Exclusives

How to Fight Fascism and Erasure in 45 Thoughts

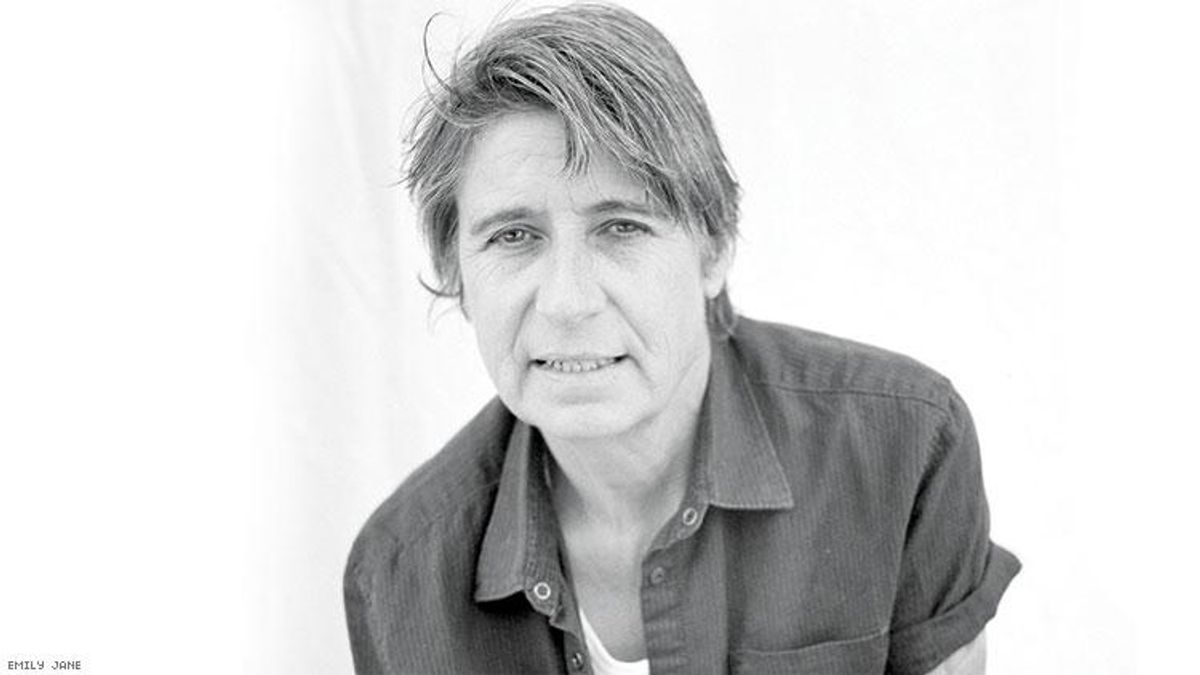

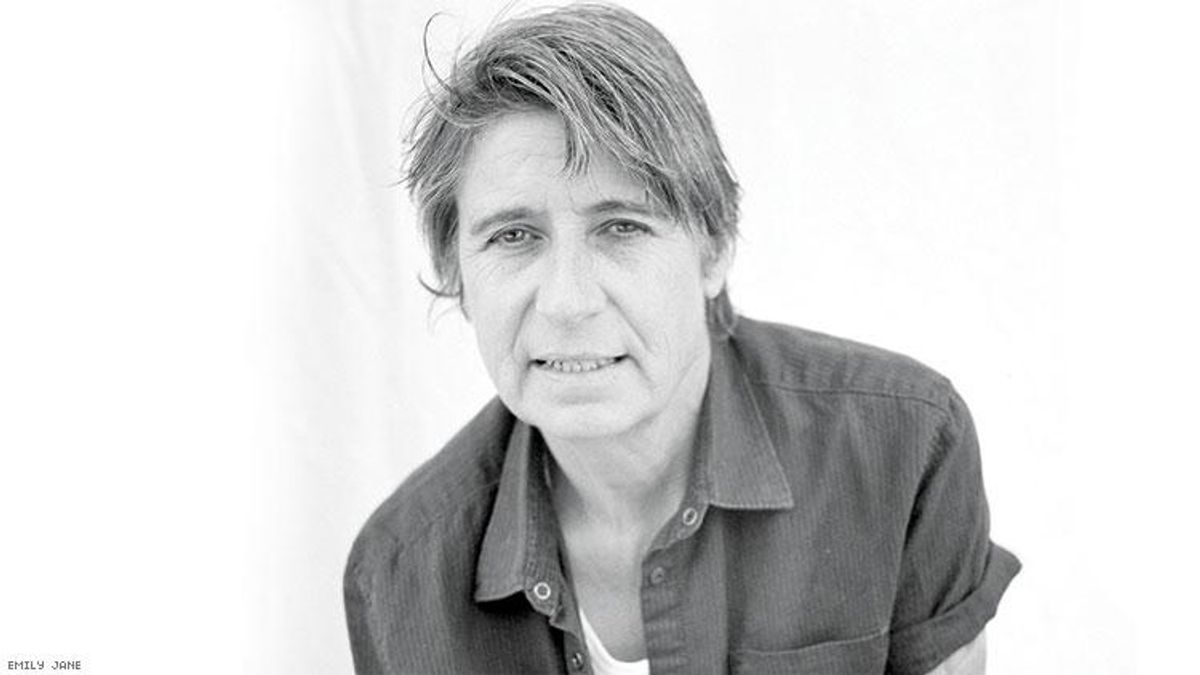

Author, musician and activist Lynn Breedlove talks his new book, genocide, resistance, and using art to survive hard times.

August 27 2019 12:00 AM EST

October 31 2024 5:54 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Author, musician and activist Lynn Breedlove talks his new book, genocide, resistance, and using art to survive hard times.

Since Tribe 8 burst onto the San Francisco music scene in 1990 and helped introduce queercore and dyke punk to the world, dildo-wielding lead singer Lynn Breedlove has been a badass. Today, he is also an award-winning author, performer, entrepreneur, and activist. Breedlove's 2002's novel Godspeed introduced a meth-using bike messenger protagonist (based in part on himself). It garnered a cult following and when the writer-performer's solo comedy show, Lynnee Breedlove's One Freak Show, was turned into a book, it won a 2010 Lambda Literary Award.

Breedlove is also the founder of the not-for-profit startup Homobiles, a ride service for the LGBTIQQ community and allies, for which they received the 2012 Harvey Milk LGBT Club Award for Activism.

Breedlove's latest book, 45 Thought Crimes, addresses the effects of genocide, being from a blended family, and wrestling with identity -- but it also celebrates co-conspirators, anarchy, indigeny, survival, and resistance.

Why are part one and two both called "A Call to Arms?" I fell in love, and two minutes later we had a dictator in charge. What began as a series of daily love poems became spattered with rage. As the trans offspring of someone raised in Nazi Germany, my mother, I considered leaving the country. But my dad, who taught history, said, "In this family, we stay and fight." My girl, Steph Joy, said, "Wait, we just fell in love." She collected these pieces and arranged them along a storyline. My publisher decided on the two parts. I think of it as it a call to arms. To link, to hold each other, as well as weapons, our voices. War. Love. All of it.

The topic of blended Native ancestry is a sensitive issue. Why share the story of your family's attempt to suppress theirs? I wasn't going to share. My dad has stories and photos, family trees. I research and report back to him. We theorize to fill in blanks. I hesitated to tell anyone. But I write inmy room, then someone says, keep going -- and the next thing, it's a book, a band, or a show. It felt vulnerable, but I hoped it would inspire readers to search their history, consider responsibility to the dead and the living, reparations, to live with integrity and personally dismantle racism to examine patterns and create change.

I have been invited to ceremony by friends, and it's a heart opener. I try to imagine what ancestors might ask me to do, what fight they would want me to carry on. My great-grandfather was trying to tell his children and grandchildren something about being half- Indian and born on a rez, which at that time was scary to do, and he could have hidden it, but he wanted us to know. Every generation, we move a little. So the meditation is to honor those who fought to get us this far by making this place better now.

Can you share your mother's story around World War 2? She's from Germany, but not Jewish. She watched the fallout of Kristallnacht, the firing of teachers who refused membership in the Nazi Party, the disappearance of Jewish classmates. So she was forever deeply mistrustful of any government. She told me, "Go ahead and sit down during the Pledge of Allegiance -- I had to salute the swastika as a child every day and look where that got us." She taught me everything I knew about anarchy. She also maintained that while you may not know all the horrors going on in your name, it is your responsibility to find out about them and try to stop them. She took me to the Anne Frank house, the camps, and Jewish museums. She taught me about swing kids, the White Rose, and Von Stauffenberg. So in her honor, I research hard and make art that's uncomfortable.

In "Il Lourdes," you write, "My grandfather who tried to look away from his Indian-ness married my grandmother who didn't know she was Indian. Or she looked away." Why do you think they were looking away? In the days of my grandparents, it was not OK to be brown. My grandmother worked in the backroom with all the other brown ladies in the '50s, in downtown Oakland, running the switchboard. The white ladies worked the floor. But she dyed her hair blond when she went gray, insisting she was Spanish and French. That was more acceptable and might explain her olive skin. Her real ethnicity is unknown. She was adopted. The pieces called "Stolen Histories" discuss cultures obscured by Indian schools, adoptions, intermarriage, the taking of names.

In "Sam Clam's Disco, Back in the Day," you write, and mourn, the loss of the old San Francisco, where tacos were 99 cents and the Mission district was a very different place. Do you think that recalling and celebrating that history has an effect? I was born in the Bay Area and I've been here through three booms. Each time, we re-created the scene wherever we landed. The challenge is to find each other... We think social media connects, but the definition of a screen is something that separates. I also wrote in the book about Fado -- a musical tradition native to Portugal -- because it was a way that people found each other during their 44 years of fascism. An example of how we use art to sublimate, as a salve and armor, and even a weapon, to survive hard times.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella