For decades, transgender Americans have lived under a constant threat of violence. Whether at their homes, places of work or in public, there seemingly is nowhere out of reach from hate.

In the last 20 years, hate crimes against LGBTQ+ people of all types have risen at historic rates across the country. And since 2016, Los Angeles -- the nation's second-biggest city has seen a startling rise in violence motivated by hate against its transgender residents, though it is ranked as one of most friendly to queer and trans people in the U.S.

The Advocate compiled data from the years 2003-2022. A primary source was the LA County Commission on Human Relations (LACCHR), which has tracked hate crime data in the area for 25 years.

In 2022, there were 44 recorded anti-transgender hate crimes in the county, the highest number ever on record and a 20-year high. Seventy-two percent of those crimes were violent, also reaching a two-decade high since 2003.

The Advocate compiled data from various sources to analyze hate crimes in Los Angeles County over two decades from 2003-2022, the most recent year on record. A notable spike in hate crimes with an anti-transgender bias occurred in 2016, and the count has remained elevated in the eight years since, marking a new deadly record with each consecutive year. The increase in reported hate crimes is due in part to more incidents, but also because of victims’ growing awareness of how to take action, which leads to a rising number of reports.

The rise in violence against LGBTQ Angelenos should be a public health emergency, experts and victims say. But various challenges to reporting and prosecuting the crimes means few sufferers achieve justice and even fewer assailants are caught, allowing them to attack again.

Equality CT

Equality CT

Advocates, community members and experts all agree that the nation’s shifting political climate is to blame. Designating the epidemic of hate crimes against LGBTQ+ people in LA and nationwide as a public health emergency could motivate governments to dedicate valuable resources to bolster a system that is overburdened at best, and outright ineffective at worst when it comes to receiving, reporting, and prosecuting hate crimes.

“Our bodies have become a battleground of politics, [which is] why we need a national state of emergency for trans people,” said Carla Ibarra, a community affairs advocate and LGBTQIA+ Liason for the city of Los Angeles’ civil rights department. “Congress, who was supposed to be legislating policies that should be there to protect us minority communities, instead is the very Congress that’s out every day trying to argue why 200-plus anti-queer, anti-trans legislations are valid.”

What is a hate crime?

While definitions vary slightly by jurisdiction, the general consensus is: A hate crime is a criminal offense that someone commits because of a motivational bias against someone’s disability, ethnicity, gender or gender identity, race, religion or sexual orientation.

ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images

ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement groups note this includes cases of mistaken identity when the victim is wrongfully identified as part of a specific group even though they are not. One recent example of this was the August 2023 murder of Laura Ann Carleton, a store owner who was fatally shot in San Bernardino County after a confrontation with a man who ripped one of her pride flags down and yelled homophobic slurs at her. Carleton was not a member of the LGBTQ community. But her death speaks to the pervasiveness of hate violence – those who are so severely motivated by animosity for another group that they’ll stop at nothing to act on that violence, even if it means targeting the wrong victim.

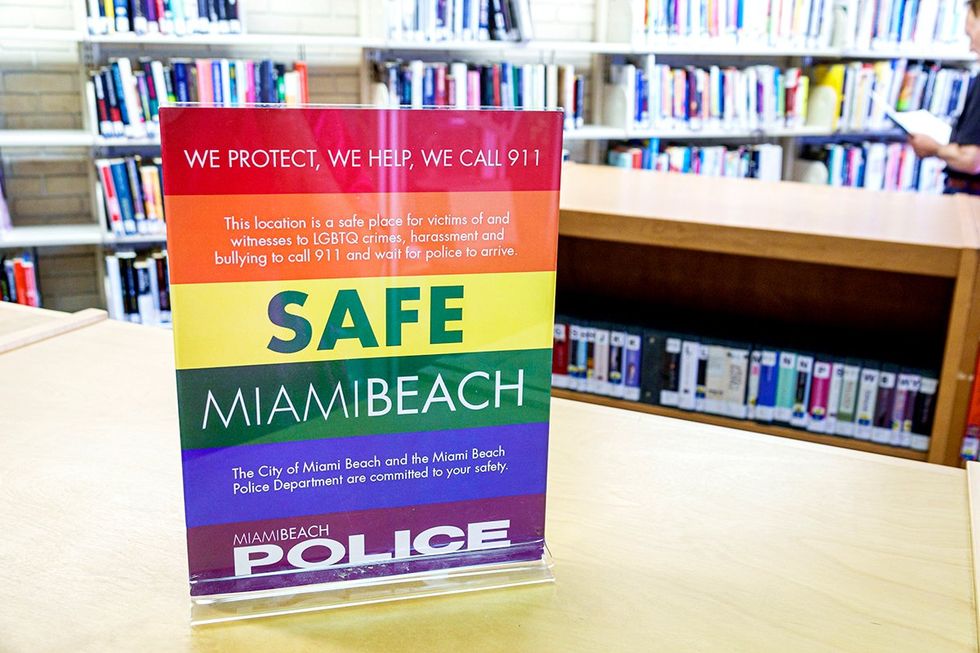

Who can receive a hate crime report?

Any law enforcement agency can take a hate crime report, but there’s many other places that do as well.

The LACCHR’s data consists of reports derived from over 100 different reporting agencies, Executive Director Robin Toma told The Advocate.

These include the LAPD and LA County Sheriff’s office, the Los Angeles Unified School District, local colleges and universities as well as nonprofits like the LA LGBT Center, Toma said. The goal of the LA County CHR is to establish a “community-based system to receive and assist people who report any act of hate,” Toma said.

Jeff Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Jeff Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Once a victim contacts their local police or sheriff to report the crime, the agency is obligated to report that to the FBI. The FBI has been obtaining crime statistics from state and local law enforcement since 1930 but only began requiring hate crime data in 1990 following Congress’ passing of the Hate Crime Statistics Act, meaning there’s limited historical context to this data.

But the numbers are only part of the story, Ibarra said.

“Do we need these numbers? In a perfect world, we shouldn't even be talking about, ‘you should protect us because this is X number of trans people are being harmed or killed violently,’” Ibarra said. “But you can’t just get any funding for any services if you don’t have that number.”

The role of violence

Hate crimes are often violent, but not always.

Law enforcement distinguishes between the two, but nonviolent hate crimes are still hate crimes if there’s sufficient bias against the victim’s identity. Murder, attempted murder, rape or sexual assault, robbery and simple and aggravated assaults are violent crimes.

Disorderly conduct, intimidation, threatening phone calls or vandalism are often considered non-violent.

Of all 2,833 hate crimes recorded by the LACCHR from 2003 to 2022, nearly half were simple assaults. In 2022 alone, 72% of hate crimes were violent, indicating what experts mark as an alarming trend of growing violence.

Scott Varley/Digital First Media/Torrance Daily Breeze via Getty Images

Scott Varley/Digital First Media/Torrance Daily Breeze via Getty Images

Toma has worked at the LACCHR since 1995 and said the rising rate of hate crimes against LGBTQ Angelenos should “absolutely” be a public health emergency. He added that anti-Black, anti-Latino, anti-LGBT and anti-Jewish hate crimes are the four largest categories and typically make up about 80% of all reported.

“The LGBT community has long been one of the largest targets of hate in LA County and we’ve documented that,” Toma said. “When we started to really focus on anti-trans hate crime, we saw that even though the numbers might not be as large, the level of violence was always one of the highest of any targeted groups.”

If you or someone you know was a victim of a hate crime, you can report it to your state or local police, or anonymously to the FBI. Or reach the U.S. Justice Department resource center for hate crime victims at 1-855-484-2846.

Editor's note: This story is one in a series for The Advocate investigating the public health impact hate crimes have on LGBTQ+ residents of Los Angeles and the country. It was produced in part by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s data fellowship program, which provided training and funding.

Equality CT

Equality CT ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images

ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images Jeff Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Jeff Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Scott Varley/Digital First Media/Torrance Daily Breeze via Getty Images

Scott Varley/Digital First Media/Torrance Daily Breeze via Getty Images

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes