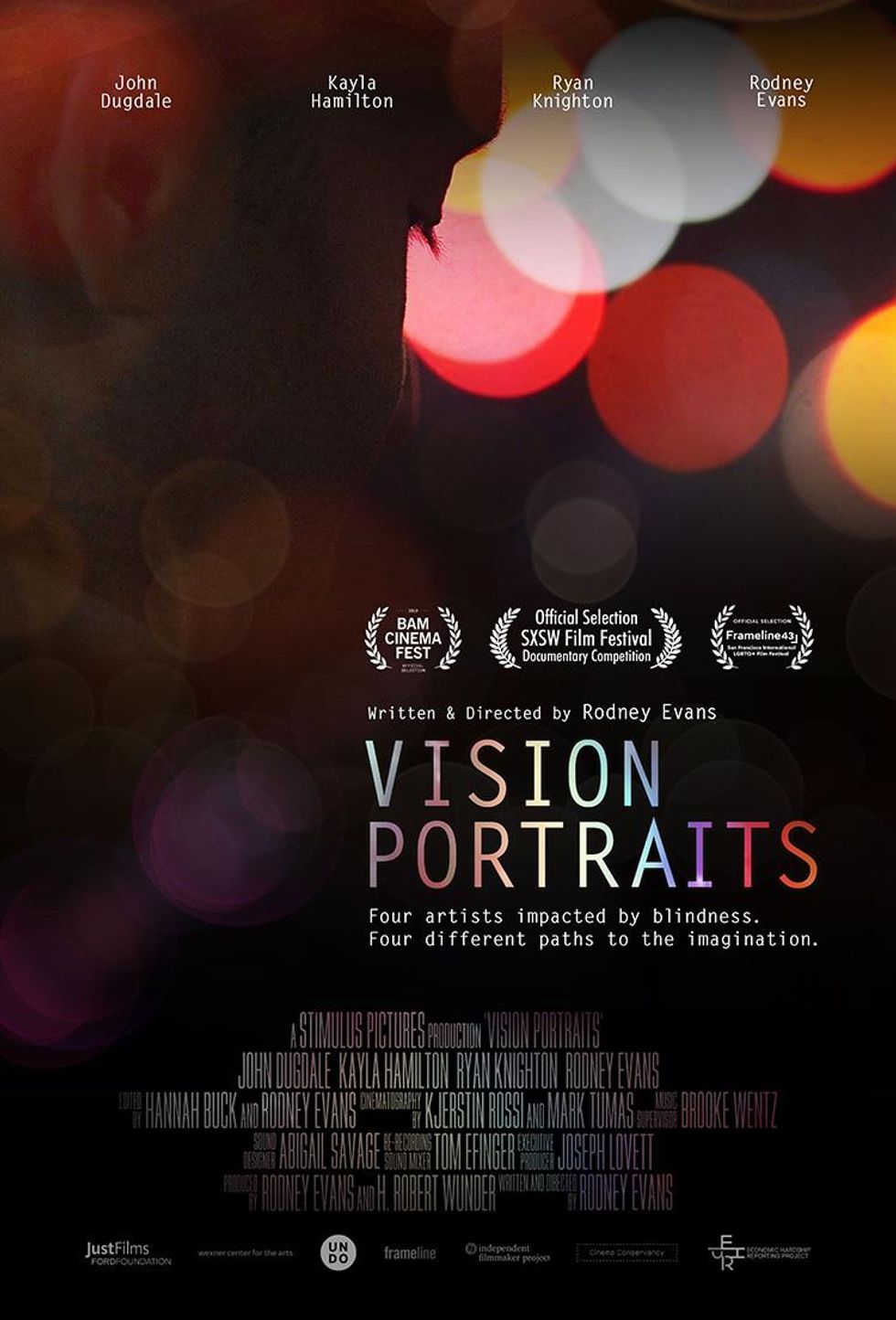

Rodney Evans, best known as the writer-director of the 2004 film Brother to Brother, has a career that's spanned over 20 years. In his new documentary, Vision Portraits, Evans chronicles the lives and creative processes of four visually impaired or blind artists, including Evans himself.

Evans continued to make films even as he began to lose his vision due to a rare genetic eye disorder. "I made 20 years' worth of films as a visually impaired individual. That's a track record that I'm proud of."

Vision Portraits expands popular assumptions about who is allowed to create art, recasting disability as something that can enhance, not diminish an artist's career.

[Click here to listen to the full podcast interview with Rodney Evans.]

Jeffrey Masters: Early in the film, you say you were afraid of people finding out you're visually impaired because it would affect you being hired for more work. What changed? Why decide to come out about this now?

Rodney Evans: It just felt important to the film, honestly. It felt like I was having specific kinds of conversations with these blind and visually impaired artists from an insider's perspective.

It felt like I was having shared experiences with them in relationship to the red-and-white cane. For example, When do you start to feel the need to use it in life? When can you stop "passing" as fully sighted in the world? When are you bumping into too many things? When have you had too many hostile encounters with people?

The intimacy and the trust was coming through in the kinds of interviews I was getting from the subjects in the film.

So you came out as having a disability to serve the film, not for a larger, more personal reason?

Yeah. It made it a better film. And it released me from any fear or shame or burden.

I made 20 years' worth of films as a visually impaired individual. That's a track record that I'm proud of.

On-screen, the percentage of characters with disabilities is extremely low.

Yeah. It's shockingly low. And I do think that looking at it from the perspective of different movements, we're just at the beginning. Just thinking about the LGBTQ representation that existed before the 1990s, before that whole New Queer Cinema explosion that happened, and how hungry everyone was for certain kinds of representations, how hungry I was, frankly, and how that motivated me to want to be a filmmaker.

My professors who would show me Looking for Langston by Isaac Julien and Tongues Untied by Marlon Riggs, and tell me that was all that existed in terms of Black queer experience on film. And so instead of being whiny about it, I just decided to be proactive about it and to create the images that I wanted to see on-screen.

And so it's the same thing with disability. Frankly, it's just bad business. If 25 percent of the people in this country are identifying as having a disability, you might want to have some characters that are reflecting their lives that they can empathize with and identify with. What are you afraid of? is my question.

Can you define what "visually impaired" means in your case?

I describe it as a horse with blinders. I describe it as having tunnel vision, right? I have no peripheral vision and minimal vision. I don't see things below my chin. I don't see things above my head. But I have a very, very clear central vision.

So if I'm looking directly at you, I see everything about you. I fully take you in. But if you come up to me, you're a blur to me. I see parts of your face, but not enough. So I need a certain kind of distance to be able to take in your face.

And so that enables you to still be able to make films.

I think it's what helps me, frankly, get good performances from actors, because actors are so used to people directing them from video village and not paying attention to what's happening on their face and not knowing whether they're in the moment or not where I'm literally right next to you. And I'm looking at you. And I know where you are. And I know what needs to be happening in this scene in order for this narrative to progress in a specific way.

When you first got the diagnosis, was work the first thing you thought about?

No, I don't think it was work. I think it was more safety. I guess there tends to be this sort of doom-and-gloom narrative that gets placed on this kind of diagnosis that I have to say that I didn't experience that much.

For me, it was almost helpful to have some reasoning behind all of these missed visual cues that I was experiencing, the hand that got extended for a handshake that I didn't see where someone would say, "Aren't you going to shake my hand?" And I would be really embarrassed that I didn't see their hand.

As a gay person dating, how do you see your disability being experienced?

It's hard to say, because I don't experience it from their perspective. But I do think that if I were in a bar with a red-and-white cane, I would probably be less likely to be the person that got walked up to, if that makes sense.

You fold up your cane at the bar?

Sometimes, yeah, if I just don't want people to ID me in that way, I don't want people to think about that. If it's well lit enough, if I feel like I'm not going to stumble over a chair: Safety first.

If that bar is really dark, I am going to have a cane out because I'd much rather navigate that space safely and get to the bar safely and not bump into someone who's carrying a beer and get into some crazy brawl over bumping into them. I'd much rather just stay safe. But if it's well lit and I don't need the cane, sure, I'll put it away.

It's so interesting that with your disability, you have the ability to fold your cane up and go stealth if you choose.

I get that. In some ways, it's a good filter. It's like, if you can't handle that, then I'm not going to fuck with you.

Part of the reason for making the film was your search for guidance on how to be a visually impaired artist. Where are you at now with that question?

I feel like I've come to a place of acceptance and of knowing what I am capable of and knowing what I have to contribute and knowing what kinds of stories I'm looking to tell.

I have this saying like, "Every project is a passion project," because I don't understand why one gives over three years of their life to something that's not a passion project. That just doesn't make sense to me.

Put your passion into it. Put your heart into it. If you're not, then do something else.

[Click here to listen to the full podcast interview with Rodney Evans.]

Vision Portraits opened last Friday in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal, and a national rollout will follow.

New episodes of LGBTQ&A come out every Tuesday, only on the Luminary app. Click here to listen.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes