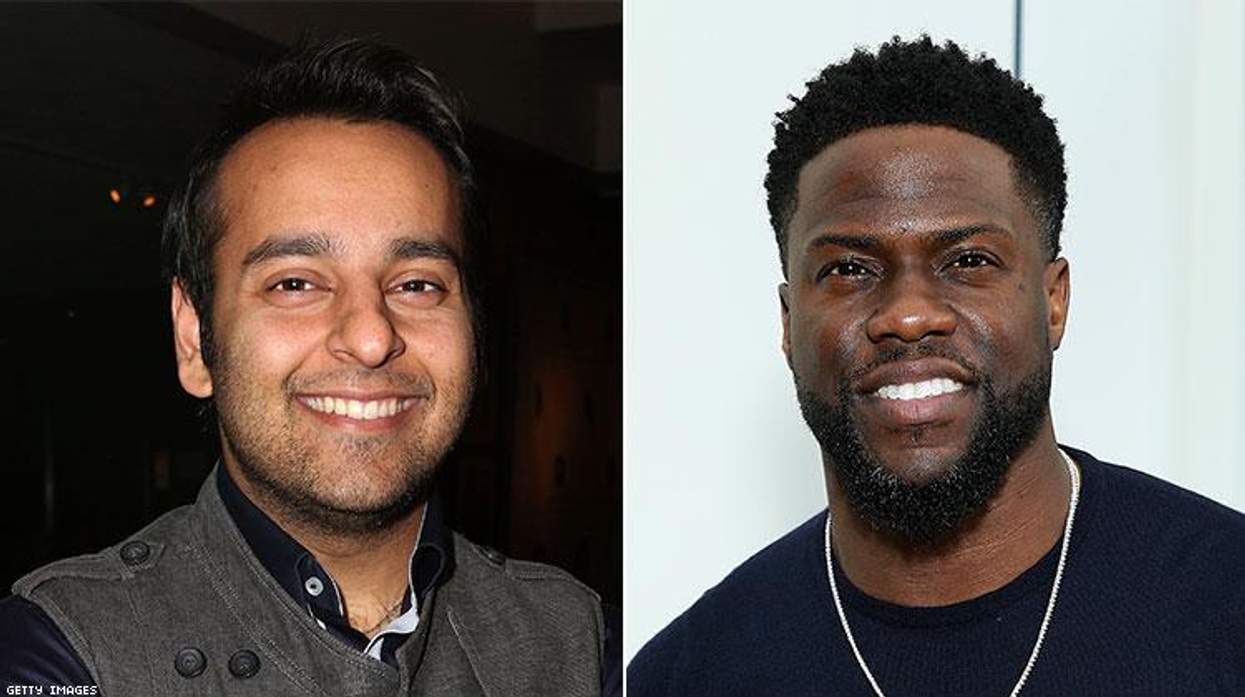

On Thursday I woke up to the news that Kevin Hart was producing and acting in the Monopoly movie directed by Tim Story for Lionsgate and Hasbro. The news had particular resonance for me because the game was especially close to my heart as a kid (as it must have been for countless others). Also, I wrote the screenplay for the movie when it was at Sony Pictures (with Hasbro, Emmet/Furla and Scott-Free attached to produce).

The news sparked mixed feelings in me. Given the recent kerfuffle over Hart's history of antigay tweets, is he the right man for a film about the most recognized game brand in the world, cherished by millions, an icon of people's childhoods the world over?

It takes a brave team to take on something so cherished and iconic. Adapting Monopoly comes with the turf -- the ridicule of making a movie out of a game with no evident narrative, whose lead characters are all made out of lead.

People will no doubt be outraged at the sacrilege. The words "cash grab" will be thrown about. Indeed, the reek of Battleship and the diminishing returns of the Transformers films are hard to shake. Hasbro doesn't "need" to do this; it'll still sell oodles of Monopoly Marvel editions and apps regardless of a motion picture tie-in. Neither is this a merchandising ploy, since a stuffed Old Uncle Pennybags (that's the monocled character's official name) isn't exactly going to be the hot toy of the Christmas shopping season.

So I have to believe Story, Kevin, and Hasbro genuinely want to do this last, untapped piece of iconic IP some justice.

That said, you can't not address Hart's tweets when Monopoly is an integral part of everyone's childhood, especially mine. My particular closeness to it is probably why the company once entrusted the reins to a relatively unknown young writer in the first place.

When the first Gulf War broke out when I was 9, I was displaced from my home in the Middle East to an austere boarding school in the United Kingdom. I was brutally bullied, as I was an "other" in every sense of the word. I was locked up in a school where video games and toys (and phone calls home) were banned but board games were allowed. So, after unsuccessfully attempting to eat rat poison and failing to run away without being caught, Monopoly and Spielberg films are where I took refuge when I was kicked, spat on, "hit over the head," or called a "Paki" or a "fag" or "wet." Monopoly became my safe place. For a couple of hours, I could take back the power; I could own my own house, street, or even a metropolis. And it took me back home every time. Pennybags (and Spielberg) literally saved my life. So for me, Monopoly was personal. And it still is.

I remember trying to convince the powers that be at Hasbro of this; that the emotional power of Monopoly wasn't an appeal to our worst angels, but drawn from something else. I showed them a magazine ad for Monopoly from the 1960s of a family sitting at a kitchen table playing the game, captioned "Mother cleans up again!" and asked why this ad worked - because Mother, who wasn't the breadwinner in this tableau (and was literally confined to the kitchen to play Monopoly in her apron), had the last laugh. She beat the one who wore the pants at the table.

Monopoly was a great equalizer. You see, in the game, everyone starts with the same amount of money; far from being an exercise in Trumpian capitalism, it is actually a kind of socialist experiment. It doesn't matter if you're female, smaller, darker, poorer, younger, or queerer, anyone can win (herein lies its enduring appeal to kids). In fact, this is how Monopoly was originally conceived. First envisioned by a woman, a Quaker (when it was called the "Landlord's Game"), and then transformed into the Monopoly we know during the Great Depression by a penniless inventor from Atlantic City called Charles Darrow, sketched out on a tablecloth so his kids could role-play fantasies of power when they had none.

In 2013, I had just come off a project for trailblazing director Kimberly Peirce (Boys Don't Cry) where I was told by a very senior executive of a certain company to keep my mouth shut in the presence of the studio head because I "didn't look or sound like the kind of person who could write this." So when a senior executive at Sony and a producer at Hasbro took a chance on a young writer of color (before it was commendable) on a PG, Amblin-esque throwback script (before Stranger Things made it viable), it felt like kismet. For two years I gave my all to the project. Any less and I wouldn't be doing my 9-year-old self justice. I traced the streets of Atlantic City. I researched the origins of the tokens. Bought every version of the game. (Did you know there was an unlicensed "Gayopoly" in the 1980s with handcuffs and stilettos as tokens? Or a missionary "Bibleopoly" with churches instead of hotels?)

The script was about a sensitive, bullied kid from crumbling Baltic Avenue. Surrounded by dream-smashers, he is over-attached to his childhood and embarrassed by his closeness to his best friend, whom he is about to lose due to the gentrification of the neighborhood by a corrupt developer. He discovers that the inventor of Monopoly hid clues in the illustrations on the original Chance and Community Chest cards we've been playing with since 1935, which lead him and his diverse crew on a chase across the real-life streets of Atlantic City -- through abandoned underground railways, grand old hotels, the Boardwalk and more -- to the fortune Darrow left behind, all while being pursued by a painfully insecure, bankrupt real estate scion. In the process, they will discover that even if the world wasn't designed for them, by sheer perseverance and belief in themselves, they could still make it.

The explicit message of this screenplay (other than the obvious "money doesn't buy you happiness") was one of empowerment. Heck, even the Fed prints money (so it's all Monopoly money, isn't it?), so let's take the power back. You don't have to live by the rules someone else created. You can play your own game. You define who you are and who you can be -- and anyone can win.

Sadly, the week the script was to go to Amy Pascal -- then the head of Sony Pictures Entertainment -- for a green light, the infamous North Korean "Sony hack" happened. The subsequent upheaval and new studio head meant projects were abandoned and properties like Monopoly were passed off to other studios like Lionsgate. Pascal ultimately resigned for unfortunate things she had written in private emails, and now here we are, a few years later, when the new guy being handed the reins is also under fire for saying regrettable things (this time on a public platform).

Now, Hart seems like an embodiment of that very idea of egalitarian empowerment that's at the soul of Monopoly. As a self-proclaimed "small black man" from a challenging family background, he has become a household name and an internationally bankable star in a ruthless and often racist industry. A studio has just given the reins of a potential franchise and its most famous property to Hart and Story, a pair of creative collaborators of color. We'd be remiss not to celebrate the importance of that achievement.

But then there are those darn tweets. Hart has apologized-ish multiple times for the particular brand of bigotry he was peddling as humor at the time. But the media - and the Academy -- just won't cut him a break, or so he feels. "Standing [his] ground" on Instagram, Hart declared, "I've moved on - I'm in a completely different space in my life." Indeed, those tweets were from almost a decade ago, and the ancients say we grow in seven-year cycles, so I'd like to believe Hart has evolved. The problem is, the world hasn't; what he's missing is that this isn't about Mr. Hart. Now that he has become the accidental poster boy for black homophobia, toxic masculinity, and abusive parenting (regardless of whether that characterization has any merit in terms of who he is today), the continued outrage stems from the fact that something needs to be done about the underlying psychology of those tweets that's still prevalent in America and across the world and the feeling that perhaps Hart - as the reluctant nexus of this conversation - needs to step up to the plate to advocate for real change. After all, between Instagram and Twitter, he commands nearly 100 million followers - more than the president (and look what that man can unravel with a day's tweeting alone). In today's world, you either think there are "very fine people on both sides" or you don't. If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.

As the latest guardians of this indelible icon of childhoods the world over, Hart and Story have the power, the talent, and the canvas to make something empowering and transformative out of Monopoly. My Indian parents don't know Transformers, Battleship, or Candy Land, or even who Meryl Streep is (true story), but they know the Beatles, The Wizard of Oz, Elvis, and Monopoly. The game is sold in 114 countries. Its generational and geographic reach is probably greater than most Americans realize. Because of Kevin Hart, it is likely to be seen in those very communities where toxic masculinity, homophobia, and parental abuse are the most prevalent.

On a recent trip back to the Middle East, down the dustiest alley, the most pirated DVD was the Rock and Kevin Hart in Jumanji. Not so far away, gay men are being thrown off buildings. The heads of sons and daughters are not just being hit but cracked open by disapproving parents. "Dignity killings" are real. So the stakes are literally life or death for young people, however they identify. Those parents may even take their kids to see this movie. Words matter. Stories matter. Isn't that why we make movies?

So, Mr. Hart, can we transform this divisive moment into something positive? Can we use all of this unwanted attention directed at you to educate people about the dangers of bullying, homophobia, and toxic masculinity? Because that suicidal 9-year-old is counting on you. Even though you may be throwing out the script wholesale and starting afresh, when you're re-envisioning the Monopoly movie, will you make something that empowers someone's son or daughter, so they know -- whether its a dollhouse or a house on Boardwalk -- that he or she (or they) can still have it all?

People change. You say you have. That's exactly why it's so important to encourage others to be part of that process. Reality might not come with a "Get Out of Jail Free" card, but in the words of my late mentor, we are revealed not by what we say but by what we do. Show, don't tell. It's the only way to pass Go.

VINEET DEWAN is an Academy Nicholl-winning screenwriter and director who lives between Los Angeles, London, and the Middle East.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes