Crime

LGBTQ+ Cold Case Files: What Really Happened to Marsha P. Johnson?

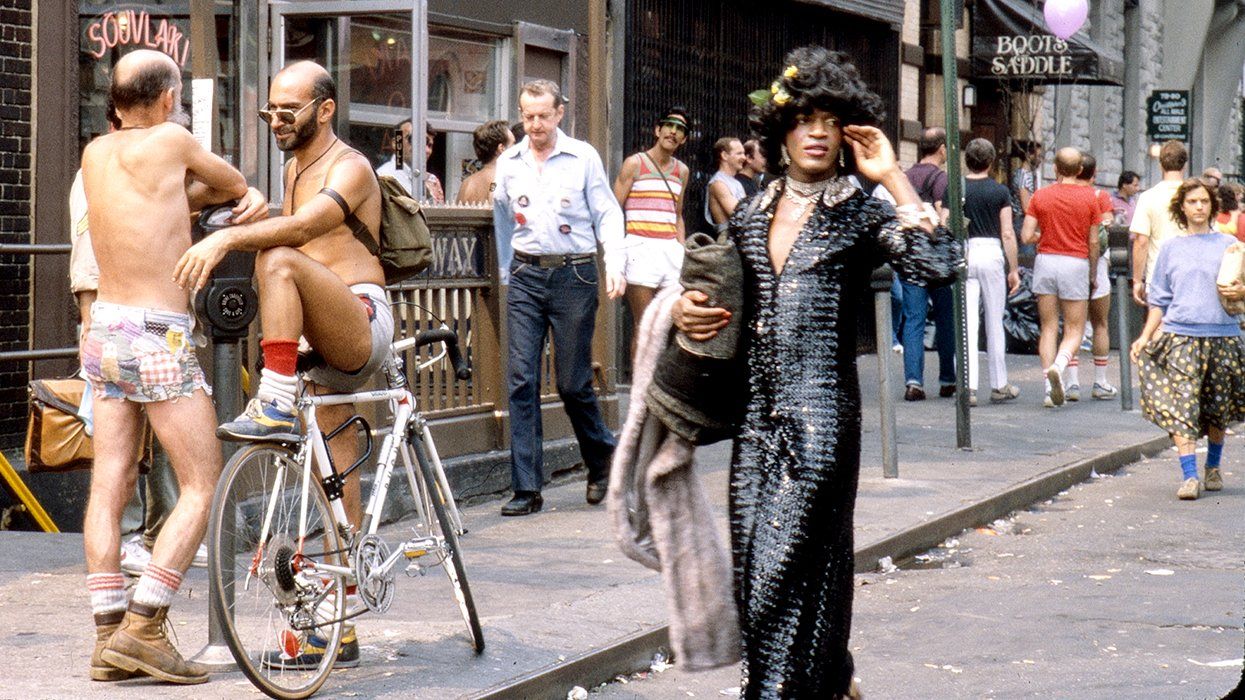

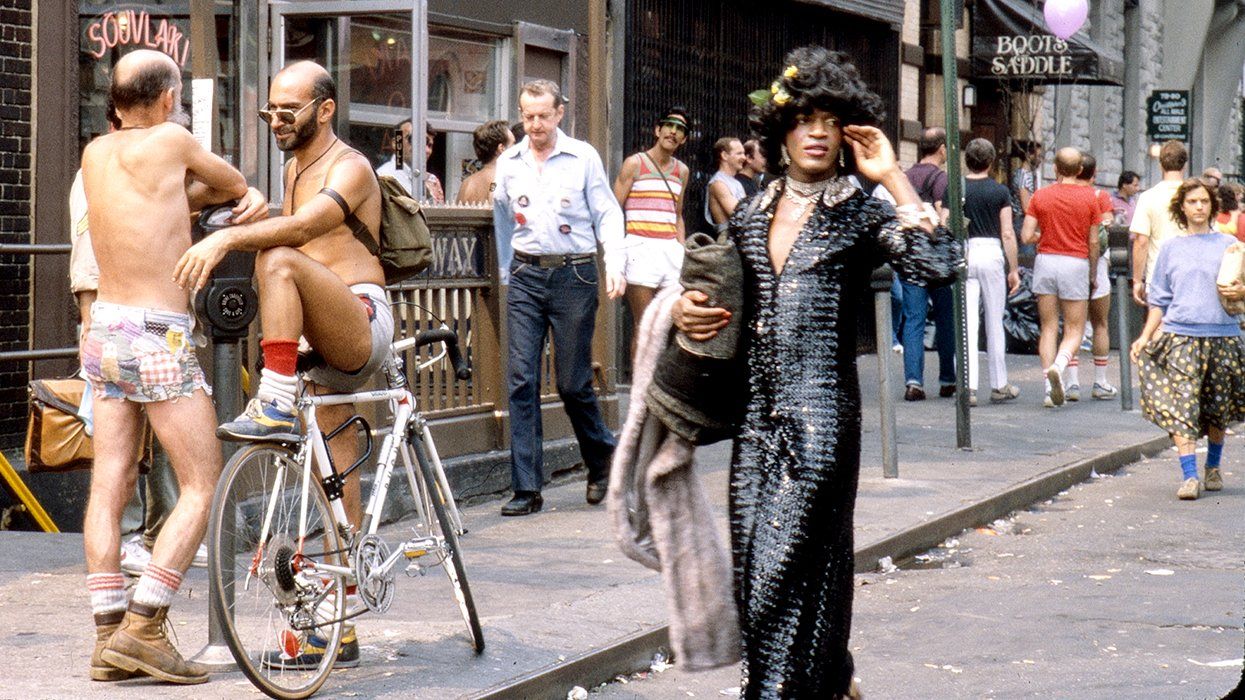

Image: Barbara Alper/Getty Images

More than three decades after her murder, Johnson’s case remains unsolved.

November 17 2023 9:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

More than three decades after her murder, Johnson’s case remains unsolved.

Editor's Note: This story is part of our series, Unsolved, Retold: The LGBTQ+ Cold Case Files, which investigates unsolved murders of queer people across the U.S. Find out more about the series.

Activist and drag queen Marsha P. Johnson might be one of the most often discussed and well-known LGBTQ+ rights activists of the 20th century, but more than three decades after her body was dredged from the Hudson River, there are still no leads on how her life was cut short.

At the time of her death, Johnson was 46 years old. She disappeared on July 4, 1992, and her body was pulled from the river two days later.

According to eyewitness accounts collected by Johnson’s friend, roommate and gay activist Randolfe Wicker at the time, her fully clothed body had a hole in her head and “laid on the sidewalk for several hours… before the coroner’s van arrived.”

Other accounts collected in video interviews by Wicker corroborate this, noting that Johnson’s head wound was in the back of her head, making it an unlikely suicide injury.

Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on Aug. 24, 1945, Johnson changed her name around age 17 when she left home for New York City. Initially finding work as a waitress, Johnson also became a sex worker, gay liberation fighter at Stonewall, and eventually a muse to Andy Warhol. She became a fixture in New York’s drag ball scene and told an interviewer in 1992, “I was no one, nobody, from Nowheresville, until I became a drag queen.”

Over the years Johnson became both a fixture in her local drag community and a beacon for struggling trans people in New York City. She established STAR House, a shelter for homeless LGBTQ+ children, in 1970 with her close confidant and activist Sylvia Rivera. Johnson was also an active member of the Gay Liberation Front, GLF Drag Queen Caucus and, most famously, present at the riots following the police raid on the Mafia-run Stonewall Inn in June 1969. Following an HIV-positive diagnosis, Johnson also dedicated time to AIDS activism and joined ACT UP.

She was also partly responsible for drag queens becoming a fixture at pride events – after they were banned from the New York City pride parade in 1973, she marched ahead of it anyway, famously proclaiming, “darling, I want my gay rights now!”

Many years after Johnson’s murder, people close to the community continue to share their perspectives on the crime and question the official record of events of the night of July 4, when she disappeared after being last seen by the Hudson River pier.

Johnson’s death was initially ruled a suicide by the New York Police Department, though within the gay and trans community it’s widely been accepted she was murdered. Many of Johnson’s friends, including Rivera, attested Johnson wasn’t suicidal at the time of her death. Randolfe Wicker at one point theorized that Johnson may have been on drugs and hallucinating and fallen into the river on accident — or, jumped into the river to escape people harassing her.

Randolfe Wicker interviewed members of the Christopher Street LGBTQ+ community shortly after Johnson’s death, as part of his video project titled “People’s Memorial.” Wicker noted a few people came forward to say they’d seen Johnson in a confrontation with “thugs” who were known to rob people in the area. One was community member Bennie Toney, whose interview footage is preserved by the Digital Transgender Archive.

Five years after Johnson’s murder in 1997, Toney told Wicker on camera about what he saw the evening of July 4, 1992 when Johnson disappeared.

Toney explained to Wicker he saw Johnson arguing with a neighbor with facial scars known as Michael, and that Michael hurled homophobic slurs at Johnson. Toney added that Michael – who he described as having a “quick temper” – pushed Johnson and “seemed like he wanted to attack her.” Toney also said this same man was later allegedly heard in a bar bragging that “he had killed a drag queen named Marsha.”

Toney also told Wicker in interviews for the People’s Memorial that “the next day, I heard that Marsha had been drowned, and the first thing that came to my mind was this guy Michael.” Toney told Wicker that he went to the police to report this suspect, but claims the New York Police Department didn’t follow up on the lead.

There’s also been speculation that Johnson could have been murdered by the New York Police Department. Around the time of her death, there was a marked rise in violence against LGBTQ+ people in New York, often either by police or perpetrators who too easily slunk back into the shadows.

In the 2021 Netflix documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson directed by David France, former Anti-Violence Project director Matt Foreman said “anti-LGBT violence was at a peak. That year we had 1,300 reports of bias crime. ... and 18% of those were based on violence perpetrated by police... It was an unrelenting wave of attacks.”

Many of these crimes, though, went unsolved. Johnson’s activism was focused on stopping street violence and advocating for victim justice. She reportedly was aware of the risks of this work, and told Wicker that his work investigating assaults by dirty cops “could get you murdered” shortly before she passed.

In another documentary called Pay It No Mind, released in 2012, co-director Michael Kasino noted, “people emphatically believe Marsha was murdered.”

The ongoing questions about the mysterious circumstances of Johnson’s death and the subsequent investigation prompted some changes from officials in New York City.

In 2002, the NYPD changed Johnson’s official cause of death to “undetermined” instead of “suicide,” at last citing a lack of evidence that Johnson took her own life. Transgender activist Mariah Lopez began calling for the case to be reopened in 2012. But since the case was never closed, the Manhattan City District Attorney’s office didn’t have to reopen it – and Johnson’s murder remains an open homicide investigation.

“In Manhattan, cold cases are not forgotten cases,” Manhattan District Attorney spokesperson Emily Tuttle told The Advocate via email. “In line with D.A. [Alvin] Bragg’s commitment to connecting with grieving families, the Office has been in touch with members of the Johnson family, and will always review any new evidence presented to us.”

That said, Tuttle declined to comment on whether the Manhattan D.A. recently received any new evidence in the case. As of 2023, Johnson’s alleged murder remains unsolved.

Have a tip about this case to share with law enforcement? Contact the New York Police Department at 800-577-TIPS or the Manhattan District Attorney office’s Cold Case Project team at 212.335.3536.

Do you have information or know of a cold case we should profile next? Reach out to Samson Amore at crime@equalpride.com.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes