Before the Internet existed, feminist bookstores were my Google, my Craigslist, my OKCupid -- and, of course, my Amazon. When I moved to Madrid in 1989, my first stop was the Libreria Mujeres. Sure, I wanted something to read, but I also needed a place to live and to get the scoop on the social scene. I'd spent the previous few years working at Lammas in Washington, D.C., and I was betting that the Spanish store would have its own equivalent of the thick binders of flyers about groups, meetings, and gathering places that women came to Lammas to consult. Sure enough, although the books on its shelves were different, and it had no softball team, the Libreria Mujeres provided the connections I couldn't have found anywhere else. A few days later, I moved into an apartment I found advertised on the shop's notice board -- and that straight roommate introduced me to almost all the queer friends I made that year.

Three decades later, the bookstore scene is very different. All but a dozen or so of the more than 140 feminist bookstores that operated in the mid-1990s have closed, and only a handful of LGBT bookshops survive. Still, their legacy remains strong. In 1967, when Craig Rodwell opened New York's Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, and in 1973, when feminist book- stores had been established in at least eight cities across the United States, these locations were much more than retail establishments. They welcomed people of all ages and were free of the risk of exposure that accompanied a trip to a gay bar even into the 1970s. A feminist or queer bookstore was the first explicitly gay-friendly space many young people visited -- and for word nerds, they were nirvana. As writer Edmund White once said of Giovanni's Room, the Philadelphia institution Ed Hermance operated between 1973 and 2014, "The gay book- store is so important. It's a non-alcoholic place for cruising.... I think people who are looking for bookworms are not immediately obvious in bars."

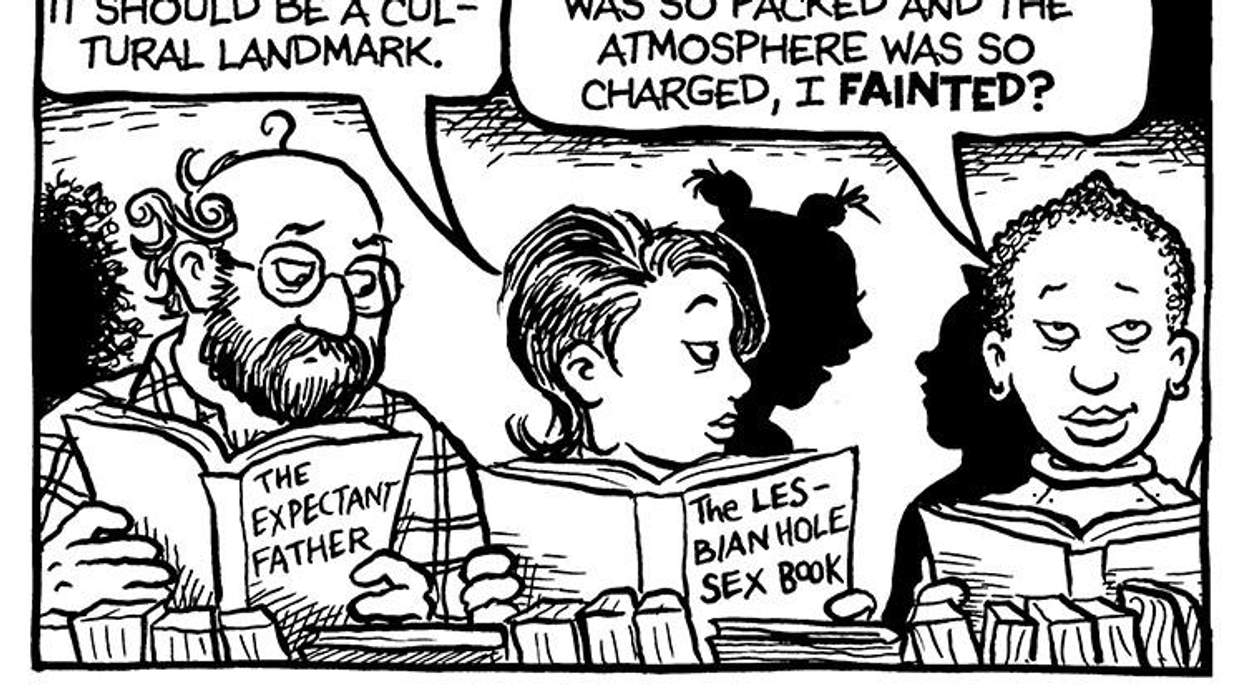

The women's and LGBT movements for civil rights were driven by injustice, but they were fueled by books. It's no coincidence that Mo, the central character in Alison Bechdel's long-running comic strip "Dykes to Watch Out For," which appeared between 1983 and 2008, spent most of those years working at Madwimmin Books. It was the perfect vantage point from which to chronicle the feminist debates of the era, which played out in books and magazines -- and to poke gentle fun at the titles everyone was talking about. In our own era, when people associate "gay culture" with movies and TV shows more than novels, and when Twitter wars have replaced the vigorous debate that often accompanied new nonfiction releases, I wonder if readers would even catch the references in the satirical book covers -- like Boots of Rubber, Isotoners of Gold -- Bechdel sprinkled throughout her strips.

In her 2016 novel A Thin Bright Line, Lucy Jane Bledsoe recounts a lightly fictionalized version of her lesbian aunt's biography, and many of the key moments in the characters' lives coincide with reading books--pulp novels, poetry collections, paradigm-shifting works of nonfiction -- that were passed from woman to woman. One 1958 lesbian constantly carries "a miniature homosexual library, always stuffed with pamphlets, newspaper clippings, and books" in her purse. Bledsoe told me she wanted to show that "books were so important to queer women of that time, the primary way information about the possibility of queer lives could be shared and learned about."

Proselytizing for feminist literature was a political cause as much as, if not more than, a business venture. Working in a bookstore provided women with essential lessons in working independently and cooperatively and forced them to face the challenges of running an explicitly feminist, anti-racist, queer- friendly workplace. As well as a source of books and music, the bookstore was a place of employment, an income stream for the craftswomen and jewelers whose work they sold, a resource center, a place to buy concert tickets, and a venue to meet other bookish women at hosted readings.

It would be wrong to think of feminist booksellers as women who were passively engaged in distributing products others created. As Kristen Hogan chronicles in her 2016 book The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability, staffers took the initiative to compile and distribute book lists and worked hard to build robust sections featuring books by women of color, texts about domestic violence and the effects of sexual abuse, and nonsexist children's stories, among other subjects. Feminist booksellers quickly realized that their combined buying power gave them leverage with publishers. As pioneer bookwoman Carol Seajay wrote in the movement's bible, Feminist Bookstore News, in the late 1970s, 80 stores each selling 50 copies of a new book represented half of the 8,000 books publishers believed they needed to sell to make a profit. Armed with this knowledge, feminist booksellers pushed reluctant corporations to publish or reissue several important works. Bledsoe told me, "I would not be a writer today if it weren't for the feminist book- stores that nurtured the publication of books by and about serious, passionate, smart, and often eccentric women, books that fed my young idealist self."

In the mid-1990s feminist bookstores pushed the American Booksellers Association to sue publishers and wholesale distributors over the illegal practice of offering larger discounts to chain bookstores. By then, though, the end was already in sight. Soon, the chains were themselves disrupted by online stores like Amazon -- which, let's remember, used lesbian-baiting tactics when contesting a trademark-infringement lawsuit brought by Minneapolis's long-established feminist Amazon Bookstore Collective in 1999. Running a successful brick-and-mortar bookstore, which requires heavy investment in inventory, has always been a challenge, but online competition, the recent embrace of e-books, and the rising cost of urban real estate put many feminist, LGBT, and other independent bookstores out of business. Gay bookstores also had to contend with the increased availability of free online porn. In the 1980s, when Lammas was kept afloat by sales of sappy lesbian romance novels, the gay bookstore my room- mate worked at stayed in business thanks to a back room stocked with skin mags.

Most of the stores that remain are kept alive by course- book sales for nearby colleges or sidelines like art, jewelry, and crafts. By the time fictional Madwimmin Books closed in 2002, most of its income came from sex toys and the "library o' lubricants" that had taken over several feet of shelf space.

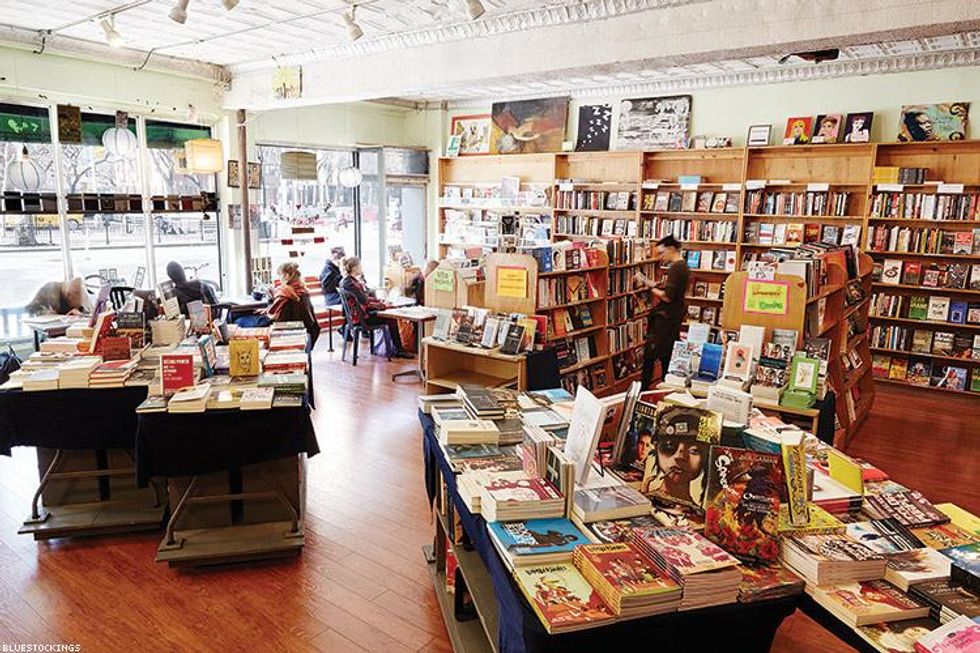

Books still matter, though. In New York, the small but magnificently curated inventory at the Bureau of General Services -- Queer Division, which operates out of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center, is filled with lifesaving and life-changing volumes. And these days, physical spaces are more precious than ever. Recently, while bemoaning the lack of women's spaces even in Manhattan, a young queer woman told me that Bluestockings, the radical bookstore on the Lower East Side, is a rare spot where women can meet in person. Bluestockings is a community center, hosting book clubs, yoga classes, and sober poly mixers. It's the kind of eclectic, activist space where the pioneers of feminist and LGBT bookselling would feel right at home.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes