He was an immigrant from a small town in Australia who became an Oscar-winning costume designer. He was an openly gay man in Hollywood when few dared to be out. And he may well have been Cary Grant's boyfriend.

All those statements pertain to Orry-Kelly, the subject of Gillian Armstrong's new documentary, Women He's Undressed. Using dramatic re-creations, interviews, and archive footage, it portrays the designer's bravery, honesty, and artistry, including his costumes for stars such as Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca, Rosalind Russell in Auntie Mame, Marilyn Monroe in Some Like It Hot, and Bette Davis in Jezebel, Dark Victory, and Now, Voyager.

Yet Armstrong, the director of My Brilliant Career, Little Women, and other acclaimed films, knew nothing about Orry-Kelly when producer Damien Parer approached her about helming the documentary. "I asked, 'Who's Orry-Kelly?'" she says.

Armstrong, working with writer Katherine Thomson, soon learned much about her fellow Australian and his brilliant career, plus classic Hollywood films in general. "It was a great education for me," she says, explaining that when she went to film school in the 1970s, Hollywood studio movies from that era -- roughly the 1930s through the 1950s -- were out of favor among academics.

Armstrong and Thomson consulted Orry-Kelly's letters and film histories. They interviewed friends and associates -- among them actresses Angela Lansbury and Jane Fonda, Eric Sherman (son of director Vincent Sherman), and Scotty Bowers, who famously arranged sexual liaisons for Hollywood stars. They talked to critics and historians, such as Leonard Maltin and William J. Mann, and costume designers, including Ann Roth and Catherine Martin. And toward the end of their research, they discovered an unpublished memoir by Orry-Kelly himself.

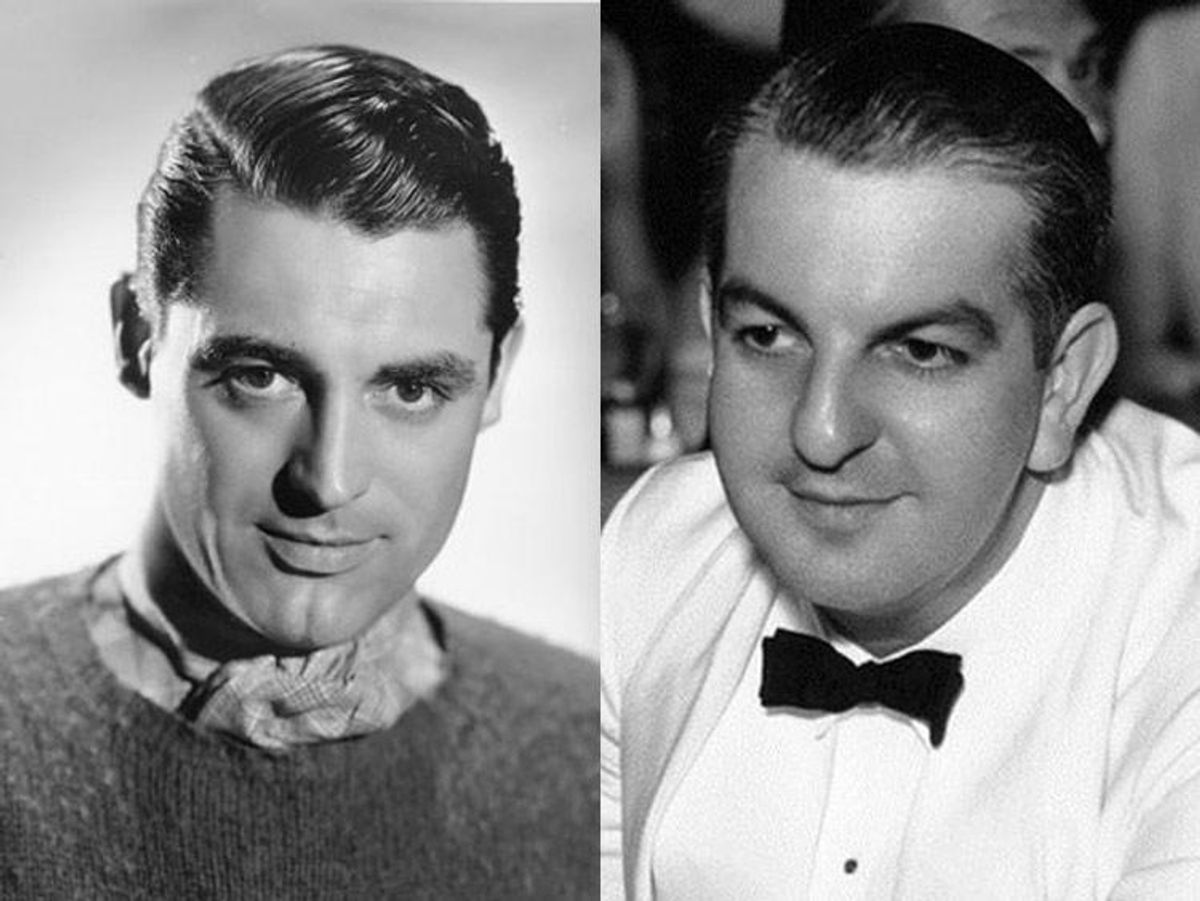

The designer was born George Orry Kelly in the small town of Kiama, Australia, in 1897. At 17 he moved to Sydney, then a few years later to New York City. There he made a living selling hand-painted shawls and ties, and he met a breathtakingly handsome fellow immigrant -- a penniless young man from Bristol, England, named Archie Leach, destined for movie stardom as Cary Grant. They lived together off and on for nine years, and both eventually made it to Hollywood.

Armstrong notes that we can't know for sure about anyone's sex life, but the film provides ample evidence that the two men were more than friends. It also covers Grant's later, well-known liaison with actor Randolph Scott before Cary went on to the first of his five marriages. And according to the film, once Grant became a star, he pretty much cut Orry-Kelly out of his life -- something the designer resented deeply.

That doesn't speak well of Grant, who remains beloved by millions of fans 30 years after his death and 50 years after he made his last film. But Armstrong offers a bit of understanding, if not an excuse. "Cary was a victim of his era," she says, as there was great pressure on stars to appear completely heterosexual. At that time, being in a same-sex relationship was a career-killer -- it certainly ended the career of Billy Haines, a star of the silent and early sound eras, as he would not give in to studio demands that he leave his partner. And there were even more dire consequences for being gay, like being blackmailed or arrested.

There was pressure on behind-the-scenes personnel as well. Top gay costume designers Travis Banton and the single-named Adrian yielded to it, entering into marriages of convenience, the film notes. The closet meant job security.

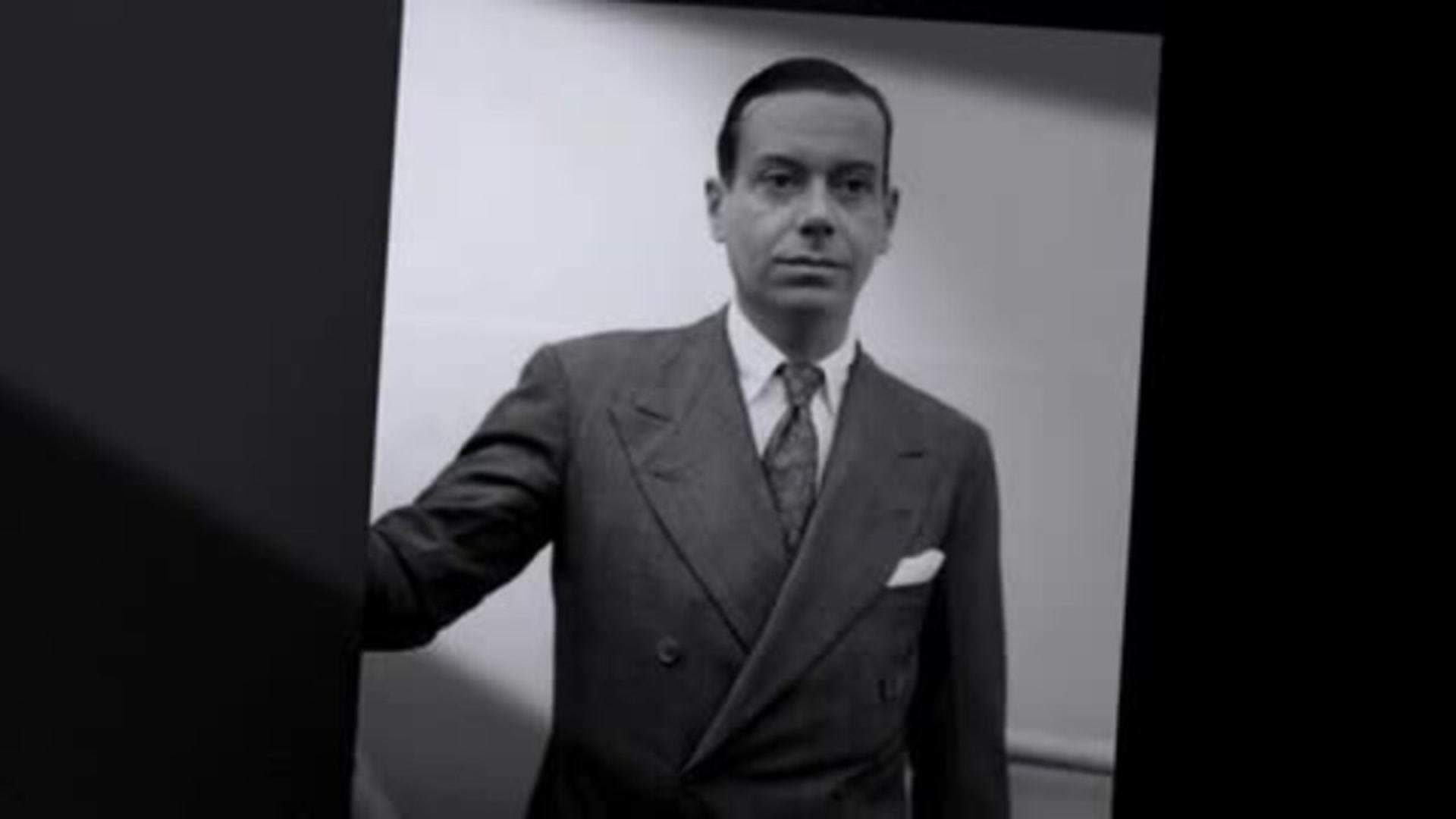

But the closet was not for Orry-Kelly, and he managed a stellar career just the same. "It was really quite brave" of him to be openly gay at the time, Armstrong says. It didn't hurt that he was close friends with Ann Warner; her husband, Jack, headed the Warner Bros. studio, where the designer ran the costume department from 1932 to 1944. It also didn't hurt that he had cordial relationships with powerful gossip columnists Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper, who could make or break anyone in Hollywood.

None of that would have helped, though, if Orry-Kelly didn't have incredible talent. He created the dazzling and often risque costumes for the dancers in the visually stunning musical numbers in director-choreographer Busby Berkeley's films. In Casablanca, he showcased Ingrid Bergman's beauty with simple but elegant clothing that made her character the world's best-dressed refugee. Late in his career, with Some Like It Hot, he won his third Oscar thanks to his see-through, strategically beaded dresses for Marilyn Monroe -- as well as the costumes in which Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis disguised themselves as women.

He excelled at making his costumes fit the story's needs -- Lemmon and Curtis, for instance, had to look at least somewhat believable. And he could go glitzy or plain, depending on what the scene called for. In Now, Voyager, he took Bette Davis from ugly duckling to glamorous swan, but in the final, intensely emotional sequence, she's dressed in an understated blouse and skirt so as not to detract from the drama.

Orry-Kelly tended to work collaboratively with actresses, and he had a particular rapport with Davis, who was unafraid to look unattractive if it suited the character, such as in the gaudy frocks she wore as a fading beauty in Mr. Skeffington. He also designed her famous dress for Jezebel -- in which she appears, scandalously, in a red gown at a ball where the women were specifically asked to wear white. It worked even in a black-and-white film.

The designer's career had its downs as well as ups. He was a heavy drinker who didn't suffer fools gladly, and these factors likely contributed to his firing from Warner Bros., although he says in the memoir, "Jack Warner eventually said I could stay even if I am a mean drunk." His drinking finally led to a stint in rehab, during which all but a few friends deserted him, but he bounced back and kept working almost up to his death from cancer in 1964.

The Jack Warner line is one of those read by actor Darren Gilshenan, who plays Orry-Kelly in the documentary's dramatic re-creations. "I actually hate dramatic re-creations in documentaries," says Armstrong, but she decided to include them in this one as a way to use the designer's own words, drawn from the memoir and his letters, and showcase his wit. Some examples of this wit: He says director Michael Curtiz, with whom he sparred over costumes for The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, probably "researched the Elizabethans on the john." And he says he made "a few mistakes with Miss Monroe, like telling her Tony Curtis had the better ass."

"He had this self-deprecating wit, but you really got the feeling that he hated hypocrisy and hypocrites," Armstrong says. She hopes that will be one of the takeaways from the movie as well as "what a great master he was" and an understanding of the art of costume design. "It's a wonderful story," she says, "about resilience and survival and integrity."

[RELATED: The Iconic Looks of Orry-Kelly]

Women He's Undressedhas been shown in several film festivals and is now playing at Los Angeles's Arena Cinema. It's available on DVD from Wolfe Video. Watch an exclusive clip below. His memoir, Women I've Undressed, has now been published in Australia and is available as an audiobook in the U.S.

Watch an exclusive clip from the film below.