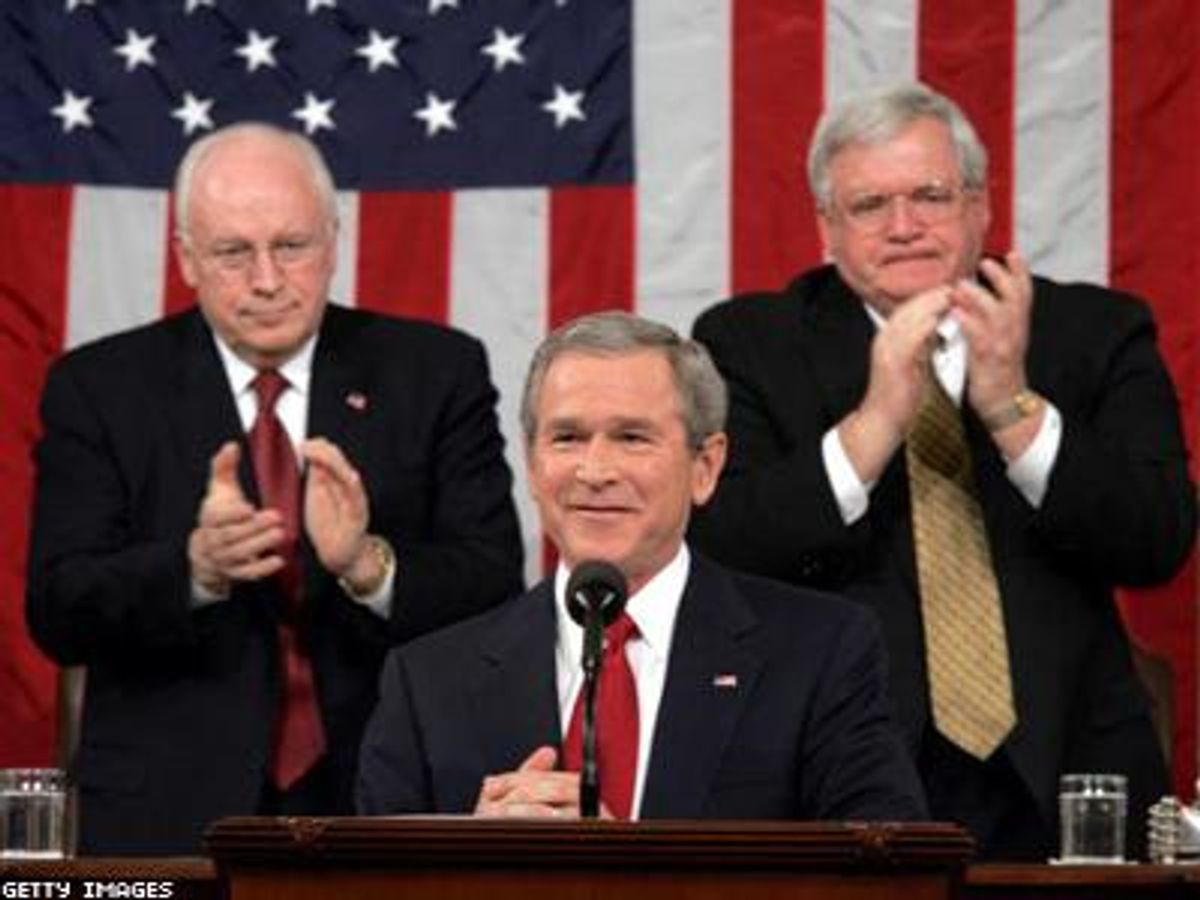

By the time this Tuesday in January 2004 rolled around, I figured I would be rolling my eyes through George W. Bush's big plans as per usual. But at some point, he started talking about gay marriage.

"A strong America must also value the institution of marriage," he says. My feminist eyeballs shift around, as I continue gluing, and he keeps talking.

"I believe we should respect individuals as we take a principled stand for one of the most fundamental, enduring institutions of our civilization," he said. "Congress has already taken a stand on this issue by passing the Defense of Marriage Act signed in 1996 by President Clinton. That statute protects marriage under federal law as a union of a man and a woman, and declares that one state may not redefine marriage for other states. Activist judges, however, have begun redefining marriage by court order without regard for the will of the people and their elected representatives. On an issue of such great consequence, the people's voice must be heard. If judges insist on forcing their arbitrary will upon the people, the only alternative left to the people would be the constitutional process. Our nation must defend the sanctity of marriage."

As a journalist who has covered this stuff for years now, I find these words so empty. The strategy and sentiment are so passe, since we're about to go coast-to-coast on marriage. But 19-year-old, not-yet-jaded, political science minor Michelle was hearing this sort of real-world homophobic hatred for the first time -- the institutional, large-scale, let's pass some laws because we have nothing else better to do sort of homophobia.

After a while, I couldn't even hear the words anymore. I had to put down my scissors and glue, because my hands would not stop shaking. My body shook. I got that adrenaline-fueled, fight-or-flight feeling. The feeling when the glands in the back of my throat start firing. My eyes welled up with tears -- not from sadness, but boiling rage. Every pissed-off thought I could ever have collided behind my rib cage all at once. I nearly walked into the hallway and shouted just to hear the echoes of my anger.

How could he do this to people? Couples who have been together for decades? Couples who love each other and have been raising children together? He was talking about people who fought our wars (under "don't ask, don't tell," no less) and taught children and perform surgeries and pay taxes and vote. He was attacking those people.

And me. This was about me.

In that little dorm room on the fourth floor of Funnelle Hall at SUNY Oswego, as George W. Bush declared that queer people's love isn't the same as everyone else's, I realized that my feelings for some female friends and teachers and teammates and coworkers and random women on the street -- those feelings were directly affected by President Bush's declarations. It stung. It felt like a sucker punch to the throat. I felt assaulted. This was the moment I realized my thoughts and feelings were not just some phase or that I'm just cool enough to admire other women. No matter how many boys I hook up with or hold hands with or date, I am not straight. Because for all those boys, there were always a fair number of girls whose hair I'd wanted to stroke or whose body I wanted to hold. There were girls I'd felt so emotionally drawn to, but could not describe why. This was not friendship, mutual respect, or general admiration (though those factors were also involved). It was attraction. And the president of the United States was telling me my innate attractions were inherently wrong.

A few days later, I turned on CNN while getting ready for class, and there was that young mayor of San Francisco, Gavin Newsom, marrying gay couples. The grin across Newsom's face showed me that he had also been pissed that previous Tuesday. I later learned he was there at Bush's State of the Union and boiling with rage along with so many of us. There were really old women clutched to each other and happy gay men getting married at City Hall.

I put down my books and watched that newscast and cried too. This time my tears were joyful, even though we all knew those marriages probably wouldn't have any legal standing. It was as though someone heard me. They heard my closeted, confused, little 19-year-old brain yearning for someone to just tell me everything was going to be OK.

MICHELLE GARCIA is the managing editor of The Advocate. Follow her on Twitter, where she'll be live-tweeting during the State of the Union @MzMichGarcia.