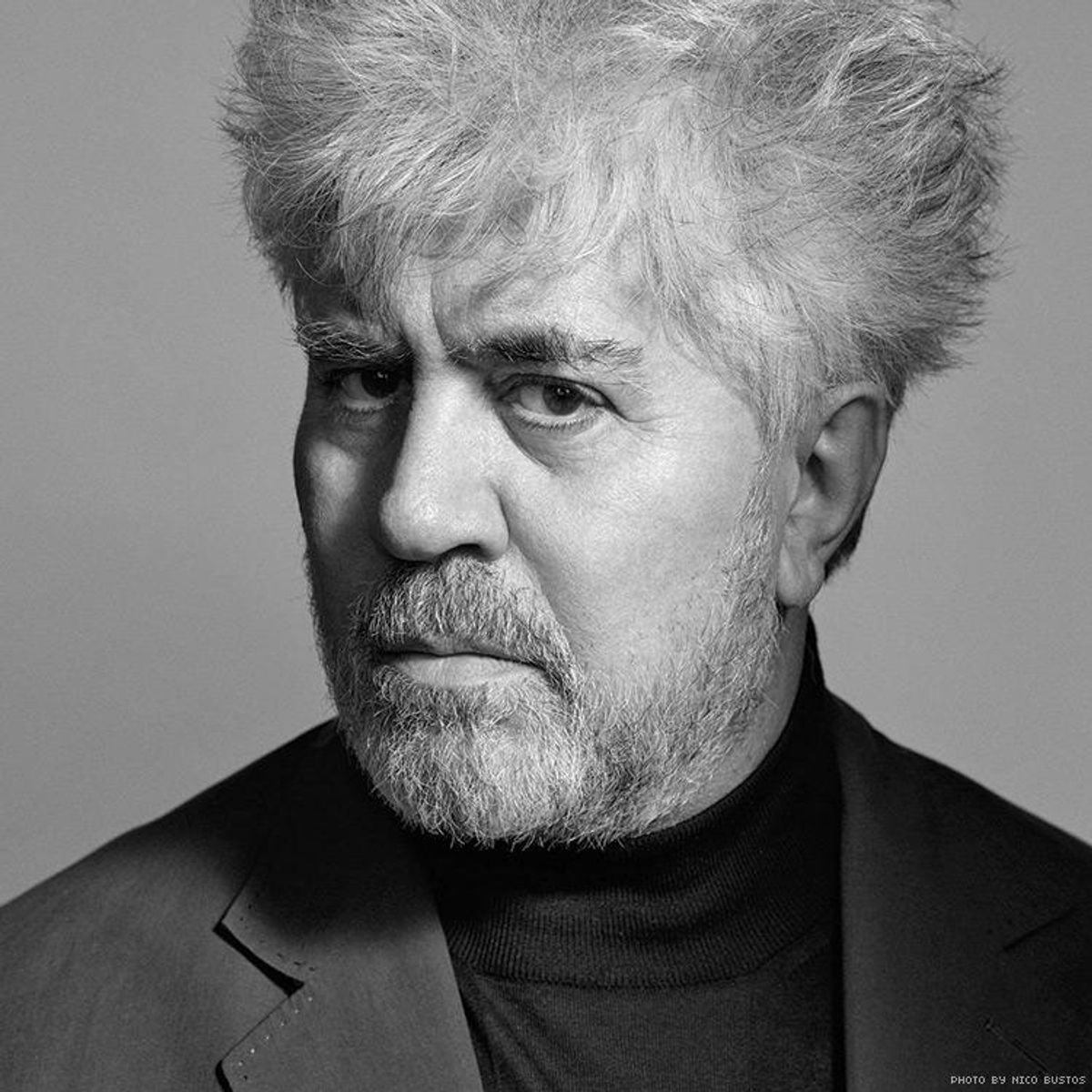

Has Pedro Almodovar, the onetime enfant terrible of Spanish cinema, abandoned the outrageousness of his youth? When I visited with the 67-year-old filmmaker in his New York hotel suite in early October, he admitted as much. "I write with the same attitude I had in the '80s and '90s, but my life is very different now. As time passes, it's natural that your storytelling evolves."

Julieta, Almodovar's 20th feature film, which opens in the United States on December 21, is a moving exploration of family relationships. Loosely based on three stories by Alice Munro, it follows a woman's life from her lonely youth through a happy marriage in her 20s, bereavement in her 30s, a perplexing abandonment in her 40s, and an effort to make sense of her life in her 50s.

Anyone familiar with Almodovar's work will recognize his trademark touches in Julieta. It is set in a female universe in which beautiful actresses portray complex, vulnerable characters -- the standouts here are Adriana Ugarte as the title character in her early years and Emma Suarez as the mature Julieta. It concerns motherhood, a subject he has returned to over and over, and it features Rossy de Palma, one of his most beloved actress-muses. Still, in many ways, Julieta is a departure. It's a drama rather than a melodrama; there are few comedic elements; and while LGBT characters aren't entirely absent, they are very much in the background. And the outrageousness that defined his earlier work is nowhere to be seen. There are no nuns with pet tigers, masochistic housewives, or laxative-popping nymphomaniacs in Julieta.

Almodovar might have embraced maturity, but he misses the wild days of his youth. "I remember in the 1980s, we would be out all night, taking drugs, and in the morning I'd go to the film set without having gone to bed. I had the physical fortitude to do that then, but I can't now. Now my life is dominated by health and work. It's a sad reality, but toward the end of your life, if you are at all interested in your work, there are things you have to give up."

He made his first films during the days of la movida Madrilena -- the hedonistic, countercultural scene that took over the Spanish capital in the early '80s during the transitional period between the 1975 death of dictator Francisco Franco and the establishment of democracy. His first two movies, Pepe, Luci, Bom (1980) and Labyrinth of Passion (1982), are fascinating documents of that social revolution; they're also narratively incoherent shockfests of sex, drugs, and punk rock.

Back then, Spain needed a shock, and Almodovar was the man to provide it. "I never tried to be scandalous," he insists. "I accept that my films were interpreted that way, but that was never my purpose. Still, it was healthy for Spain to receive this shock and to see that young people were behaving in a completely different way from 10 or 15 years earlier. For older Spaniards, this was completely outrageous, but for those of us who participated in la movida, this explosion of freedom was simply our life."

If it seems odd that more gay characters appear in those films of more than 30 years ago than in his latest creation, Almodovar says he can't force himself to address particular topics or to include specific types of characters in his work. "They appear spontaneously. When I write, I don't behave like a gay militant; I'm at the service of the story. There are times when sexuality is the theme -- like in Bad Education [2004] or Law of Desire [1987] -- and then I have to explore it. But inspiration demands absolute freedom."

Sara Jimenez (left) and Adriana Ugarte in Julieta

This seems to frustrate him. "The storytelling process is almost paranormal," he tells me. "There are certain Spanish problems that bother me a lot, that I would love to make a movie about, like historical memory. I've tried to write a script on that subject, but I'm incapable of imposing themes. Instead, the subjects come to me, and I express them. Within those subjects, usually, there are gay characters, because there are gay people in my own life and in the world we live in, but it isn't something I can impose."

Almodovar was one of the first filmmakers to include transgender characters in his work. Thirty years before the contemporary campaign to cast transgender actors in trans roles, he was making bold choices. Trans actors played trans roles, but they also played cisgender characters. In Law of Desire, for instance, trans actress Bibi Andersen, who appeared in four Almodovar movies, played a cisgender woman, while cis actress Carmen Maura was cast in a transgender role. Now, in our more trans-conscious age, Almodovar seems to have left the community behind. Is that intentional?

"I don't know," he says, applying his characteristic thoughtfulness. "In the '80s, when my movies were particularly rich in gay and transgender characters, it was something that hadn't appeared in Spanish movies before. I made a point to include these characters, because they were part of my life. I tried to treat them with the same naturalness that I would bring to a housewife or any other character. I wasn't talking about their problems, or The Transgender Problem -- I was saying that they exist and their lives are as legitimate as any other."

When I ask Almodovar if the theme of familial abandonment that recurs in Julieta is a stand-in for the kind of rejection that gay kids can still sometimes experience, he shakes his head. "No. When I was making Julieta, I was thinking about motherhood. It's an eternal subject, one I could mine forever." But isn't there a gay dimension to his motherhood obsession--even if the stereotype of the closeness between gay men and their mothers is now discredited as Freudian nonsense?

"I left the family home when I was 17, and I wasn't a mama's boy, but my mother was a big influence on my life. Not just my mother -- all the women in the neighborhood," he says. "I suppose being gay, the masculine world, which was represented by my father, his friends, bars -- that was something I viewed with apprehension, fear even. I found comfort with women. Seeing them live their lives and solve problems, that really was my education as a person."

The classic hallmarks of an Almodovar movie -- the melodrama, the troubled divas at their center, the hypersaturated colors -- are also redolent of camp. Is he trying to capture that sensibility before it disappears as gay culture becomes more mainstream?

"We don't even have the word camp in Spain," he says. "My films represent my own tastes -- and they come from the movies I saw before I was 20. In Spanish and Latin American culture, melodrama is the most popular genre. Yes, it represents a gay sensibility, but it's also the sensibility of the majority of the population. I'm reclaiming those old genres, some of which have gone out of fashion, and giving them a contemporary point of view. But it's not because of camp sensibility--it's about my own attachment to them." In other words, it's just Pedro being Pedro.