A vintage typewriter, a protest sign, a string of pearls, a disco ball -- these are a few of the props arranged to evoke a queer past on set for a photo shoot in the Los Angeles suburb of Culver City with photographer MaryV photographing exclusively on the Google Pixel 6a. The objects pay homage to LGBTQ+ people who were never given their due --unseen in history -- but whose contributions to queer life are immeasurable. Those who have never had a major motion picture made of their lives the way Oscar Wilde, Truman Capote, Harvey Milk, and Elton John have. The overlooked heroes (often people of color) denied their full stories or who the broader culture wasn't quite ready to acknowledge in their own times. These unsung queer ancestors feel almost present, as if they were joining us in spirit and not just in the hearts of the artists and activists gathered to evoke their essences.

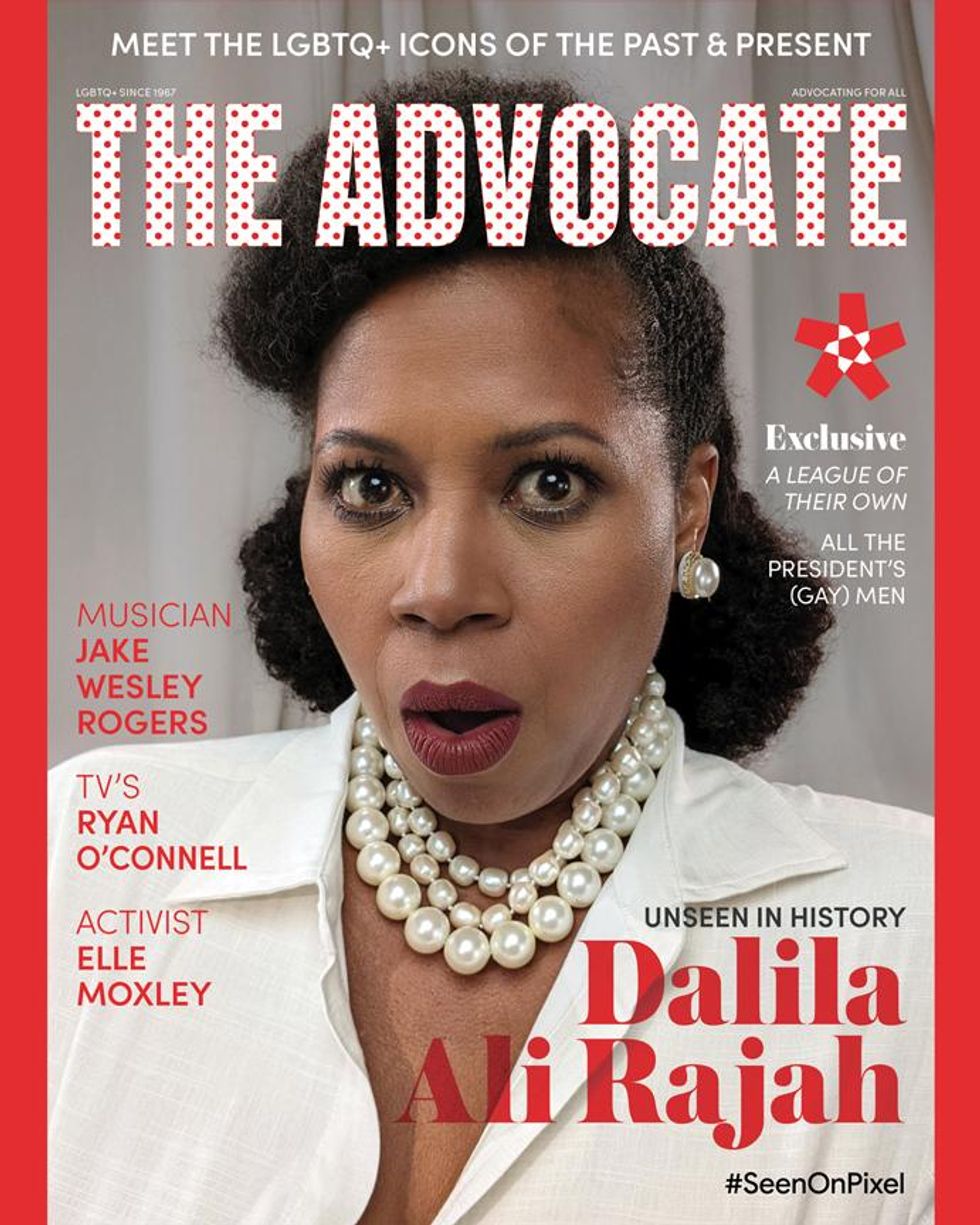

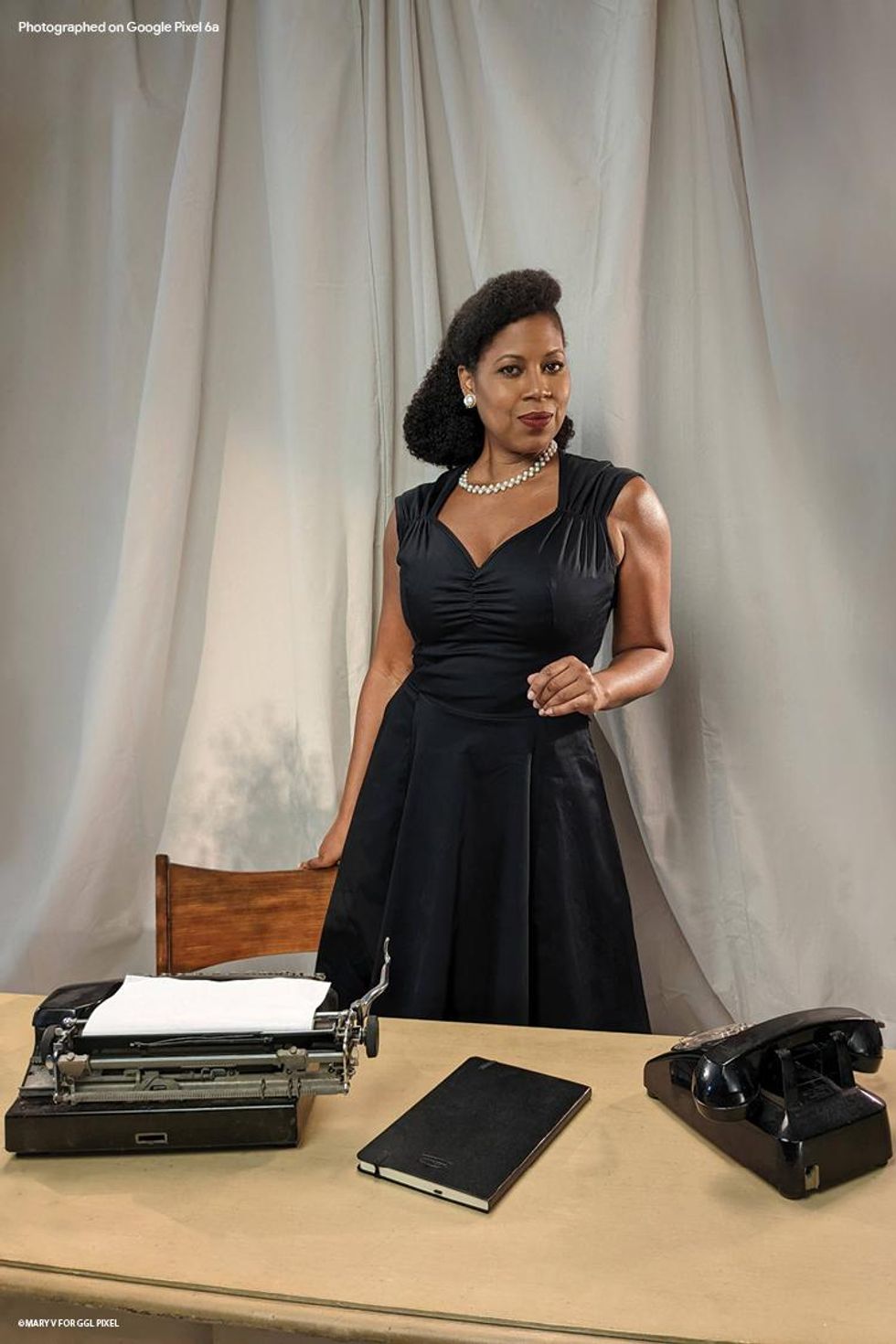

On set is Elle Moxley, founder and executive director of the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, which protects and defends the rights of Black trans women. Sporting faux fur and metallic eye shadow is musician Jake Wesley Rogers, whose glam rock style and queerness is both symbol of the future and a throwback to '70s androgynous rock giants. In linen suit jacket and glasses is Special creator and star and Queer as Folk star Ryan O'Connell, who recently penned his first novel, Just by Looking at Him. In pearls and a mid-century era dress is actor, writer, and producer Dalila Ali Rajah, who is the curator of the Black Queer Joy handle online. She's also a "witch," a "fairy," and a "mommy." They've assembled to recall queer history, remembering LGBTQ+ trailblazers. They each have a person in mind they're hearkening to. They've arrived from various backgrounds, but there's a consistent lens through which they view queer history: storytelling.

"Storytelling started as a part of ritual. Performance was a part of ritual for people and creating routines and resilience," Ali Rajah says. "We carry through the power of ancestral things and preserving the slices of what's happening or whatever's in the zeitgeist or our heart and the authentic moment. It gives us a throughline to especially queer storytelling, Black storytelling -- a throughline from our history to how far we've come, and allows us to know that we've always been here. We always will be here."

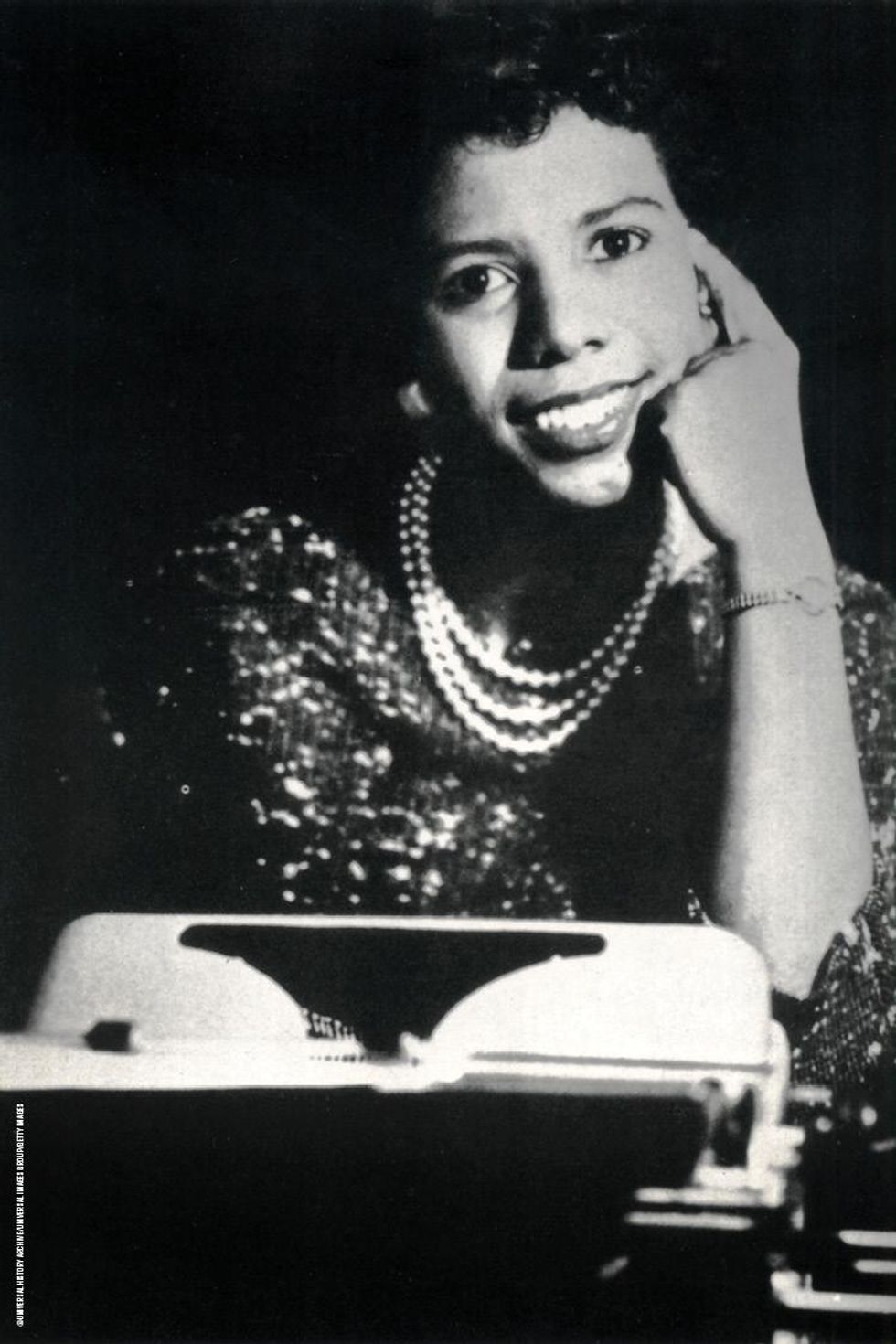

A producer who created Cherry Bomb, a talk show by and for women-loving women in the late aughts, Ali Rajah also writes stories at the intersections of Black and queer identity. Ali Rajah is moved to embody playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the first Black woman to have a play on Broadway. She's famous for writing an essential work about Black Americans, 1959's A Raisin in the Sun, but less known for being queer.

Dalila Ali Rajah

"Thank you for living this life and still writing and getting stories out there, even though it was so hard," Ali Rajah says of Hansberry. "That she, as a bi woman, was able to still find her way to telling stories about the Black experience in ways that the world could receive them.... I'm sure that she couldn't always put everything in it that she wanted to put in it, but if she hadn't [planted] those seeds and lived her life, I couldn't sit here. I just have so much gratitude."

Playwright Lorraine Hansberry

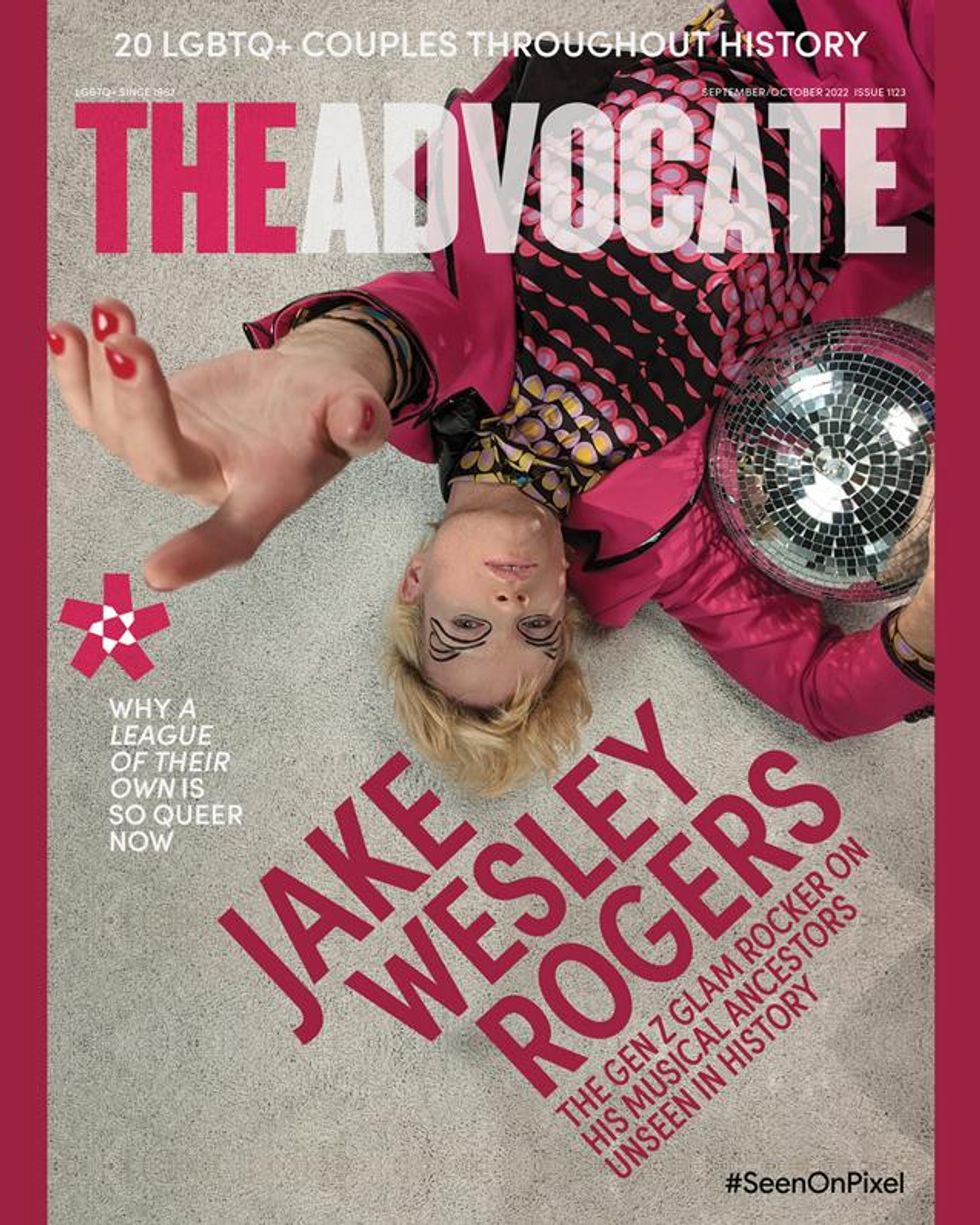

Watch Missouri-born Rogers perform, and he instantly evokes queer rock gods David Bowie and Elton John. On stage, Rogers has singer Jobriath (born Bruce Wayne Campbell) in mind, a glam rocker who lived his gay identity from the outset in the late 1960s and who proclaimed, "I am the true fairy of rock."

Jobriath burst onto the scene in lame jumpsuits and structured costumes that evoked robots and German Expressionist art --precursors to Bowie's looks and Klaus Nomi's style.

Rogers credits his makeup artist, the one behind the fabulous lids he bears at the shoot, with introducing him to the gay glam rocker's music.

Jake Wesley Rogers

"He was so open with who he was," Rogers says of Jobriath. "It wasn't a secret, obviously...we don't really know why exactly we don't know about him, but I have a feeling [his being so out] is probably it. He released...one or two albums...then sort of went into obscurity and died alone," he adds about the artist, who died of AIDS complications in 1983.

"It's tragic," Rogers reflects. "I think a lot of other queer people who were creating [at the] time...Even Elton and Freddie [Mercury] or George Michael, their [queer] love was there in the music -- but it wasn't. There always had to be sort of this coded language."

He adds, "That's something I've really tried to strip away in my music because of people like that, not in spite of them. They opened the door because they paid the price, and people have accepted them so wholeheartedly now. That's the thing with queerness is when something is successful, they don't question it."

Rogers feels a kinship with Jobriath, half a century after he shocked TV audiences with his unabashed queerness.

Jobriath

"Jobriath was 50 years ago, and I'm still kind of feeling a similar thing. I'm still sort of feeling like, if people don't know who you are, and you're also different, then it's probably going to be a bit harder," the "Middle of Love" singer says. "But that's what I'm here to do. I'm here to tell the truth. I won't stop doing that."

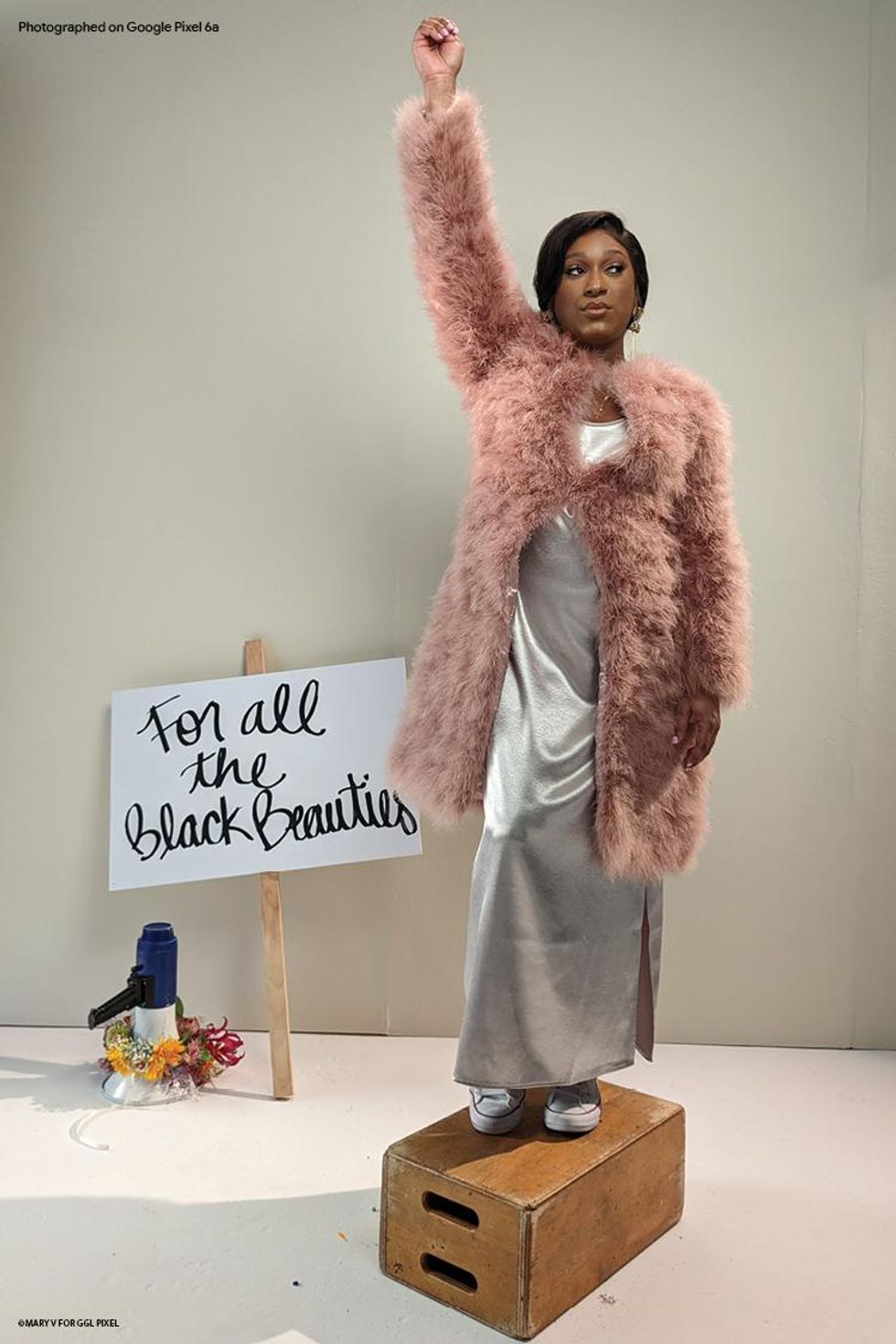

Elle Moxley is the founder and creator of an organization centering Black trans women; she's also an artist and storyteller. Her short film Black Beauty played at Outfest in Los Angeles this summer. Through promoting the film, Moxley realized she'd been telling her story more often, noting it's part of a continuum of similar experiences.

"There are so many memories that come up for me around witnessing other people standing in the fullness of their power and also just so many experiences that I've had that led to my activism," Moxley explains.

Elle Moxley

"I really think it was the introduction to my mother's resistance to my identity that led me to wanting to not only advocate for myself but to advocate for others."

When his series Special dropped on Netflix in 2019, the brilliantly irreverent Ryan O'Connell made inroads in queer storytelling with a tale personal to him by centering a gay leading character who was, like him, living with cerebral palsy. An actor, screenwriter, and novelist with a singular voice and sense of humor, O'Connell likes to nod to author gay authors. He points to Truman Capote as an audacious cultural commentator and also to novelist Andrew Holleran, who captured the halcyon days of gay life in 1978 with the pioneering Dancer From the Dance.

"I read Dancer From the Dance in college, which was major," O'Connell says.

Holleran, an original member of the Violet Quill, is still writing today at 78. His latest novel, The Kingdom of Sand, was released this summer and follows a narrator impacted by the AIDS epidemic. Gay literary giants from E.M Forster to Gore Vidal and Armistead Maupin have been widely celebrated, but Holleran still deserves more of the spotlight than he's been given.

Ryan O'Connell

O'Connell also adds that his earliest awareness of queer sensibility was Ryan Murphy's first series, Popular.

"There were these two characters, Mary Cherry [Leslie Grossman] and Nicole Julian [Tammy Lynn Michaels], who essentially were gay men but dressed as teenage high school mean girls. It was the first time I really understood that there was a queer sensibility and that there was a queer sense of humor," O'Connell says. "Then, reading Susan Sontag's Notes on Camp was elucidating for me. I was like, OK, that's my personality. That's my sense of humor."

Like Holleran's work, O'Connell's humor in storytelling is consumable and radical as it pushes forward visibility for those largely left out of queer history.

Andrew Holleran

"I feel inherently that I'm not a political person. But I feel [that] because I have the self-esteem of a mediocre straight white male, people labeled me as political or as an activist because I'm taking up as much goddamn space as I want," O'Connell says with wry humor.

The writer and actor explains, "When it comes to talking about the experience of marginalized people, I feel like historically, the work has been capital L literary -- very serious, very highbrow, very 'we won an Oscar' vibe. My work is more commercial and poppy," he says. "But because I'm talking about things that have not really been explored, and because of systemic oppression, I've been pushed out of the conversation. [The work] gains more weight, and I really do appreciate that."

O'Connell adds, "I still contend that no one gives a shit about disability. And so it's a little frustrating to see that disability hasn't really entered the chat the way that I think it should. My hope is that conversations around disability deepen and more disabled creators are allowed to make things."

Stories about the why of Stonewall have circulated for decades: Queer people were sick of police raids and fought back or maybe the gays rose up on the day of Judy Garland's funeral. In 2015, Roland Emmerich's Stonewall depicted a white gay cisgender male protagonist throwing the first brick, a gross appropriation of a moment that wasn't his. It was the outcasts, the trans people, LGBTQ+ people of color, and drag queens who were integral to kicking off the queer liberation movement. It's only recently that pivotal trans women like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera have been recognized for their contributions. Honoring Johnson's legacy in LGBTQ+ history, Moxley launched the Marsha P. Johnson Institute in 2019.

Marsha P. Johnson (left)

"I was not alive when Marsha emerged as an activist," Moxley says. "I think so much about how her legacy has been erased from an understanding of who we are as people. It's something that I certainly relate to; to do such great work and to be so giving of yourself and to interact with people who could care less about your contributions to the world is something I understand on a gut level."

Moxley helped organize the first-ever Movement for Black Lives Convening, held in Cleveland, and later helped create the official Black Lives Matter network. She says, "Marsha P. Johnson was a reference of hope for me as I was organizing the largest movement of our time, to be not only reflective of the experiences Black people were having with the police but to be reflective of the experience that all Black people were having with systemic and structural violence. Marsha P. Johnson has always been a symbol of hope for so many, but what I learned...about Marsha is that she was her own, and she did whatever she wanted to do."

At a moment when it feels like hard-earned rights could disappear overnight and leave us reliving history (like echoes of our queer and trans ancestors), Moxley reflects on our activist roots. "Stonewall and the rebellion took a particular journey because there was a need to create a movement that was built around assimilation and separation with the goal of some people being able to achieve what they thought would [then] be applicable to all people."

But, she says, that's not what happened. There are people who were left out. "We had marriage equality, but then we started having the most recorded murders and violence against trans people on record."

Moxley calls to Black trans women like Tiffany Edwards and Muhlaysia Booker, who were murdered and whose stories may never be properly told. "I think it's so important to study history but to also know that we will never ever be able to obtain anything without obtaining everything for all."

We can't forget the struggle and how we got here. But joy is also crucial to our survival. It's hard to persist, let alone thrive, without it. Ali Rajah recalls photos she once saw of Hansberry and the towering Black gay literary figure James Baldwin dancing, their heads tossed back in laughter.

"There's a lightness to the way that they were playing," Ali Rajah says. "It just reminds me that when [they were] in all of that fight and all that turmoil and the Jim Crow South, and [they] were still throwing down and having parties and toasting things and chilling and having interesting conversations."

She adds, "You are not going to take our joy. It is our fucking superpower. And no matter what you do to us, our joy will not be stolen."

Joy is central to O'Connell's work as well. His ability to laugh at himself helps provides solace and release for those whose stories are yet to be told.

"I really just want to make things that are for people like me because there's such scarcity. I feel like the driving force for my work is sort of things that would serve as a balm for younger me that would have saved younger me thousands of dollars in therapy."

Rogers hails from a religious upbringing and finds joy in reframing Bible stories in a way that speaks to queer people. The video for his song "Momentary" reimagines the resurrection narrative and calls to queer luminaries including Johnson.

He wonders about people erased from the Bible and religion, "What does that do to people, especially because these stories are so often used to exclude people? When really, I think they are some of the most beautiful stories about the human experience."

Rogers adds, "[These stories] were framed wrong from the get-go. I'm going to reframe it...so it's authentic to me."

Moxley says joy has been hard to come by sometimes outside of her work and the capitalistic idea that work defines you. But joy is indispensable in the fight for equity. "We won't be able to win any war without joy," she reflects. "That's an essential part of winning, is being able to be in love and joyful about what it is that you do and who you're doing it with."

PHOTOGRAPHY by MaryV; PHOTO ASSISTANTS Lance Williams, Jin Jin; LIGHT TECH Sebastian Johnson; DIGITECH Merlin Viethen(@merlin_vino); STYLIST Edwin J. Ortega(@edwin.j.ortega); STYLIST ASSISTANT Brooke Mumford[@brookesquad]; MAKEUP Darian Darling(@moidariandarling); MAKEUP ASSISTANT Daniel Coronado(@danielitorock); HAIR Allie Ellis(@allieellishair); HAIR ASSISTANT Andy Trieu(@andyhtrieu); MANICURIST Holly Falcone(@hollyfalconenails); PRODUCTION & CREATIVE DIRECTOR Tim Snow(@snowmgz); PRODUCER Stevie Williams(x2production.com/@beingstevie); CREATIVE CONCEPTION Stuart Brockington, Anna Carias, Tim Snow, Tracy E. Gilchrist; SET DESIGNER Dylan Lynch; SET ASSISTANTS CJ Keossaian, Kellie Marie; VIDEO Austin Nunes(austinunes.com/@austinunes); CATERING Beezoo(@beezoo.la); STUDIO Smashbox Studios LA(smashboxstudios.com); ELLE'S TEAM PUBLICIST Yanira Castro; SUPPORT Reyna Castro; HAIR Brian Anderson; MAKEUP Marquis Ward

This story is part of The Advocate's 2022 History issue, which is out on newsstands August 30. To get your own copy directly, support queer media and subscribe -- or download yours for Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes