At a recent event in Los Angeles, a group of Georgian polyphonic singers sang in their native tongue to a well-heeled group of professionals in the film industry. As the performers chanted in beautiful harmony at the airy home in the Hollywood Hills, the sprawl of the world's entertainment capital twinkled behind them.

The performance was in celebration of And Then We Danced, a Swedish-Georgian film directed by Levan Akin that is Sweden's Oscars entry. Guests, having just screened the film, mingled with the cast members and director, and enjoyed cocktails and hors d'oeuvres as the singers performed.

The beatific scene in November stood in sharp contrast to screenings days earlier at the Amirani Cinema in Tbilisi, where hundreds rioted outside in protest of the film. At issue was the subject matter. The production centers on a dancer in the National Georgian Ensemble, Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani), coming to terms with his attraction to another man.

Masked protesters threw firecrackers, burned a Pride flag, and pressed up against a police cordon. About a dozen were arrested and at least one activist was hospitalized as a result of the fray. While none of the screenings were disrupted, the film's run was cut short to only three days due to the disruptions.

"It's so insane that people had to be brave in order to go see a film and risk getting beaten up or even worse," Akin told The Advocate. However, the filmmaker, who is Swedish with Georgian-born parents, contends the protesters reflected a minority opinion toward LGBTQ people within the Eastern European nation, which is unfamiliar with queer representation in media but not hostile to it.

"They scream loudest and they're very aggressive, but I think the major population in Georgia supports this film," Akin asserted.

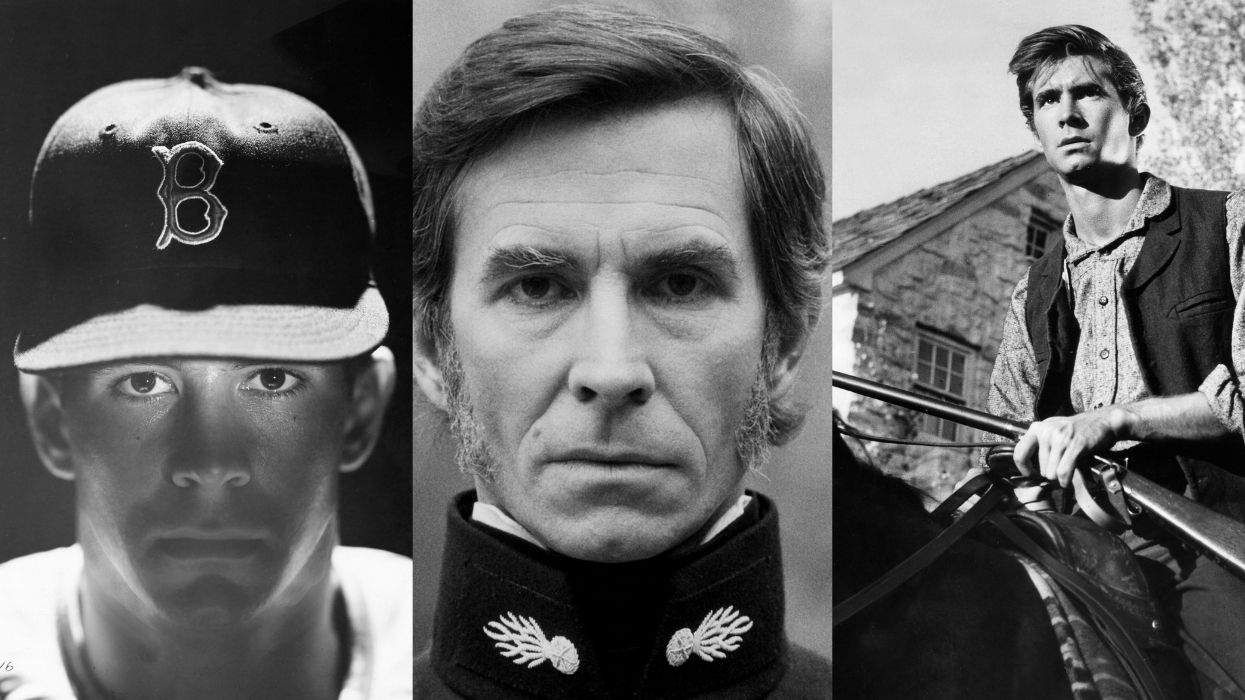

Pictured: Levan Gelbakhiani (Merab), center

Pictured: Levan Gelbakhiani (Merab), center

What got lost in the international headlines were the audience members who turned up in droves to see And Then We Danced, including mothers, fathers, and grandparents alongside their LGBTQ kids. The film sold around 6,000 tickets, having sold out after 14 minutes of being available for purchase online. It was not a lack of demand but the cost of police presence -- about 30 officers per screening -- and weapons detectors that ultimately forced the film's early closure.

One 89-year-old woman -- who like all of the attendees had to pass through a so-called corridor of shame between the police and the yelling protesters -- was flummoxed by the intense reaction to the film. "I don't know why these idiots are outside screaming," Levan recalled her saying.

Regardless, it was an "intense" experience for a filmmaker to watch his production turn into national and then international controversy. Akin woke up one morning with around a dozen missed calls from journalists trying to reach him about the protests. Thankfully, throughout the ordeal, no one was killed or seriously injured.

However, Levan is still reeling that a film honoring Georgia's culture could spark such hatred. "It's such a celebratory film," Akin said. "It's really a film that comes from a place of love. So for that to sort of turn around and become ugly, it would have been really bad."

Behind the scenes of the protests, there were also other issues at play in Georgian politics. Several territories in Georgia are occupied by Russia -- a military occupation following the Russo-Georgian War in 2008. Akin believes the protesters rallying against his film were funded and fueled by Russian forces attempting to sow division.

"There's a bigger political game at stake in that region," Akin said. "And the LGBTQ issue is really Russia's weapon make people afraid of going to the West."

The protesters "claim to protect Georgian culture and tradition," he continued. "If they really wanted to protect Georgia, they'd be screaming at the borders of the Russian guards. But they're not."

And Then We Danced itself was inspired by an anti-LGBTQ protest. Akin recalled how in 2013, while he was working as a filmmaker in Sweden, he watched a news report on YouTube about 20,000 protesters who descended on a rally for what was then called the International Day Against Homophobia, which only attracted a few dozen participants. The counterprotest had been incited by members of the Georgian Orthodox Church. Dozens were injured in the violent clash, in which protesters hurled insults as well as stones at the LGBTQ activists.

"I have Georgian heritage, and I was like, 'Oh, my God, what's going on?'" Akin recalled thinking at the time. "'How can it be this extreme?' I knew that it wasn't easy to be open, but I'd never known it was that bad. So for me, that was really an eye-opener, and I couldn't let it go."

The show of homophobia in his motherland stuck with him. After Akin completed his prior film, The Circle, he traveled to Georgia to do research on a production he wanted to make about LGBTQ lives there -- although he was not sure exactly what the subject matter would be at the time. As Akin interviewed native Georgians, many of them dancers, the topic of folk dance struck him as appealing as a filmmaker.

"When I did research on the Georgian dance companies, they were so masculine and patriarchal. They were so old-fashioned," Akin said. "I thought it was interesting because here in the West, we usually associate dance with a more queer thing, like a lot of dancers are. But in Georgia, it was so masculine. It was almost like they were hockey players. I was fascinated by that. And then I also thought, visually, it was also cinematic because you can tell a lot of emotions through movement."

Finding Gelbakhiani as a leading man also informed the direction of the storyline, which shows how the arrival of a talented new dancer, Irakli (Bachi Valishvili), stirs feelings of both competition and desire within Merab; at the time of their meeting, he is in a relationship with a female member of the troupe, Mary (Ana Javakishvili). Akin trained his lens on Gelbakhiani, a dancer who only had limited acting training in local theater productions, for six months in order to make him comfortable in front of the camera and learn his movements.

Akin also had frank conversations with his cast members about the potentially controversial nature of the queer subject matter. Just as Merab experiences in the film, Georgia is made up of people (usually younger) who are accepting as well as more conservative, intolerant forces. Legally, the nation does not recognize same-sex unions, but it does prohibit discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity. But even understanding this climate, all members of the production were "shocked" by the extreme reaction they met at the opening.

The Georgian government, until the recent protests, has also been silent about the film. And Then We Danced, funded in part by the Swedish Film Institute, is Sweden's submission to the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Film. But Akin and his team had been hopeful that Georgia would have taken on this mantle.

"This is like one of the biggest things to ever come out of Georgia, and nobody in Georgia on the government level talked about it. It was like this movie didn't exist up until the premiere," Akin said. While officials did eventually address the protests, Akin believes it was due to international pressure tied with the country's hopes of becoming a member state in the European Union.

"I would never have been able to make this film had I been a Georgian and living in Georgia," he said.

Regardless, Akin sees hope in how the younger generation has responded to the film, which has been part of a movement advocating for greater freedoms. "This movie really in a way has already moved the pendulum a little," Akin said. Young protesters, while demonstrating for various issues in front of the Parliament of Georgia, have even taken to singing and playing music from And Then We Danced as a display of resistance.

These protests are in harmony with the message of And Then We Danced. Just as his protagonist, Merab, uses dance to stage a protest against oppressive norms, so too does Akin feel responsible as a filmmaker to tackle political issues within his work.

"I think that in this day and age, art perhaps needs to be political in a way. It's not just in Georgia. Look at Poland or even Sweden, where we have a far-right party, or America. It's so polarized, and I think it's important to, in a subtle way at least, take a stand. Maybe some people who see a film walk out of the cinema thinking about what they've just seen."

And what would Akin say if his film went on to win at the Oscars and he found himself standing on an international stage?

"My gosh. I would say basically that love is love and we need to stop fighting about stupid shit and worry about the real problems we're facing. For instance, climate change."

Watch the trailer for And Then We Danced below. The film premieres February 7 in the U.S.

Pictured: Levan Gelbakhiani (Merab), center

Pictured: Levan Gelbakhiani (Merab), center

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes