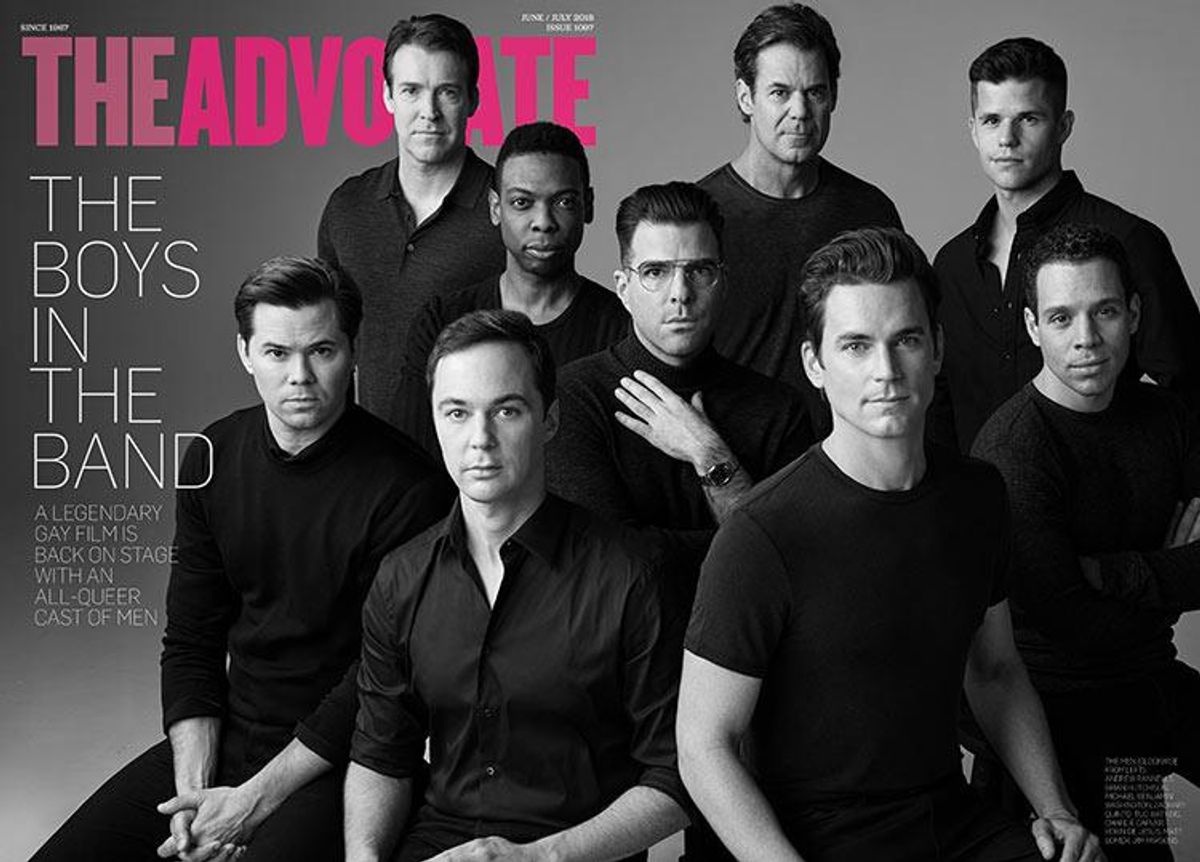

Photography by Robert Trachtenberg, with additional interviews by David Artavia, Neal Broverman, and Daniel Reynolds

The groundbreaking play The Boys in the Band had its debut in 1968, just 10 days after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and mere months before Richard Nixon would be elected president. It showed a group of gay and bi men, on one precarious night in their lives. And while legions of viewers of the play and 1970 film have debated its merits, it should be noted that not a single one of the men dies in the end. In 1968, that was already a happy ending.

Now about a dozen gay men are staging its 50th anniversary revival on Broadway. TV power player Ryan Murphy has gathered a magnificent cast that includes A-listers, stage vets, and heartthrobs -- Matt Bomer, Zachary Quinto, Jim Parsons, Andrew Rannells, Charlie Carver, Michael Benjamin Washington, Tuc Watkins, Robin de Jesus, and Brian Hutchison -- but can they make modern audiences open their hearts to these queer underdogs?

As actor Leonard Frey (as Harold) walks through the door in The Boys in the Band -- first in the groundbreaking 1968 play and later in the controversial 1970 film -- he answers another character's accusations that he's late, and stoned, with quiet reserve.

"What I am, Michael, is a 32-year-old, ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy, and if it takes me a little while to pull myself together, and if I smoke a little grass before I get up the nerve to show my face to the world, it's nobody's goddamned business but my own," Harold says.

The retort perfectly sums up what Harold is all about -- and what most of the men in that room, a birthday party full of gay and bi men, struggled with at a time when LGBT people were pathologized, unable to congregate in public, fired from their jobs, and even arrested for simply dancing together or wearing clothing that expressed a gender identity conflicting with the one they were assigned at birth.

While playwright Mart Crowley's 1968 play was a smash hit, by the time it came out on film -- a year after Stonewall -- gay men in particular were at a different place politically. Many took offense at the self-deprecating wit of Harold as well as the stereotypical mannerisms of other characters, from the wispy femininity of Emory (clearly the queeniest of characters), to Larry and Hank (the couple struggling with monogamy vs. an open relationship), to Cowboy (the young and beautiful but dim hustler), to Michael, the angsty, analysis-driven, self-hating homosexual around whom the friends seem to pivot.

Viewing the play 50 later years, as thousands will do as it opens on Broadway May 31, offers a different perspective -- a bit removed, but still one that may depend on your generation.

"I think in 2010 they asked audiences of this play in their 30s, 40s, and 20s how they responded," recalls actor Charlie Carver, who plays Cowboy in the stage revival. "I think people in their 40s wanted to place some distance between identifying with a lot of these characters, but the young people really went, 'Oh, wow, even though this took place and first premiered 50 years ago, this is me and my friends on some level.' I do believe my friendships are very caring and supportive, but there is this absolute human ability to cut one another down. And so, when I read the play, I see some tragic things, but I also see some sort of humor and the humanity of what happens when a bunch of friends get together and drink too much in an apartment."

Still a bit of a teen idol at 29, Carver--best known for his roles on The Leftovers and Teen Wolf -- is the youngest member of a cast of leading men starring in the 50th anniversary revival of The Boys in the Band. Carver is perfect to play the hunky hustler, known only as Cowboy; as surely as Tuc Watkins, the 51-year-old former soap opera star who has had bit roles on everything from Parks and Recreation to Desperate Housewives, is to play Hank, a soon-to-be-divorced bisexual father.

Watkins, a father of two, and Carver aren't the only queers among the cast either -- all nine actors are gay. That includes The Big Bang Theory's Jim Parsons as Michael; Zachary Quinto as Harold; Matt Bomer as Donald, a guy eschewing his homosexuality; Andrew Rannells as Hank's nonmonogamous partner Larry; Robin de Jesus as interior decorator Emory; Michael Benjamin Washington as Bernard, the only black guy at the party; and Brian Hutchison as Alan, the so-called straight college friend of Michael's.

When Parsons first heard that producer Ryan Murphy (the gay powerhouse behind Glee, American Horror Story, and the upcoming FX musical series Pose) was thinking about putting together this 50th anniversary production of The Boys in the Band, he recalls, "I had heard the title, of course, but I had never read it. I had never seen it, and ... I might have even gotten [the play] confused with And the Band Played On."

When Parsons, whose role is at the center of the show, sat down and read it, he says, the "biggest thought I had was -- and I hope this doesn't sound insulting -- was, What the hell is happening? The way that the men interacted with each other... I was like, what is going on?" That's when he called famed director Joe Mantello, one of the original Broadway cast members of Angels in America, who is now directing Boys.

"I said, 'I have to be honest, I find this both exciting -- but also I'm not sure I fully get it.' And I'll just continue to be honest, do I fully, fully get things? No. We're still discovering things ... but talking with Mantello I immediately felt like it was an adventure and a challenge that I really wanted to take on, as long as he was helming it."

At its heart, the play is an exploration of a group of gay men on one night of their lives, in a world where being gay is socially isolating and being out is unthinkable -- because it means becoming a social pariah. Parsons acknowledges that there are "unpleasant and thorny [elements] about this play and the way these men deal with each other," but says that is "a direct reaction, whether they know it or not, to the society and the oppression that they're feeling."

Brian Hutchison, who plays Alan, agrees. "I think this play in some ways accurately represents what life must've been like for so many people," he says. "I don't have situations I'm in ... that are toxic in this way, where people are cutting each other down in this way, and I think that has so much to do with how far we've come, the ability to be out, to be able to live ... without judgment, without hopefully too much legislation against you, being able to be married -- there's not [as much] concern of losing your job or losing your family or your livelihood or your social standing."

Still, Hutchison admits that many people misread The Boys in the Band. "I think it is really important to understand why they acted like they did. It really wasn't so much a choice to be unhappy or to be an alcoholic or to wallow in self-loathing ... [they wanted] the same things we want: equality and freedom and equal rights and respect and dignity. And society wasn't prepared to give that to those guys, and so there was this rage ... even among their chosen family ... there was still this bitterness and frustration."

As for Alan, the masculine character who ends up punching another man, Hutchison says, "He's so conflicted and so in denial and there's really no answer to the question of is he gay or is he not gay. ... I think many men who may consider themselves. ... masculine don't want to be associated with someone, in Alan's words, that he would call a f****t, a fairy, a pansy, a queer. I think it's probably his deepest fear that in any way he is associated with [femininity]."

Robin de Jesus, who plays Emory, perhaps the show's most empathetic and least self-loathing character, says he couldn't really engage with the 1970 film, "But when I reread the script ... I instantly thought about ... the concentration camps in Chechnya. Because what I saw in the play was the struggle of dealing with PTSD and all I could think about were all those folks ... and what happens if and when they come out. Who knows what sort of torture they've been put through ... or how they'll be accepted by society if they're integrated back."

A double Tony nominee ( In the Heights, La Cage aux Folles), De Jesus sees the men in the play struggling with this trauma. "To be a gay man in that time period means you're probably bound to stay in the closet," he says. "Or if you were courageous enough to come out, you were probably kicked out of your family. Those that you've loved the most now just disown you. And living in complete secrecy, which leads to shame. So how can you healthily interact with other human beings? For my character, Emory, he is hands-down the most flamboyant, effeminate one of the group ... he couldn't hide that. Everyone instantly knew that he would be a 'nelly.' I just imagine Emory as a kid being constantly told, 'Stop being a little pansy. Act like a man.' So that's sort of the PTSD I'm talking about."

He continues, "When you are part of an entire group of people who have all been told, 'You're not worthy, you're not significant, you are no good'... it's going to trigger some shit. And so, how do you deal with that? That's what this play is about. There are a lot of people who have very harsh criticism of this play ... because it makes them feel like this is a negative portrayal of us. But I think what they don't understand is that it is a negative portrayal proving a point: that this is the effect of all the baggage that's been put on us."

Parsons, who has been with his husband, Todd Spiewak, 16 years now, says that LGBTs have made great strides in the past five decades, but we can't rest on our laurels. "You hear the word complacency," Parsons explains. "Be it about gay rights or the AIDS epidemic. A play like this is worth revisiting on many levels, but one of them being, it's not impossible for this type of situation to happen again. [We] always run the risk of an oppressive 'other' rolling back the clock."

Above: Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, and Matt Bomer

MOVIE HISTORY

Part of the reason The Boys in the Band was so groundbreaking is that it was one of the first films to have gay characters at all. The Hollywood Production Code, which lasted from 1930 to 1968, put a stranglehold on any portrayal of "sex perversion." Sure, some subtextually gay characters (think Rebel Without a Cause) made it to the screen, but in Boys, the characters are up front about being gay. And whether they hate themselves for it, there's no mistaking that this is a room full of men who self-identify as queens, fairies, and fags. Nobody watching the the play could mistake them for anything but queers.

Straight director William Friedkin (who later gained fame for directing The Exorcist) was called brave for making the 1970 film, which many Hollywood insiders thought would be a career killer. But critics agreed that only two years from stage to screen meant that Friedkin wasn't hired to improve on the play, just to preserve it for a wider audience.

Looking back, actor Zachary Quinto reminds us the play is set "at a time when the only place where gay men could be open and authentic with themselves was in private. There wasn't the freedom that we enjoy today, and I think probably the most significant evolution in the past 50 years is the ways in which we as an LGBTQ community have become more integrated and more authentically ourselves."

Still, "the evolution of the vernacular and the colloquial mode of communication, which I think in some ways evolved from a need to release a certain kind of pressure ... that still exists [today]."

"It's true how much has changed, and how much hasn't changed," Parsons says. "At the risk of ... generalizing, it seems to me that there is not a moment, a reaction, a statement, a feeling, a take on anything that any of these men have in this play from 50 years ago that can't be and isn't daily replicated in the lives of gay people now -- just perhaps not to the same degree. Some things still do elicit the same kind of reaction. It's not by a black-and-white flip of the way things were to the way things are."

Quinto, perhaps best known as Spock in the new Star Trek films, also had conversations about Boys with Murphy, Mantello, and producer David Stone.

"I feel like I have a much deeper, fuller understanding of the play now, and towards its resonance and its power," he says. "It was sort of stigmatized when the movie came out. It's been really nice to get to know it with fresh eyes."

The actor, one of Hollywood's most sought-after stars, came out less than a decade ago, moved by the 2011 suicide of young queer activist Jamey Rodemeyer, which reminded him that LGBT kids were still killing themselves even as courts legalized same-sex marriage. Quinto wrote on his blog that after Rodemeyer's death "it became clear to me in an instant that living a gay life without publicly acknowledging it is simply not enough to make any significant contribution to the immense work that lies ahead on the road to complete equality."

It's telling how youths have impacted many of these actors: Watkins is raising 5-year-old twins; Bomer and his husband (publicist Simon Halls) have three kids; Quinto's earliest activism was for the Trevor Project and It Gets Better, both aimed at preventing LGBT youth suicides.

"You know, The Boys in the Band and I are the same age, actually," says Watkins who was born in 1968. "At 50 years old, I'm the oldest guy in the play, and Charlie is the youngest guy in the play. I would guess that even though he's half my age I probably have twice as many fears about what it means to be gay than he does, which is really a great thing, because it means that we're standing on the shoulders of giants -- gay men and women who came before us, who paved the path."

He feels differently now than he once did about "stereotypes" on the lavender screen. "I feel like I'm sort of a time capsule of the gay experience from when this play was written," Watkins says. "When I was born, to where we are now ... I've taken exception with my own community and the representation of gay people in the TV and film industry ... I had a problem with what I thought to be stereotypes, particularly over at Modern Family. That was a number of years ago, but the problem I had with seeing gay stereotypes in entertainment was just that. It was my problem."

The actor admits that the culture he grew up in during the 1970s and '80s, and the industry in the '90s, "reinforced in my head that being gay was not OK. I still have feelings about what it means for me to be gay, but ... [I] want to do better. I plan to make things better by making people feel safe being themselves around me because I, in turn, want to feel safe being myself out there in the world."

Unsurprisingly, Carver has experienced masculinity in very different ways, and he hopes the femmephobia in the play is a relic of the past. "That is something that I hope we are beginning to contend with more deliberately and compassionately now. I experienced a lot of internalized femmephobia growing up." Carver says coming of age as historical changes like marriage equality happened, "my feelings about myself and my masculinity have [also] changed. I think what's really exciting about being a young person--about young, gay, queer, LGBTQI+ culture now -- is this sort of queerification of gender."

For actors like Parsons and Carver, coming out was smooth. Their careers as out actors are successful. Things were much different for the original cast of Boys, a number of whom were also gay. Laurence Luckinbill, who originated Hank is married to Lucie Arnaz and is the uncle of transgender film directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski. He played Spock's half-brother in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Peter White, who played Alan, became a soap star on All My Children and Dallas. Luckinbill and White, both straight, are the only two stars still thought alive. Reuben Greene, who played Bernard, faded from public view in the '90s. Cliff Gorman, who played the flamboyant Emory, went on to macho TV roles on Law and Order and Police Story before his 2002 death from leukemia.

Kenneth Nelson (Michael), Leonard Frey (Harold), Frederick Combs (Donald), Keith Prentice (Larry), Robert La Tourneaux (Cowboy), Robert Moore (the play's original director), and producer Richard Barr, all died of AIDS complications.

"A lot of them had great careers," Bomer says. "Unfortunately, we had this horrific epidemic that swept through our people. I look back and say, 'Wow! These guys were 10 times more courageous than someone has to be now.'"

La Tourneaux, who played the naive working-class sex worker among a sea of middle-class men, fared the worst. He told reporters that Boys had been the kiss of death as an out gay actor. Unable to score other roles, La Tourneaux modeled nude for gay men's magazines, had a naked cabaret act at New York City's Ramrod, and once told reporters he had an affair with actor Christopher Walken. Eventually La Tourneaux turned to sex work, advertising his services in The Advocate (back when adult ads were still a part of the magazine). After a fight with a nonpaying client, he was sent to Rikers Island, where he attempted suicide. Three years later, he was lost to the AIDS epidemic. Gorman and his wife cared for La Tourneaux in his final days. What's clear even now is that Charlie Carver, who plays Cowboy in the revivial, the role that pigeonholed La Tourneaux as a gay hustler, won't suffer the same fate.

Above: Brian Hutchison, Tuc Watkins, and Andrew Rannells

STEREOTYPES OR REALITY?

The first time Watkins saw the play The Boys in the Band, it didn't impact him much. Rehearsals changed that, he says.

"I think when you put people like Jim [Parsons] in a role where he's really funny but he also turns really dark -- he's a great ambassador to see how the play is wickedly funny, but it's also really emotionally raw. The people that they've populated this play with really make the message pop."

What caused Parsons initially to ask, "What is going on?" left Quinto asking, "'Wow, how are these people friends?' But you have to take into consideration -- and what I think the play is really exploring -- is this projection of self-loathing. That these characters exist in a society which belittles them, berates them, attacks them, arrests them, persecutes them to a degree that reinforces such depths of self-loathing that I think we have evolved beyond. There's still a lot of backwards thinking and a lot of bigotry against LGBTQ people in this country -- without question -- especially under the auspices of the current administration. But I do feel like we've moved beyond the place where the LGBTQ community is at the mercy of how they are perceived by mainstream, heteronormative society."

In many ways, Quinto adds, the lesson of Boys is that we must learn to not hate ourselves so much. "In his despair and drunken stupor at the end of the night, what Michael is left with is this desire to not hate ourselves so much and then maybe we wouldn't be so brutal with one another. Though there are certainly undercurrents of catty shadiness, there is a kind of wit and repartee in which certain kinds of gay men still relish. That's part of what makes the community so colorful and dynamic in certain ways ... but it goes too far [in Boys] and it gets fueled by booze and drugs and all the extenuating circumstances."

"I don't think there's much different about the way we treat each other," says Rannells. "There's a lot of value placed on wit and intelligence and sometimes that comes in the form of taking people down -- and in the most clever way and the most creative way. My group of friends, we sort of go at each other pretty hard sometimes and it's sort of half performance, half truth ... but as long as you package it as a joke, it becomes a little more palatable."

In the play, "when Donald says something mean to Michael, or Michael says something to Harold, everybody else is laughing. And sometimes the people who are the focus of the lines are also laughing. This is the way that we communicate with each other," Rannells says. "And when taken too far it doesn't feel great, and it's not helpful. That's when it becomes I think a detriment to our community, when it's just mean."

Washington argues, "We're in a Real Housewives world and people are so used to seeing 'friends' treat each other in very, very radical ways and then make up very quickly. So it's not just the gay microcosm that that's in. It's an American pastime now of being very witty to the point of maliciousness. Sometimes I forget that [Boys] was written 50 years ago because the pronoun switching and the boys calling each other 'she' all the time is part of the culture now ... when you start adding in the liquor, that's when people's tongues start getting sharper."

Above: Michael Benjamin Washington, Robin De Jesus, and Charlie Carver

TRUMP'S AMERICA

While queer audiences after Stonewall, especially during the 1980 and '90s era of respectability politics, have fretted over the stereotypes in The Boys in the Band, one enigmatic character reminds us this play came out the same year that Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, protests against the Vietnam War became fiery, two athletes gave the fist-up Black Power salute at the Olympics, President Richard Nixon was elected, and people across the country were protesting for the rights of women, people of color, and LGBTs. In short, it was a political year a bit like the one we're in.

Bernard, the bookstore worker and sole black man at the party, is brought to life by Michael Benjamin Washington, who is probably best known for playing Donald, the same-aged "son" of Tracy Morgan on 30 Rock. Washington, who penned and starred in Blueprints to Freedom: An Ode to Bayard Rustin, about Rustin's role in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, had already been working on another show about April 1968 when he heard about The Boys in the Band.

"Maya Angelou was planning her 40th birthday party," Washington says, "to tell her sophisticated New York friends why she was shifting from Black Power and the Malcolm X way of thought, from 1965 when he was killed, to rejoin Dr. King and the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], which was a big shift from Black Power back to black Christianity. And as she was preparing for this party, she told Dr. King, 'Let me have this party first and then I will join you.' He went to Memphis. While he waited for her to join him, he was assassinated, which triggered her second bout of mutism. My play explores how Jimmy Baldwin, one of her best friends, got her to drag her pen across her scars to tell what happened to her the first time she was a mute, and how I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was created."

As the script for The Boys in the Band arrived, Washington recalls he "Googled it, and realized that it opened in April of 1968. I got this goosebump up my spine."

Both Bernard the character and the original actor who played him remain a bit enigmatic. Reuben Greene has been off the grid since the 1990s. In his last interview, with Lawrence Ferber for Windy City Times, Greene reflected on his Boys character: "I think the main thing was he was isolated as a black person and a homosexual." Greene also said that because he wasn't gay, a gay actor might portray Bernard differently. "There's another experience that someone else can bring. Someone who has had that experience."

Fifty years later, Washington sees Bernard as being at a crossroads. "I find that all of the men in this play are struggling to figure out who they are in the context of a political scene that's very, very hostile," says Washington. "I was really drawn to the idea that Bernard, this black man in this white world, whose friends are -- at least at this birthday party -- all white. I think this play opened April 14, 1968, and Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on the 4th, Bobby Kennedy in June. This great integration experiment is imploding right in front of his face. So, how did he survive inside of this tribe where it too is imploding? That seems to be the biggest parallel [to today]. What is the price he pays to be a member of this tribe -- and [what does] it costs him to remain there? The Black Power movement was just giving birth in 1968. So, this man is going to have to make a lot of big decisions soon about the tribe that he wants to ally himself with. And I think because of the timing of when Mart [Crowley] wrote it, right before Stonewall, right before everybody had to make decisions about their own liberation -- gay, black, straight, women, and otherwise -- Bernard really represents to me that person who was once on one side of the fence, now is on the fence during the play, and we kind of wonder when he exits at the very end, which side will he be on tomorrow?"

In The Boys in the Band, the oppression and stigma that keeps these men in the closet is ultimately what is responsible for making them depressed, anxious, suicidal, or prone to addiction. It's not an inherent psychological pathology that LGBT folks share. That's a particularly resonant message even in 2018. As some states ban conversion therapy while others find religious loopholes, watching a character unravel like Michael, a devout Catholic, can remind us of how many people in certain religious communities still suffer.

There are other issues just as relevant. Rannells discovered the movie at a Nebraska Blockbuster as teen and at first found it both confusing (Why are the friends "being so mean?") and a bit inspiring ("Look, I can have a life where I'm just with my friends ... living [my] authentic life, in New York City"). Rannells's character, Larry, and Tuc Watkins's Hank, are the only two characters that are in an active relationship. Their argument, Rannells says, is one a lot of couples and particularly a lot of gay couples still have: "Is monogamy something we should be striving for? That sort of heteronormative mold -- is that something that men, and gay men specifically, should be trying to attain?" For Larry, like thousands of men, even in the age of marriage equality, that doesn't feel like a realistic or honest goal.

"First of all, to have a couple that is committed to each other in many ways, in 1968, but yet still struggling with this idea of should we open up the relationship, should we not ... that's a conversation that certainly people are still having today," Rannells says. "I think the danger is saying that 'this works for everyone' and that's not the case. It's not only about who you're with, but where you are in your own life, and your own process. I love that Hank and Larry are sort of in the midst of hashing all of this out in this party. I feel it's a very contemporary conversation to be having."

There's an old Lakota proverb that says people without history are like wind on the buffalo grass. Americans love to say that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. That's not a concern for Watkins.

"I think young people are actually very in tune with their history," Watkins says, although he acknowledges that some may ask "'Why should I see it today? There's self-loathing. ... Why do we want to go back and watch that?' Well, I understand that. But we do have to look over our shoulders and understand why we are allowed to do what we're doing because of the people that came out [before] us."

Carver agrees: "It's important to know one's history because not only does it lead to a sense of appreciation for what you have, but I think it galvanizes one toward protecting that and trying to usher in whatever the next phase of liberation may be."

Each man here recognizes the privilege of being at this point in history. These characters show the lengths LGBT people have gone through for their friends, especially in decades where most were cast out of their family of origin for being gay.

"The thing is, ultimately, these guys are all in it together," says Quinto. "They're all up against the litany of social adversity that was just a hallmark of the early to mid-1960s America, and still exists in some vestige today. That's where the camaraderie comes from; they can eviscerate each other ... and say horrible things but at the end of the day they're there for each other, they understand what each other is going through and they've got each other's backs. That's the beauty of the play ... showing up for your brothers and being there for them in their moments of grace and moments of indignity, and understanding in a different world, maybe 50 years from now, we won't have to endure these same kinds of attacks and diminishments that fuel this kind of bitterness. And luckily, by and large, we can say that's true."