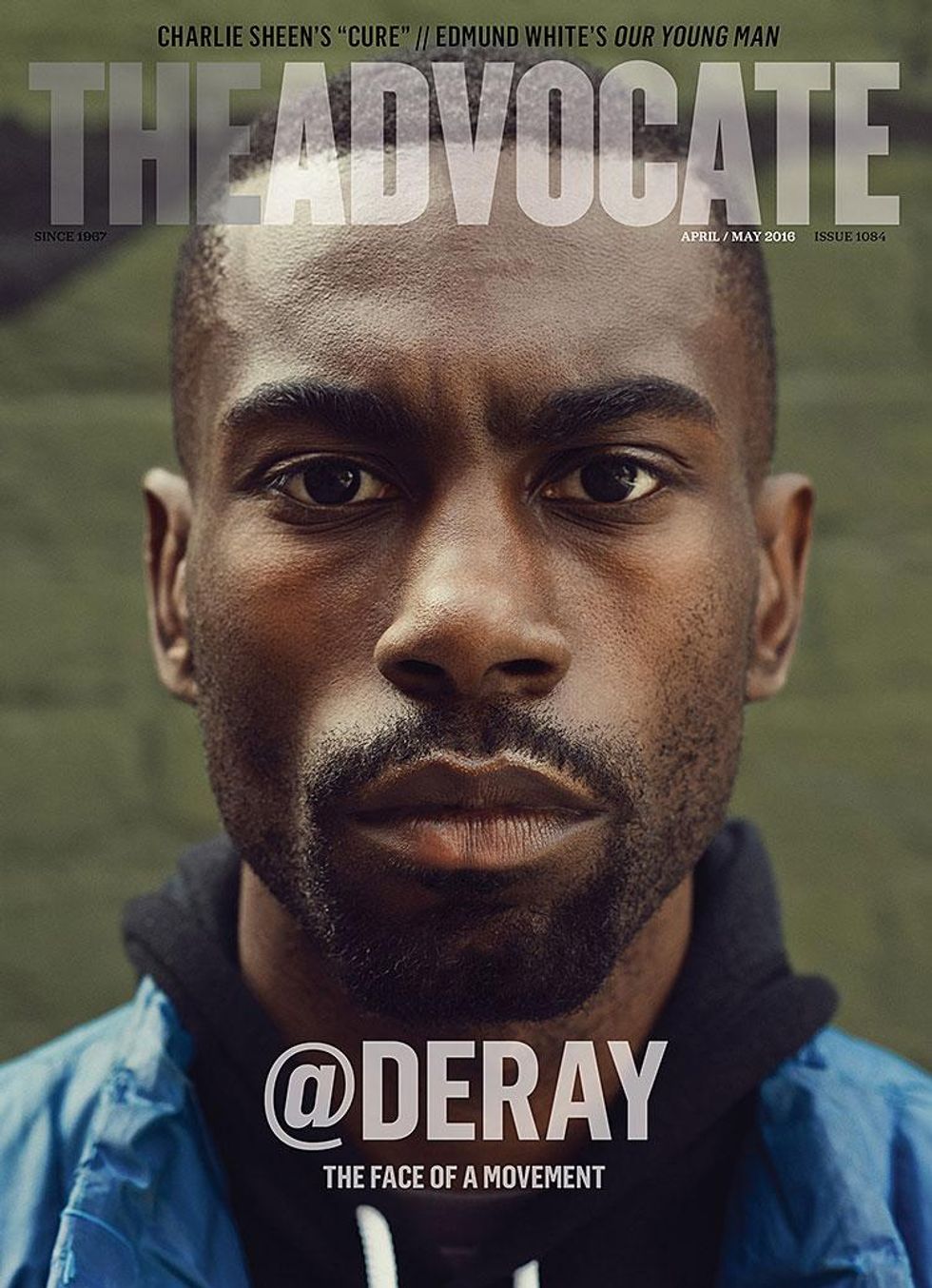

The first time I sit down with DeRay Mckesson -- the most followed activist in the Black Lives Matter movement -- I am struck by his familiarity. This feeling of knowingness is unique to my generation: millennials who've grown up not only with the Internet but on the Internet, where our online selves -- our avatars and selfies and tweets -- take the lead.

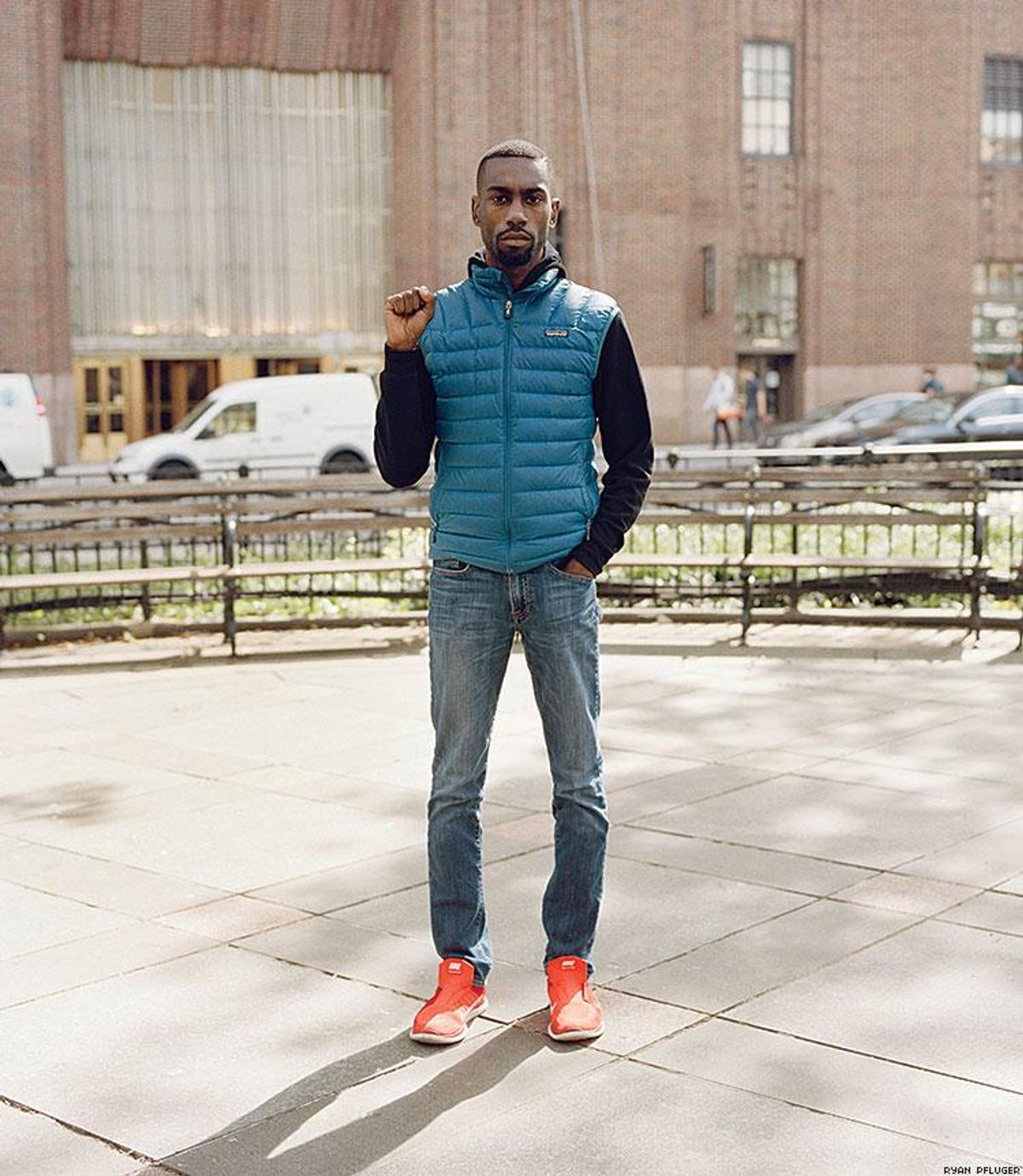

He feels familiar -- like I know he loves Spotify and uses Dove soap; I've seen his blue vest and raised fist on the streets of Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore; I've watched him respond to and block trolls. Yet he remains unknown. Consuming images he's curated for the viewing public doesn't allow us to know him, it allows us to view facets of him.

Mckesson walks into The Vine, a restaurant near New York City's Penn Station, in early January with a bright wide smile. His face is all edges -- enviable cheekbones, a sharp jaw outlined with a cutting goatee. He greets me with a hug, shakes his head, and unburdens his slight shoulders of the weight of his backpack. When he takes his seat, he exhales loudly and stares at me with eyes as vast and deep as the Atlantic. I can see in his eyes that he's assessing whether I'm someone he can let in.

"OK, I'm thrown off because I just saw a cute boy," the 30-year-old protester announces. "I wasn't expecting to see him!"

When I ask if he spoke to the cute boy, he continues, "I didn't get the chance. We were walking in opposite directions and locked eyes. It was like a damn movie! I kept telling myself, 'Look back. Look back. Now!' But I couldn't." He pauses for a bittersweet beat. "I'm not good at this stuff," he confesses, shaking his head in regret.

This missed connection is not a scenario Mckesson tweets to his 300,000 followers who look to him to fill their timelines with statistics about police violence, selfies with protesters and politicians, and unapologetic blackness. His social media presence allows his audience to feel just a scroll away from the movement.

"Twitter is half me trying to live in the world, and half me processing and sharing the world. I share a lot, and some of that is to keep me honest," he says over well-done salmon and french fries. "Twitter is the friend that is always awake. There are very few things that I don't talk about -- even my relationships. Any 'six-word story' I've written is about relationship stuff I'm working through."

The fact that he shares his love life in succinct six-word stories, inspired by Ernest Hemingway, speaks to his commitment to authenticity. Some of his six-word stories: and he mistook honesty for love; against my pride, I miss you; and I will never not love you. They read like dispatches of unrequited love.

Mckesson shows me a photo of a guy he began dating last year. He mentions that their relationship doesn't yet have a resolution. His guy mirrors him: a young trailblazer centering black folk in his work. When I ask why they aren't together, he says, "It's all in my six-word stories."

Later, I find one six-word tweet: he is afraid to be loved.

Beyond the off-again, on-again relationship, he says his love life is nonexistent. I ask the tech-savvy activist if he's on Grindr, Jack'd, or Tinder, and he throws me a fierce look.

"Could you imagine what would happen if the people saw me on there?" he says.

He often mentions the people and the movement. They have been his central audience and core concern since August 9, 2014, when unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown was fatally shot by Darren Wilson, a white police officer, in Ferguson, Mo.

Watching the Ferguson uprising unfold on television and Twitter from his apartment in Minneapolis, where he made $110,000 as the senior director of human capital for the public school district, Mckesson noticed a discrepancy between what mainstream media were reporting (riots and looting) and what he was witnessing directly from protesters on social media (a threatening, militarized police force). Their firsthand tweets, images, and videos pushed him to take a nine-hour drive to St. Louis to witness for himself what was happening.

"En route to Ferguson," he tweeted to his 900 or so followers, just a week after Brown's slain body was left in the street for four hours.

The next night, Mckesson was tear-gassed while protesting in Ferguson. Committed to documenting the uprising on the ground, he turned the camera on himself, tweeting a photo of his tear-streaked face. "Tear gas feels like extreme peppermint tingling," he shared.

A few days later, Mckesson would meet the woman whose name, from then on, would be linked with his own: Johnetta (Netta for short) Elzie, a St. Louis native who was a primary voice and trusted source from day one. The 26-year-old activist tells me over the phone that seeing Brown's blood on the same streets she visited in her youth became her call to protest.

"It is no coincidence that DeRay is my partner," she tells me. "He has become my best friend."

Elzie first met Mckesson at a street medic training to learn how to best respond to tear gas. "He was quiet and didn't know anybody," Elzie says. A few days later, she sat next to him in a St. Louis church. When the Rev. Starsky Wilson told the congregation to greet and hug their neighbor, she was apprehensive.

"I don't like touching people I do not know, but something about DeRay told me to just give this boy a hug," she said. "So I did, and I knew that I could trust this guy who is out here all the damn time."

Elzie and Mckesson soon collaborated on a newsletter called This Is the Movement, which kept activists, allies, and the media up to date on the latest in Ferguson.

"I remember when Trayvon Martin died, there was no news, and I just didn't know what was true or not. I didn't want that to be the story of Mike Brown," Mckesson says. "I remember building the newsletter thinking, People need to know, and I hope this works. And it turned into something that worked."

This Is the Movement garnered nearly 20,000 subscribers and earned Mckesson and Elzie the 2015 Howard Zinn Freedom to Write Award. After a year of protests, they launched Campaign Zero, a "data-informed" platform coalesced around 10 points to end police violence that they developed with data scientist Samuel Sinyangwe and St. Louis native Brittany Packnett, the executive director of Teach for America St. Louis.

Campaign Zero's data-packed reports have given Mckesson rare opportunities to speak with Democratic presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders as well as key decision makers like President Obama's senior advisor Valerie Jarrett and Attorney General Loretta Lynch. "We've been blessed and lucky," Mckesson says. "It's important work and people are seeing it, but I'm sensitive too that this is not freedom."

"I love my blackness. And yours" is a tweet Mckesson repeats like a mantra, an affirmative proclamation in the face of institutional and structural racism that affects black people in America. The centering of blackness is integral to Mckesson's work and the work of the entire Black Lives Matter movement -- which includes the Black Lives Matter network established by Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi in 2013 following George Zimmerman's acquittal in the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin.

Like Cullors, Garza, and Tometi, Mckesson challenges the myth that blackness is synonymous with male, cisgender, and heterosexual. Their leadership upends the myth that the leader of the movement must be a black straight man. Mckesson's blackness stands at the intersection of racial identity and queerness in the black political movement -- like many of his forebears, from Bayard Rustin and James Baldwin to Barbara Smith and Angela Davis.

"I stand here as a proud black gay man," Mckesson said in a speech at a GLAAD event in November 2015. The speech marked the first time he spoke publicly about his sexual orientation, but Mckesson is clear that it was not a "coming out" moment.

"Expressing and loving myself is often so much more complex than 'out' affords me," Mckesson said onstage before citing a conversation he had with his father Calvin during his sophomore year about a boyfriend at Bowdoin College. "It was the first time that we ever talked about sexuality," he explained, which enabled him to stop being "in the quiet" with his father.

On the phone, Calvin, who is an operations manager for a seafood trucking company in Baltimore, says he doesn't recall that conversation with DeRay because it wasn't a big deal.

"DeRay made it sound like that was the first time we talked about his relationships," Calvin, 56, says. "I have met many of DeRay's boyfriends. He didn't call them that, but I knew, and it was never an issue."

Calvin bubbles over with enthusiasm when he talks about his son, whom he raised alongside his older sister TeRay in Baltimore with the help of his own grandmother. (DeRay's mother left when he was 3.) Calvin battled drug addiction -- he's been sober for more than 20 years -- but he says that despite his struggles, his son excelled.

Mckesson was elected or appointed as a class representative every year from the sixth grade through senior year in college at Bowdoin, where he earned the President's Award for his contributions to the prestigious Maine liberal arts college. Being in student government separated Mckesson from his peers "because I represented them," he says. "I've felt like I have always lived this public life with my peers."

After graduating with a degree in government and legal studies in 2007, Mckesson joined Teach for America -- a national program that trains recent college grads from elite schools and places them as teachers in low-income districts. He taught sixth-grade math for two years in East New York, one of Brooklyn's poorest neighborhoods, before leaving the classroom, like many Teach for America alumni, to work in human resources for city schools, first in his native Baltimore and then Minneapolis -- a job he left to commit himself to the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014.

"He was making six figures and left that with no backup plan, no family money. That's a calling," Calvin says of his son's decision. "He recognized his talent and used it to better the world."

Now, Mckesson lives with "family friends in Baltimore," while his partner in the movement, Netta Elzie, has no mailing address. Mckesson says he's been living off savings and keeps expenses down by staying with friends when he travels across the country, citing more than 20 cities and 200 protests.

But as his savings dwindle, his profile continues to rise. Days after our dinner, Mckesson makes his highest-profile television appearance, taking a seat usually reserved for pop culture personalities or politicians, not protesters, on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. When I watch Mckesson on the Late Show couch, I am reminded of James Baldwin making an American audience face the realities of racism on The Dick Cavett Show in 1968. The openly gay writer, in under a minute, passionately breaks down structural inequality plaguing black people. Mckesson is part of a lineage that cannot be ignored.

After he discusses the "racist history" of America, Mckesson, who distractingly holds an iPhone throughout the interview, swaps seats with Colbert to grill him on how he'll dismantle and use his white privilege. A week later, he appears on Comedy Central's The Daily Show, where host Trevor Noah notes Mckesson's "very nice Apple Watch," which starts at $349, and claims, "You're not oppressed then. You're having a good time."

"This Apple Watch doesn't change the legacy of racism and its impact in this country," says Mckesson, who sports his signature puffy blue Patagonia vest, which is so talked about that more than 4,000 people follow a Twitter account dedicated to its ubiquity.

"It's not bulletproof, but it totally makes me feel safe," he says of his beloved outerwear. "It's irrational, but it does."

Mckesson's choice to wear the same thing daily may be the antithesis of being fresh -- harking back to winters in snowy Maine -- but it is marketing genius. His steady image (the blue vest, the raised fist) enables him to cut through the clutter of content and allows audiences to recognize him as the messenger of the movement.

His hypervisibility, though, has been heavily criticized, by conservatives who've called him a "race baiter," and in trending topics like #GoHomeDeray. Within the movement, his male privilege has become a heated point of contention. While many challenge the myth that the movement needs a single charismatic male leader, Mckesson has built a platform that's eclipsed the women in the movement, including his protest partner Elzie. Though Elzie is from St. Louis and was protesting in Ferguson from day one, she has a third of Mckesson's Twitter followers, who include Beyonce, journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates, and filmmaker Ava DuVernay.

"I'm not going to say it's easy," Elzie says. "People say that he takes up too much space even in our partnership, and they ask, Why is he on TV and not me? Why are there so many magazine articles about DeRay and not me? And that's because the media still wants the token black man, even though he is not straight."

Elzie says she's had many conversations with Mckesson about media strategy and who would do what in their partnership (she prefers print and feels uncomfortable with live TV interviews). She also says she "checks DeRay" and "holds him accountable" -- but those tense exchanges are not for Twitter or broadcast.

"The thing that keeps me grounded in the fact that he is the most visible protester is the fact that he is the most visible protester," she says of Mckesson, who she predicts will either enter politics or return to the classroom. "I remind myself of the ugliness that comes along with being the most visible."

Indeed, he is doing just that: after this interview, the former student government leader filed to run for mayor of Baltimore, where a primary is to take place April 26. Calling himself "a son of Baltimore," Mckesson writes, "I have come to realize that the traditional pathway to politics, and the traditional politicians who follow these well-worn paths, will not lead us to the transformational change our city needs."

Mckesson struggles with what he calls "salient critiques" about his prominence. "I can't defend it," he says. "Maybe this is my defense mechanism but I know this might not last. I could get kicked out of the movement any day."

When I ask who will kick him out, he shrugs. "I don't know. I'm only a man."

But he's more than just "a man." He is the most recognizable man in the movement, one who is openly gay, who doesn't suppress his sexuality, who occupies a unique position that not even Bayard Rustin -- the chief architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, who was largely hidden by the Civil Rights movement because of his sexuality -- was able to occupy.

"I'm not ashamed to be gay. All of me gets to show up and you don't get to decide how," he says. "But I also don't feel that burden to come out. I feel the burden to do really good work. The biggest thing I can do in the movement is be a gay man doing really good work and not be afraid to love."