The only thing as stunning as the reversal of fortune for marriage equality from 2004-2014 is the way in which workplace fairness for LGBT Americans has languished at the federal level. True, the Senate made an impressive push to pass employment protections last year, but the House of Representatives remains a sizeable hurdle to their final passage.

The juxtaposition is particularly interesting if you compare the progression of the gay rights movement to that of the civil rights movement of the 20th century--a model LGBT leaders and historians have often looked to for benchmarks and inspiration. The civil rights movement moved from integration of the armed forces (1948) to the desegregation of schools (1954) to prohibitions on discrimination in public accommodations, the workplace, and voting (1964-1965), and finally to the eradication of the anti-miscegenation laws that banned interracial marriage (1967).

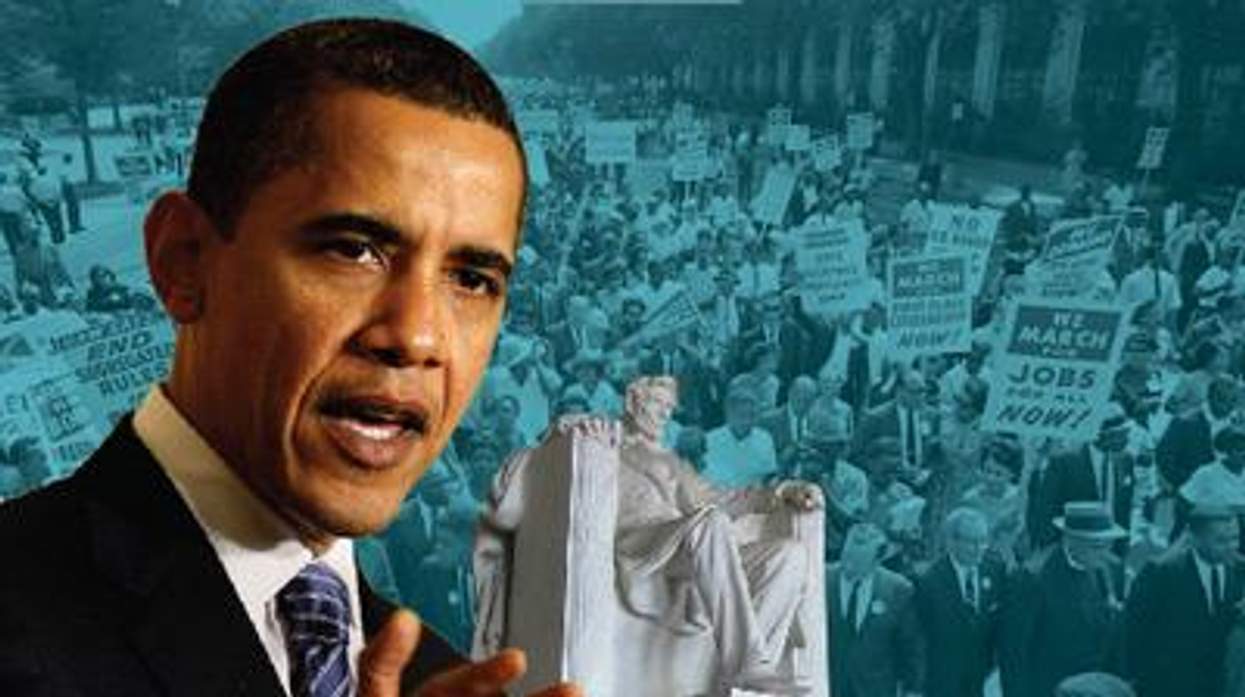

President Barack Obama, a keen student of civil rights history, reminded me of this order when I interviewed him on the campaign trail in 2008.

At the time, I was pushing him on his stance on civil unions. "Is it fair for the LGBT community to ask for leadership [on marriage equality]?" I asked him at his Chicago-based campaign headquarters in April 2008. "In 1963, President Kennedy made civil rights a moral issue for the country," I continued, referring to JFK's historic address to the nation.

Then-Senator Obama pushed back with a strategy argument. "But he didn't over- turn anti-miscegenation. Right?" he asked.

"I'm the product of a mixed marriage that would have been illegal in 12 states when I was born," he explained. "That doesn't mean that had I been an adviser to Dr. King back then, I would have told him to lead with repealing an anti-miscegenation law, because it just might not have been the best strategy in terms of moving broader equality forward."

But six years later, the march toward marriage equality has hit the fast track, while federal employment protections-- a critical advancement for the civil rights movement--have practically stalled. Indeed, at the time of this writing, the number of marriage equality states has now caught up to the number of states that prohibit discrimination against LGBT employees: 17. (This does not include pend- ing marriage cases in Utah and Oklahoma.)

Image credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images (Obama); Courtesy of Getequal (Banner); AFP/Getty Images (March)

In part, this progression reflects a distinctive difference between the adversities faced by LGBT Americans and black Americans. Gays did not need to be emancipated, granted citizenship, or given the right to vote. Generally speaking, LGBT citizens have not needed to be "let in" because they already existed in every corner of American life, though often without detection. What they have really needed is to be seen and counted by the federal government (a major failing during the onset of the AIDS crisis) and then given the necessary protections from being expelled once they were known. The clearest form of government-sponsored discrimination against lesbians and gays was "don't ask, don't tell," and it was the first to go. But employment protections were perhaps prioritized early on by civil rights leaders because people of color often faced being shut out of gainful employment altogether, while LGBT workers have typically been at greater risk of being harassed or fired once they were discovered.

In fact, in the run up to United States's involvement in World War II, A. Philip Randolph and other black leaders demanded a presidential executive order that would prohibit race-based discrimination by federal defense contractors, which were quickly becoming the nation's economic engine. After the leaders threatened to march on Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the order in 1941, a major milestone for the civil rights movement. That order was subsequently enhanced by Republican and Democratic presidents alike until Lyndon Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 in 1965 requiring all federal contractors to ensure fair employment practices regardless of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Congress also followed the early lead of the executive branch by enacting federal workplace protections through Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

LGBT advocates have long sought a similar executive order that would prohibit federal contractors from discriminating against gay, bisexual, and

transgender employees. Such an order would provide binding legal protections for some 28 mil- lion workers, of which more than 6% are likely to be gay or transgender, based on workforce estimates from the Williams Institute. As the Human Rights Campaign noted in a 2008 transition document pre- pared for the incoming Obama administration, "When the federal government hires private companies to perform government functions with public funds, it can and should expect the contractors to adhere to the same civil rights standards as the government would if it were doing the work."

Meanwhile, the Defense of Marriage Act has effectively been gutted and we are fast approaching the day when the Supreme Court will hear a second case arguing that same-sex marriage is a fundamental constitutional right.

It's a curious turn of events. In politics, as in journalism, you go where the energy is, and there are many reasons why work- place fairness still hasn't caught the fire that the "don't ask, don't tell" repeal and marriage equality have. But at least one of them is executive influence. President Obama famously inserted 32 words into his 2010 State of the Union address that started the clock ticking on the gay ban. He also took to the airwaves in 2012 to announce his change of heart on same-sex marriage. While neither of these actions definitively altered the trajectory of either issue, they most certainly catapulted them forward at an accelerated pace.

But had I asked him in 2008 whether he anticipated that marriage equality would start to sweep the nation before basic employment protections were extended to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans, I suspect he would have said, "No."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes