Queer sex was a prominent theme of independent film in 2006, with movies as different as Quinceanera, Puccini for Beginners, The Bubble, Boy Culture, and Another Gay Movie featuring various states of same-sex coitus -- sometimes presented as romantic, but sometimes as exploitative or laughable. Then there was John Cameron Mitchell's Shortbus, which didn't just depict gay sex as hot and satisfactory; it showed it up close, blowing many minds with its blend of cogent storytelling and on-camera masturbation, threesomes, penetration, and ejaculations.

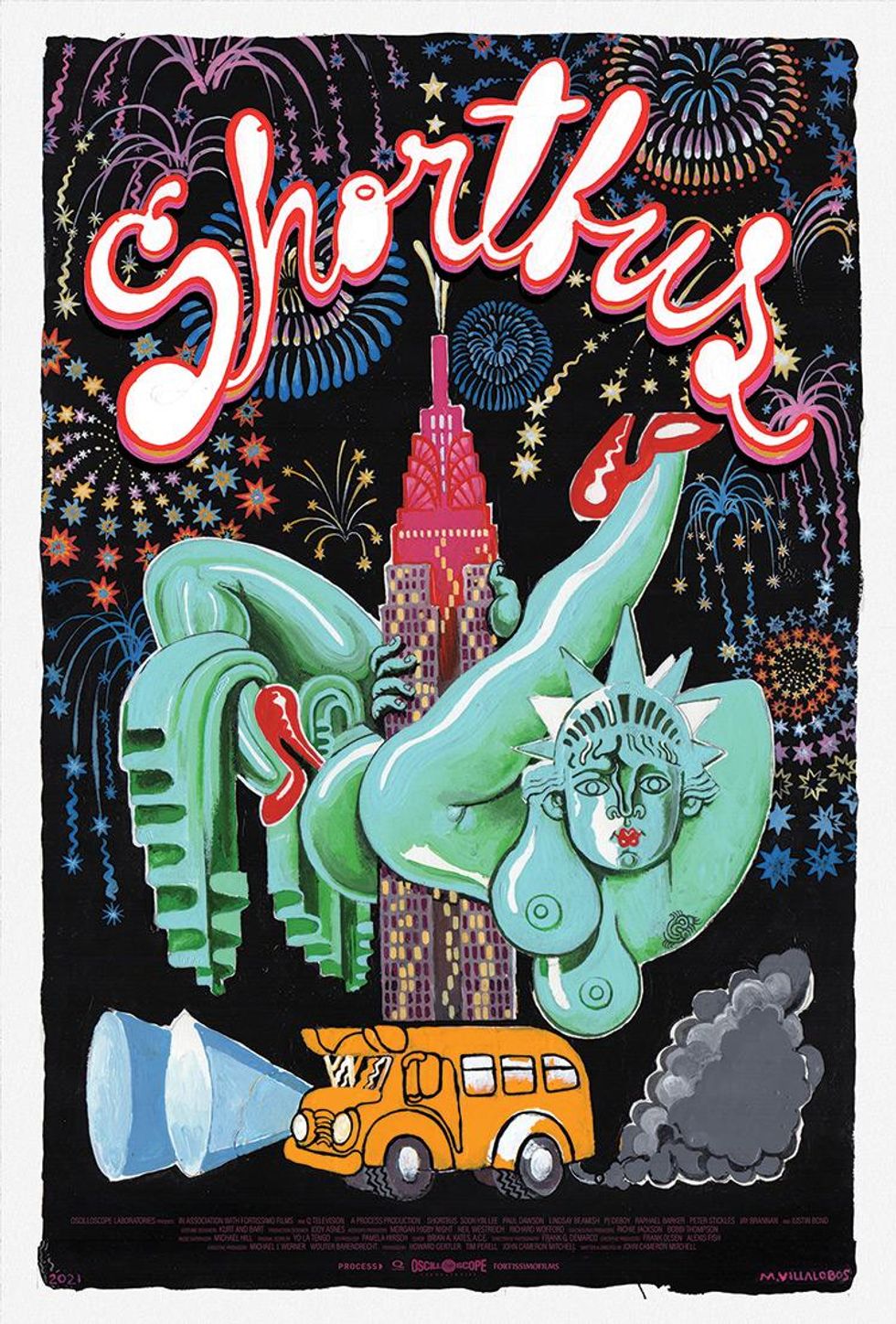

But Mitchell -- already a queer film icon for penning and starring in the beloved Hedwig and the Angry Inch -- had much more on his mind than titillation. Though Hedwig the film debuted in 2001, Mitchell premiered the play off-off-Broadway in 1997. Shortbus was his first film post-9/11, and it's a movie that depicts the New York of that moment with beautifully broken accuracy. Mitchell showcases a city attempting to put itself back together while its inhabitants search for new ways to connect and explore their own metamorphoses. Gay/straight, dom/sub, Black/white -- it was a time when identity was no longer viewed as either/or, and fluidity began to emerge. The idea that life is fleeting, so you'd better live it the way you see fit, became an ethos. Fifteen years later, Shortbus -- now being rereleased in stunning 4K by Oscilloscope Films -- feels as contemporary as ever.

Populated by hip indie New Yorkers, Shortbus celebrates the mixing of boroughs, ideologies, and bodily fluids with joy. The film opens with scenes of unabashed visceral pleasure. In one, a nonsexual domination is delivered by Severin (Lindsay Beamish). The film heads across town to James (Paul Dawson), who is attempting to autofellate himself. Later, he and his partner, Jamie (PJ DeBoy), are in a couples counseling session with Sofia (Sook-Yin Lee), their sex therapist who has her own struggles with orgasming.

After a shocking altercation during one of their sessions, Jamie and James invite Sofia to Shortbus, a weekly salon in Brooklyn. In the case of the film, "shortbus" refers to the idea of being different, a freak, a rebel, a cast-off. Hosted by New York nightlife legend Mx Justin Vivian Bond, with music by the always enigmatic musician Bitch, the salon is filled with women, men, and nonbinary members interested in art and sexual liberation. In one room there are screenings of boring yet important films; in another an orgy is in full swing.

Through the use of diverse, unsimulated sex scenes, Mitchell creates a universal playground for the characters to find themselves. Though queer sex was becoming less alien thanks to aforementioned art-house cinema and even on television -- this was the heyday of The L Word, and the U.S. version of Queer as Folk had just finished its run -- such explicit and introspective depictions were certainly new and thrilling.

That's not to say there aren't tragic moments. The film tackles subjects like suicide, depression, and dissatisfaction, but it does so in a way that's ultimately hopeful and relatable. We follow a character's journey to pleasure, another's feelings of being neglected, another's self-doubt and isolation.

"It really began with a formal challenge: How can I use explicit sex -- real sex -- in a story that wasn't pornographic?" Mitchell says. "It's a medium, rather than a genre. I used sex to tell a story that wasn't about sex. Other films did it, but the ones at the time were very grim." Mitchell wanted something more reflective of his city, humorous but grounded.

"I was seeing porn becoming digital culture, weirdly separating us from each other," he says. "When you've watched porn for years before you've actually had [sex], you approach sex differently. I see Shortbus as an antidote to porn. As an antidote to digital isolation."

While porn presents simulated and perfectly synchronized orgasms, Shortbus shows the truth and the beauty inside the clumsy imperfections of physical connection. Meanwhile, the salon exists as a refuge from urban struggle -- it's a place of learning and acceptance no matter how far our characters reside on the fringes of society. And in these stories exists a specificity and authenticity missing in mainstream film.

"I encouraged [the actors] to talk about an emotional sexual experience," Mitchell recalls. "To let them know we're not just doing a stunt, I want to go deep. We used the auditions as input for their characters' stories, so in a way they wrote their characters, gave them their names, their backstories, and what they wanted in life."

The result is a queer-facing and diverse piece of art that reminds us tragedy can herald creativity, self-discovery, and gratification.

This story is part of The Advocate's 2022 Love issue, which is out on newsstands now. To get your own copy directly, support queer media and subscribe -- or download yours for Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes