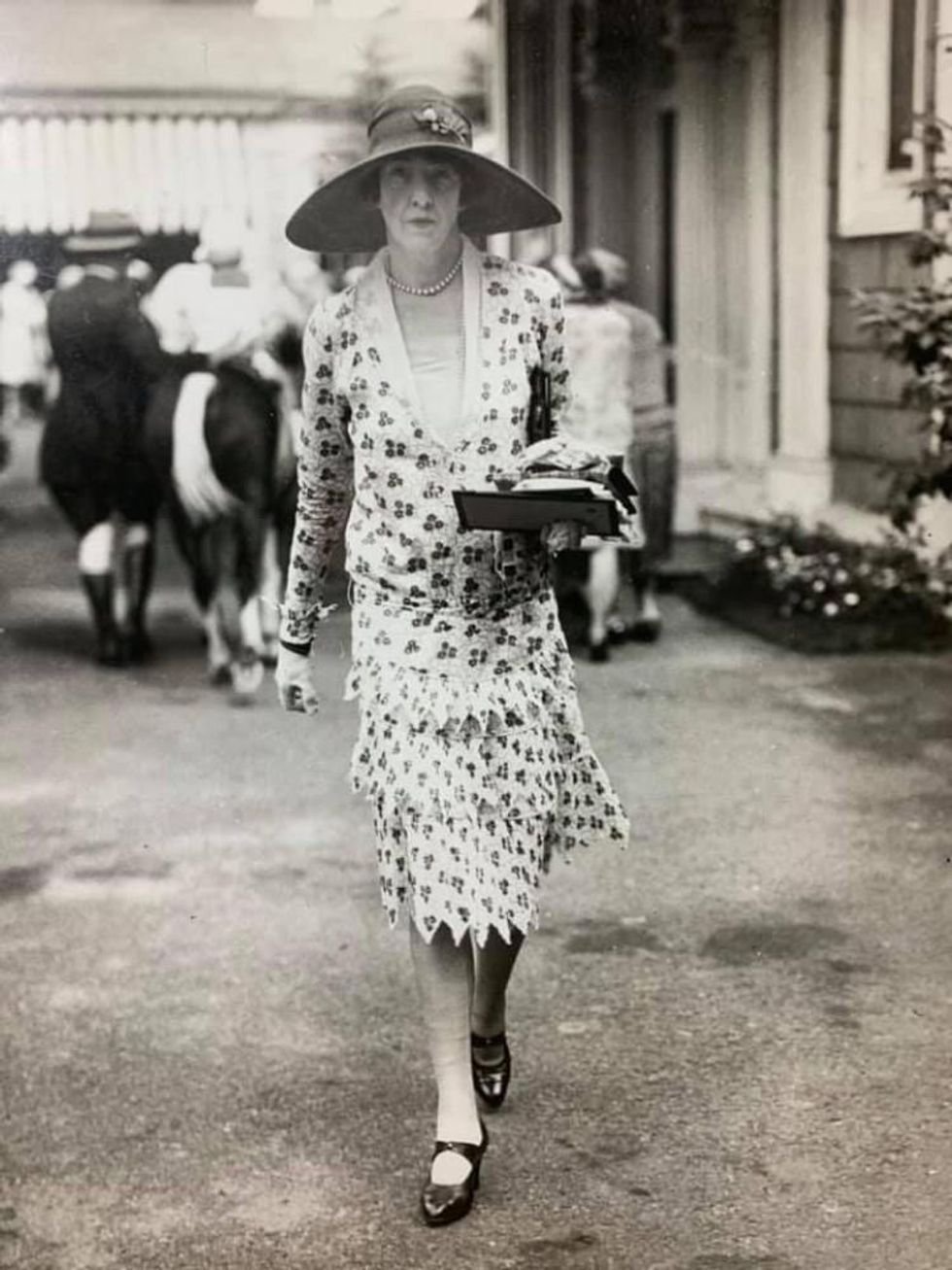

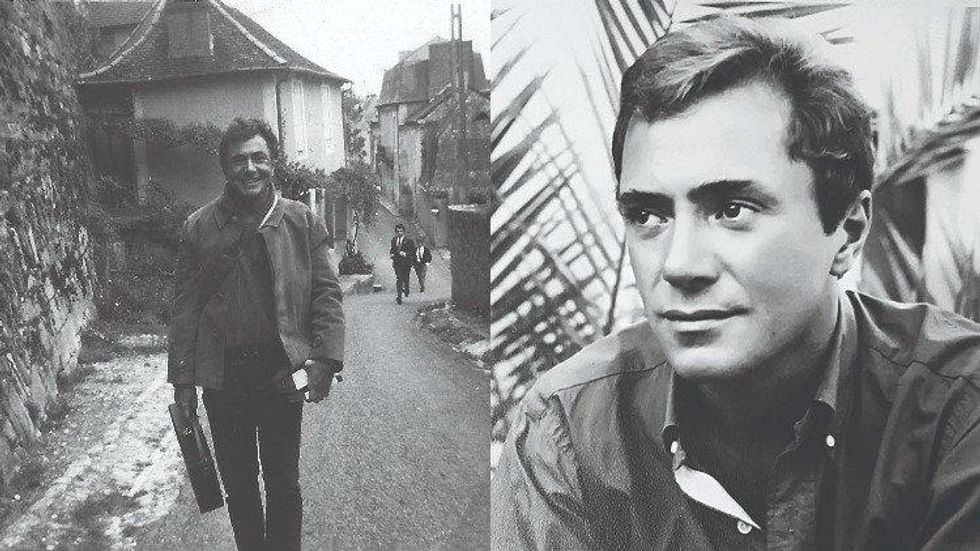

Eduardo Tirella (courtesy Peter Lance) and Doris Duke (Getty Images)

No one more than I wanted what happened at the handsome manor house at Rough Point in 1966 to be, as it has been called historically, "an unfortunate accident," and for the richest woman in America, Doris Duke, to be innocent of murdering Eduardo Tirella with intent. I've said that at least a dozen times to the 3,400 members of my Facebook page, Newport Lost and Found.

Devoted to Aquidneck Island lore and architecture, many of the page members are as riveted by this true crime case as I am. Like me, they too were heavily invested in Duke's identity as a dedicated philanthropist and preservationist who, by helping others, seemed to overcome the many negatives attendant to her fortune.

At first glance, Ms. Duke appeared to be a glamorous and attractive figure, and so did Tirella, her multitalented private decorator, confidant, and curator. Like me, he was gay and hailed from modest circumstances. Part of what Duke liked most about him was his failure to be overawed by her riches. Duke was a preservationist -- one with unconventional tastes for opulence and the extraordinary -- as am I.

Sgt. Fred Newton (lower right) on scene after Tirella's death. Photo by Ed Quigley, courtesy John Quigley

So for those of us who had given the billionairess the benefit of the doubt, the conclusion of The Newport Police Chief in 1966 that Eduardo's death was the result of "an unfortunate accident" was quite appealing.

Now, unless one is delusional, that option is impossible.

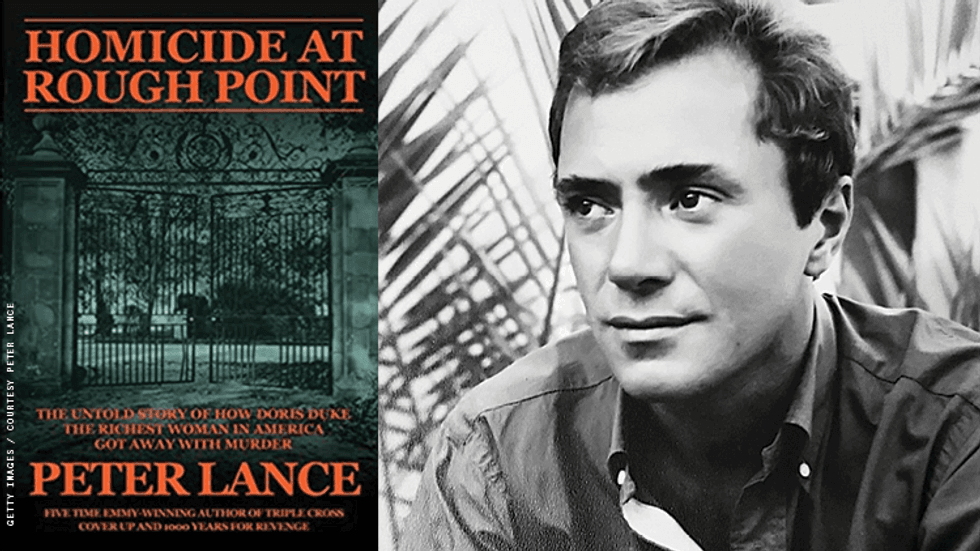

Painstakingly gleaned from the evidence compiled by forensic experts on the scene, and his exhaustive corroborative research from innumerable sources, former ABC News correspondent and author Peter Lance's new investigative book, Homicide at Rough Point, is unequivocal. There's no more reasonable doubt.

She did it.

That's why I was so disappointed in June when two esteemed institutions, The Redwood Library and Newport Historical Society, each demurred on my offer to host a public dialogue to explore his findings. The dismissive positions they took -- as if nothing had changed -- made me determined to join Peter for a discussion at a book signing he had scheduled in his former hometown, the scene of the crime.

On Bastille Day, the gathering of about 60 was held at The Brenton Hotel on the Newport waterfront. It gave me an opportunity to relate why I find Peter's work so invaluable. With what he's uncovered, it's not as if eager visitors will no longer come to see Rough Point, one of the four places where Duke lived so lavishly. Nor will The Newport Restoration Foundation or the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, which she established, cease to bestow funds for worthy causes.

Instead, like it or not, things are sure to develop much as they have at Monticello where Thomas Jefferson's legacy has been rewritten. For decades, a great effort had been made at that house museum to suppress and deny ugly truths of exploitation and rape, but they have now been recognized and embraced. Similarly, from now on, Duke's willingness to murder Eduardo, her "longtime companion" rather than let him leave her, will enhance our appreciation of who she really was.

NEW EVIDENCE COMES TO LIGHT

For my new friend Peter Lance, his rewrite of history was underscored days before I arrived in Newport, when an unassuming man came up to him unexpectedly at the hotel. That man was Bob Walker.

"I just read your book," Walker told the author. "Not only was your account of the murder 100 percent consistent with what the police sergeant who investigated concluded, but I was there. I heard the entire lead-up to the crash and I confronted Doris Duke seconds after it when she jumped out of the car and was staring down at it--in cold blood."

Eyewitness Bob Walker was delivering papers the night Duke killed Tirella at her Rough Point estate. Photo courtesy Peter Lance

On the day of the homicide, Walker said, he had been a 13-year-old paperboy, on his way to deliver Duke's copy of The Newport Daily News. Turning from Ledge Road, east toward Bellevue Avenue, he heard a series of occurrences that tracked precisely with Sgt. Fred Newton's analysis of Tirella's killing. "Seared" into his memory he said, were the sounds of "a man and woman arguing, silence, a racing engine, then a crash, moans from the man, a plea of "Noooo!," the engine's roar and a final crash after Ms. Duke drove across Bellevue, dragging Tirella underneath a station wagon, smashing down a fence, and careening into a tree.

Inquiring of an apparently uninjured Duke three times whether he should ride off to seek help, Walker, the paperboy, was met with a resounding rebuke from the 6'2" heiress, who pointed her finger at him and yelled, "Get the hell out of here!"

Why didn't Bob, now a retired steamfitter, former U.S. Marine, and father of five, not report his horrifying observation to the police? Because his father, slamming his shaken son against a wall at their home, had forbidden him from telling anyone.

Paperboy Bob Walker (third from left) with his father Bob Sr. (far right) and family 11 months before he saw Duke murder Tirella. Photo courtesy Bob Walker

Years later, his father explained that knowing "what Doris Duke was capable of," he feared that his son (a compelling witness) might have been killed -- rear-ended by a truck some day while on his paper route perhaps. Such was the perception of locals of the kind of power that Doris Duke wielded back then in Newport, R.I.

THE VALUE OF EDUARDO'S LIFE

That provoked another question in my mind. Why, in the privileged artistic circles of Hollywood, New York, and Newport where Tirella was well-known and well-liked, was his life and death so easily discounted? What made him so expendable? How could Duke so extravagantly mourn his loss, but then, bad-mouth his memory? Was it just to short-change his heirs? (Which she did). Was Eduardo's unimportance because he wasn't a blue blood, because he was Italian-American -- or simply because he was gay?

"We've always been seen as useful. So we're accepted by Newport high society, conditionally," says an LGBTQ+ activist, who, with tactful dexterity, also manages to be an insider among what's left of the old elite in The-City-By-The-Sea.

Speaking freely on condition of anonymity, he muses to me on Doris Duke's likely mindset toward Eduardo Tirella, who was supposed to be her friend -- and on the role of gay men in high society.

"As long as we remember our place -- as extra men who know how to dance, men with good clothes, fine manners, and amusing conversation; men who can be counted on to assist in shopping, planning a party, arranging flowers or emergency bartending; so long as we don't discuss gay sex or gay oppression, or our ongoing struggle for civil rights, we are much appreciated," he insists.

Recalling gay notables from yesterday's Newport, he says, "When tourists visit the grand houses associated with these queer folk, it's as if we never existed. No one talks about those who came before us, any more than they talk about how essentially slavery was connected to Newport's colonial houses or how the 'China Trade,' associated with mansions like Kingscote and Chateau-sur-Mer, amounted to forced drug dealing imposed on the Chinese."

Until his death in 1905, one of Newport's past gay greats from the 1880s was the famous party host Robert L. "Bobby' Hargous. Another was Edith Wharton's friend, architect Ogden Codman. Socially prominent, Codman was responsible for some of the resort area's most elegant houses and interiors. Like his fellow gay Newport and New York designer, Whitney Warren, or Harry Leher, whose role seems to have been keeping everyone entertained, Codman took the precaution of getting married to avoid rumors and the threat of scandal.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 1928. Photo courtesy Michael Henry Adams

So did the LGBTQ+ Vanderbilts: George Washington Vanderbilt and his niece and nephew: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, an accomplished sculptress, who founded the Whitney Museum, and Harold Stirling "Mike" Vanderbilt, who invented contract bridge, and, as Peter Lance points out in his book, three times successfully defended The America's Cup. Losing a proxy battle for the New York Central Railroad in the 1950s, Mike Vanderbilt was the last of his family to be active in the business that had launched their fortune.

William S. Moore (left) and Harold Stirling "Mike" Vanderbilt, 1905. Photo courtesy Michael Henry Adams

Since the 1950s when Eduardo Tirella first arrived in Newport, a less Byzantine queer community has evolved. Certainly, today, if so esteemed, accomplished, out, and proud a gay role model was slain, his assailant, no matter how rich they were, would not go uncharged.

"Even in Newport, it's unlikely today that a Doris Duke would be able to buy their way out of being held accountable," says my informant.

GAY LIBERATION IN NEWPORT

As the decades have passed, it's been incremental. Conspicuous personalities no longer need to hide. In the '60s and '70s, society portrait painter Richard Banks, who painted Rose Kennedy and Noreen Drexel, was just as renowned as a great host. Invitations to his parties, in a wonderful house that he'd created from an old Carpenter Gothic church, were highly sought after.

In 1994, Senator Claiborne Pell gave a speech announcing what queer New Englanders already knew, that his activist daughter, Julia Lorillard Wampage Pell, who died in 2006, was a lesbian. Still, it's rather ironic that in a place where murdering someone gay could go unnoticed and barely examined, that being gay is still regarded, by some, as a liability.

Eduardo Tirella not long before his death (left) and when he was younger. Photos courtesy Peter Lance

Key to changing that attitude is the bravery of those willing to come forward to tell the truth and make a difference. One of the factors, Bob Walker told Lance, that caused him to correct the record after nearly 55 years, was his belief that Eduardo's death "was the sensational murder of a wonderful person who was wrongly taken from the earth." The full truth behind it, he insisted, "Needs to be told."

The courage he has shown by going to the police even before he approached the author, makes Walker one in a billion. The response from the Newport Police Department has been encouraging. The department's old case detective Jacque Wuest issued a very positive statement that she has formally opened an investigation into Bob Walker's revelations and will continue to pursue the case in order "to bring justice to Eduardo and his family."

Doris Duke died in 1993 and long ago escaped criminal liability. Perhaps now is the time to correct the historical record about what was clearly never an unfortunate accident?

In this video, Bob Walker discusses the events he witnessed and his confrontation with Doris Duke that fateful night. Courtesy Peter Lance

You can read Peter Lance's article on the new eyewitness, Bob Walker, and his disturbing confrontation with Doris Duke just moments after she killed Eduardo Tirella, at Vanity Fair.

You can purchase a copy of Peter Lance's book, Homicide at Rough Point: The Untold Story of How Doris Duke The Richest Woman in America Got Away With Murder at Amazon.com. You can read an excerpt from the book here.

About the author: Michael Henry Adams is an architectural, social, and cultural historian, as well as a preservation activist known primarily for his passionate work in Harlem. His commentary and analysis has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian and Out.com. He was a principal source in "P.S. Burn This Letter Please," the documentary which premiered at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival, and he's currently at work on the forthcoming book, Homo Harlem, A Chronicle of Lesbian and Gay Life In the African American Cultural Capital 1915-1995.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes