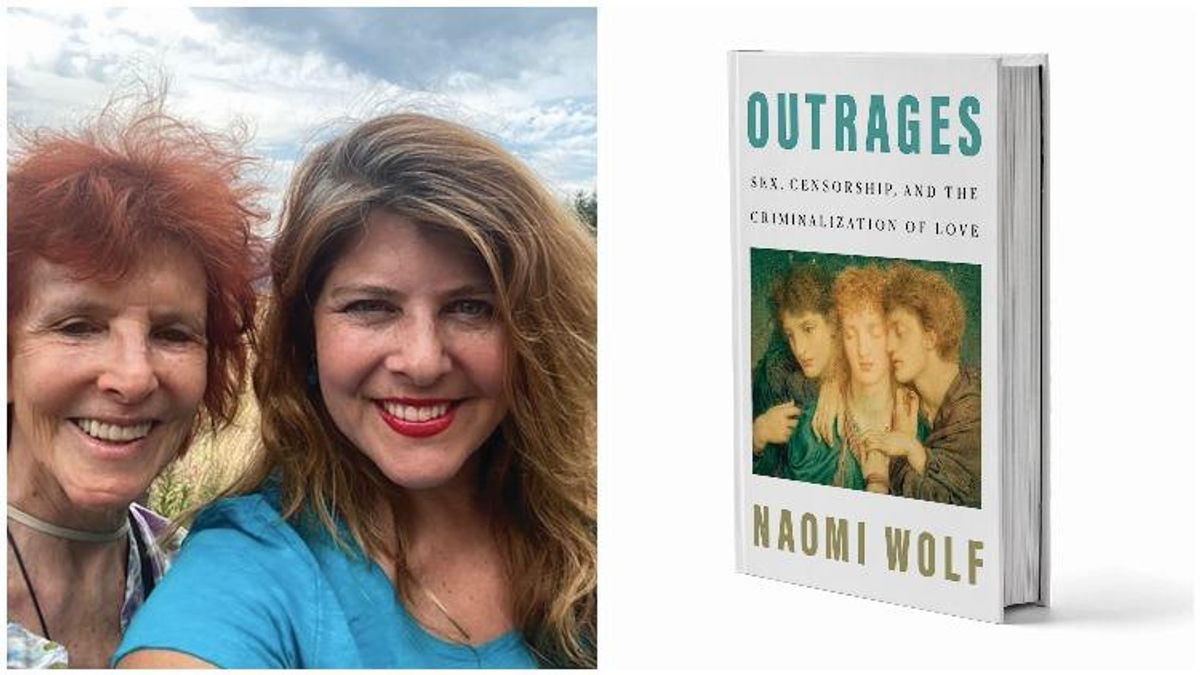

Naomi Wolf's latest book, Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love, was initially scheduled for publication last year. But after its release in the U.K, the publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, abruptly canceled its U.S. distribution and even directed "librarians to destroy the book," says Wolf, a feminist author known for The Beauty Myth. It's an odd parallel to the content of Outrages, which details the censorship and destruction of LGBTQ+ literature in 19th-century England.

Now expanded and released by a new publisher, Outrages traces the rise of state-sponsored censorship and homophobia to an explosion of infectious diseases in the 1800s, after which "filth" was seen not just as a personal issue but a public one. The British government later expanded its reach to words and ideas it considered dangerous to public well-being.

At the center of the 2019 controversy was a disagreement about some historical data that Wolf cites in the book regarding men executed in Britain for the act of sodomy. Wolf's critics argued that the data reflected the execution of rapists and pedophiles, not gay men.

Wolf says the law in question "was written so that it didn't distinguish between essentially adult sex and acts of violence." She adds, "Fifty-six men were executed for 'sodomy' in the 19th century [in England]. You cannot say that they were all rapists and child molesters. That's just not true. And I think it's a very homophobic thing to say. What concerns me...[are the] news outlets that asserted that that didn't happen. It erases the fact that the British state did engage in this atrocity. That it did execute at least some men who were consenting adults having sex with each other."

Wolf argues that homophobia was clearly at play in the Victorian-era cases, even when the men were accused of violence or acts with children, because the victims in these cases were more likely to be male. To be clear, she's not excusing predatory behavior. "I'm a survivor of child rape," she explains. "It's very close to home. [But] when it comes to predators, if you are a cisgender white heterosexual man, you have much higher chances of being a predator with impunity." That these men received death sentences is "another example of queer people being targeted as the problem, whereas when heterosexual men rape children, the state does not prosecute it correspondingly...or proportionately."

Wolf connects this reflection to modern-day trans-exclusionary radical feminists who claim they are just trying to protect women and children with their transphobia. "I want to speak to what is horrifying about engaging with these battles, with these TERFs," she says. "They're always, always, always creating a narrative of trans people in women's bathrooms, and the trans person is always a potential child molester or a rapist. And this is [not only a] completely, statistically fake story, but it's a fake story that's being used to scare and intimidate and mislead a whole nation. And what it does that infuriates me as the survivor of a heterosexual male predator is that it erases the fact that statistically you are overwhelmingly likely, if you're going to be molested as a girl, to be molested by a heterosexual adult man."

"Bathroom laws are absolutely not trivial or marginal or only affecting people who are gender-nonbinary," Wolf notes. "They absolutely affect all of us...because when the state gets to say what your body can do, what you can do based on your body, that is a gigantic breach of personal autonomy and individual freedom. When the state decides that your body is wrong and starts to legislate about it...it creates a context for stripping away protectors to due process, to equal rights, to just being an equal member of the community."

Furthermore, when a type of body is held up by the state as "an object of hatred and contempt," it gives permission for violence to follow, she says: "Hatred has death rates even in an advanced society where you're not supposed to kill."

Outrages traces the creation of these laws that granted the state new rights in regulating different types of bodies and bodily functions. But the book is also an ode to 19th-century author John Addington Symonds (before), who Wolf argues played a significant role in the formation of modern ideas about sexuality and identity.

Addington Symonds

Addington Symonds

"He was a great romantic," Wolf muses. "And his whole life, Symonds, all he wanted to do as the center of being a writer and a critic and a poet and a lover, I would say, was to tell the truth as he saw it about the beauty and nobility of love between men and sex between men. And at the end of his life, to advocate against the laws that discriminated against them so severely."

Wolf sees Symonds as an early LGBTQ+ activist who responded to "powerful homophobic forces around him," including the state censorship of his queer manifesto, A Problem in Modern Ethics. "You literally never know what your advocacy will do," she adds of Symonds's efforts. "You never know what your courage will do, especially in a time of bad laws and bad leadership."

Wolf's observations could just as easily be made in looking at the impact of her own maternal line. In graduate school, her grandmother documented Chicago's gay male subculture of banquets and parties and later worked with Margaret Sanger (considered the founder of Planned Parenthood), providing birth control to other women back when doing so was illegal.

In the late 1960s, Wolf's mother, Dr. Deborah Wolf, was friends with lesbian trailblazer Phyllis Lyon, a founder of the Daughters of Bilitis. Then, working on her Ph.D., the elder Wolf recalls that Lyon convinced her that as a straight researcher, if she conducted an ethnographic study on the lesbian community and how they raised their kids, she could later support lesbian moms as an expert witness in custody cases. So that's what she did, publishing her findings as the book The Lesbian Community and testifying on behalf of lesbian mothers as an expert on the psychological health of lesbian-headed families.

The younger Wolf remembers her mother's work having a big impact on her as well. "And I remember being really scared by it," she admits. "From a child's perspective, you don't care who your mom is sleeping with, you just want your mom. You don't want to be taken away from your mother. I think that really affected me, that homophobia could break up families and keep people from the people they needed."

Later, Wolf had kids of her own but was struggling as a newly divorced mom. "I didn't know how to give my kids that stable, secure family structure that I had had growing up in an intact nuclear family," she recalls. "I felt like a tiny boat in a big sea." But then two gay male couples who were family friends stepped in. "And as my kids grew up, these men and their love...did give us that stability. And it did give my kids role models for lifetime commitment."

"Love is a precious resource in society and anything that harms that or dams it up or punishes people for loving hurts everybody," Wolf concludes now. "I experienced that both as a 10-year-old child, listening to my mom talking about these kids who are going to lose their moms because their moms loved each other. And then myself as a single mother, benefiting from there being extra love left over to give to me and my kids."

As far as her own sexual identity, Wolf says, "I don't think I can identify myself as a queer person. If I were privately queer, I would be publicly queer. What I do resonate with is...I personally feel that the label straight is too rigid. ... I don't see gender as a barrier or a reason in my personal case to be attracted to someone or love someone. If I fell in love with someone, I would want to be close to them, whatever gender they happen to be." She sees an affinity in that sentiment with Symonds, whose literary work imagined our more LGBTQ-friendly times and in doing so, helped bring them to life.

"Censorship is one true meaning of death," Wolf writes in closing Outrages.

"Their vision didn't die because they evaded the censors," Wolf explains now about Symonds and other queer writers like Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde. "That is death if the censors are allowed to do away with books...because some books will go on to give life to people and to create a better and more just world."

"He never shut up," Wolf adds of Symonds's resilience in the face of state-sanctioned repression. "[And] his words did prevail and changed our world and made the world we live in."

Addington Symonds

Addington Symonds