Rustin is all about history. The Netflix biopic centers the story of Bayard Rustin, a key organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. During Rustin’s lifetime, his vital contributions to the Civil Rights Movement were underplayed and erased due to his sexuality. But the film, directed by George C. Wolfe and starring Colman Domingo, beautifully restores Rustin’s place in the history books as a Black leader who was also proudly and openly gay. Today, Rustin is also making history as the first major studio film to have a director, star, and writer who are all Black queer men. Julian Breece (When They See Us) wrote Rustin’s story and cowrote the screenplay alongside Dustin Lance Black (Milk). Breece spent years working on the project, conducting hours of interviews with loved ones and Rustin’s surviving partner, Walter Naegle. Ahead, he shares his insights into his process and the relevance of Rustin’s story today.

How did you first learn about Bayard Rustin? And what impact did knowing his story have on you as a Black queer man?

I wish I could say I learned about Bayard Rustin in one of my high school classes, but I didn’t. I came across his name when I was researching a paper on the Civil Rights Movement. There was only a brief mention of his work and his sexuality. But just seeing a photo of him and knowing that an openly gay Black man was a prominent figure in the Civil Rights Movement had a huge impact on me as a teenager who was still coming to terms with my own sexuality. I was struggling with the same anxieties that so many LGBTQ+ young people encounter — from fears of isolation to physical danger. Knowing that Bayard was Black and out in the 1930s, ’50s, and ’60s — times that were hostile to both ways of being — didn’t make my fears disappear, but they certainly put them into perspective. I didn’t have any gay role models in my physical environment, so men like James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin were my early heroes.

What key revelations about Rustin and his story did you unearth in your research?

In my early research for the film, I learned that Bayard and Dr. Martin Luther King were colleagues in the Civil Rights Movement. But when I started interviewing people, I learned that the two men had a deep, intimate bond that changed the course of history. Today, King is synonymous with civil rights and non-violent resistance, but most people don’t know that Bayard was his closest advisor and mentor. Bayard introduced King to Gandhi’s pacifist teachings and he was the brains behind King’s grassroots organizing strategy. Here you have King — the most famous man of God next to the Pope — being taught by and having an intimate friendship with a gay man. To the point where rumors started swirling, and King and the movement were forced to distance themselves from Bayard. I found the tension between those two to be remarkable and exciting, so it became the main conflict of the screenplay.

Since you’ve started this project, the U.S. has seen a push among conservatives to censor media and education related to Black and LGBTQ+ history. How has modern-day politics influenced your view of Rustin’s story as well as the role of your own production in the world right now?

I was invited to see George’s early cut of the film, and I remember it was around the time that Florida had just expanded its book ban. When I was sitting in that screening, I got chills when I realized just how relevant the story is. Bayard believed that any censorship of the truth is violence, and the battles Black and LGBTQ+ people have fought in this country have been marked by the same censorial violence we’re up against today. The physical violence against us — the lynchings, terror campaigns, and assassinations — were the desperate, pathetic methods used to shut us up and deny the truth of our humanity. If they don’t silence us, they’re afraid that people will continue to see that we’re productive members of society who deserve equal power and authority. Bayard was erased from the history of the Civil Rights Movement because in order for Black people to be seen as full humans in the country, we had to contort ourselves into the mold of white patriarchal respectability, and Bayard simply didn’t fit. Bayard’s story is powerful because we can link his work to triumphs in the fights for Black equality and LGBT rights. But history’s treatment of Bayard makes you wonder — with everything we’ve gained with those movements, what and whom did we sacrifice in the process?

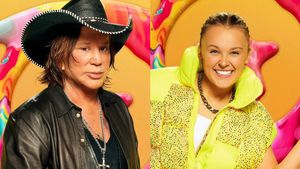

'Rustin' screenwriter Julian Breece (photo by Colton Haynes)

'Rustin' screenwriter Julian Breece (photo by Colton Haynes)

What can LGBTQ+ people learn from Rustin in the fight today for equality and dignity?

I think what we can learn from Bayard is his audacity to be seen. He was a tall, distinguished man who carried himself with an almost aristocratic air about him. And that was all by design. Bayard wanted to stand out from the crowd and grab people’s attention. He demanded to be seen, heard, and respected, and even if his audience didn’t meet those demands, he didn’t make himself smaller. There were times in in nonviolent sit-ins when Bayard would get beaten bloody by white racists but stand back to take more hits until he couldn’t stand anymore. He knew that even if they were effective in silencing him, his audacity had made an impact. LGBTQ+ people in this country are under direct attack right now by the far right. Their goal is to create a chilling effect amongst us. They want us to feel so unsafe and isolated that we silence ourselves, run, hide, or conform. I think Bayard would encourage us to stand up, get loud, and take up space. This is our country too. We deserve to claim it, and they need to hear us claim it.

This is a biopic of a Black gay figure where the director, star, and cowriter are all Black gay men. How do you feel about being a part of such a milestone for Hollywood?

It’s incredible. I could be wrong, but I think this may be the first time three gay men of any race have had those roles in a major studio film. Which is pretty mind-blowing and makes me feel even more privileged to be a part of this film. I’ve been a fan of George and Colman for years, and I’ve looked up to them as Black gay men in the film industry who’ve been able to achieve high-level success. Most people don’t know how close to impossible it is for queer people of color to make it in Hollywood, and that’s not changing as quickly as it should. Fifteen years ago, a studio wouldn’t have hired three Black gay men to write, direct, or star in this film. But this film is proof that we have made progress, and I’m grateful that Bayard’s legacy and the legacy of the March have been memorialized with George’s beautiful film. George, Colman, and I are all bonded by a deep sense of personal duty to Bayard, his partner Walter, and the activists who worked to make the March on Washington a success. If this moment is historic there’s beautiful irony it. Bayard was erased from history for being an openly gay Black man, so I think he’d be pleased to know that three out and proud gay Black men helped bring his story to the world.

Is raising visibility of underrepresented groups, as well as the battles they face, important to you as a writer in Hollywood? Tell us what motivates you.

Most of the film and television projects I’ve written are centered on or include LGBTQ+ characters of color. I don’t think about it as raising visibility in a political sense, even though the outcome is often viewed as political. And I love that. When I write those characters, it’s because they’re a reflection of my reality and my worldview, and I believe that worldview is just as valid and important as any other. When I was growing up, most of the movies and TV shows I saw were written by, produced by, and starring white cisgender men — even the ones about gay characters. Some of those shows were great, but they had glaring blind spots. I became a filmmaker because I wanted to create work that filled in those gaping holes in the narratives I took in as a kid. Feeling erased and left out made me want to throw in my hat and join the larger cultural conversation. I’m a queer Black man with queer and trans people of color playing lead roles in my life, but that doesn’t mean my point of view can represent all people of color, or queer people, etc. That’s why it’s so important for the industry to attract and nurture as many diverse voices as we can. Visibility is a process that never ends, and it starts with creators.

What have you learned from writing about Rustin?

If writing about Bayard’s life taught me anything, it’s that being Black and queer in America makes us the ultimate outsider-insiders. We possess the same double consciousness that W.E.B. Du Bois described as the feeling of being distinctly American while feeling forced to perceive oneself through a lens of whiteness. Our queerness adds yet another lens to that toolbox, giving us access to a unique bird’s-eye view of the social order in this country and our place within it. For Bayard, that dynamic way of perceiving the world proved to be a superpower and a curse. Bayard’s strategic genius didn’t spring from his years of experience as an organizer or formal study, it came from his deep empathy for humanity and his ability to see people’s fears and needs without judgment.

Rustin is now streaming on Netflix.

'Rustin' screenwriter Julian Breece (photo by Colton Haynes)

'Rustin' screenwriter Julian Breece (photo by Colton Haynes)

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4