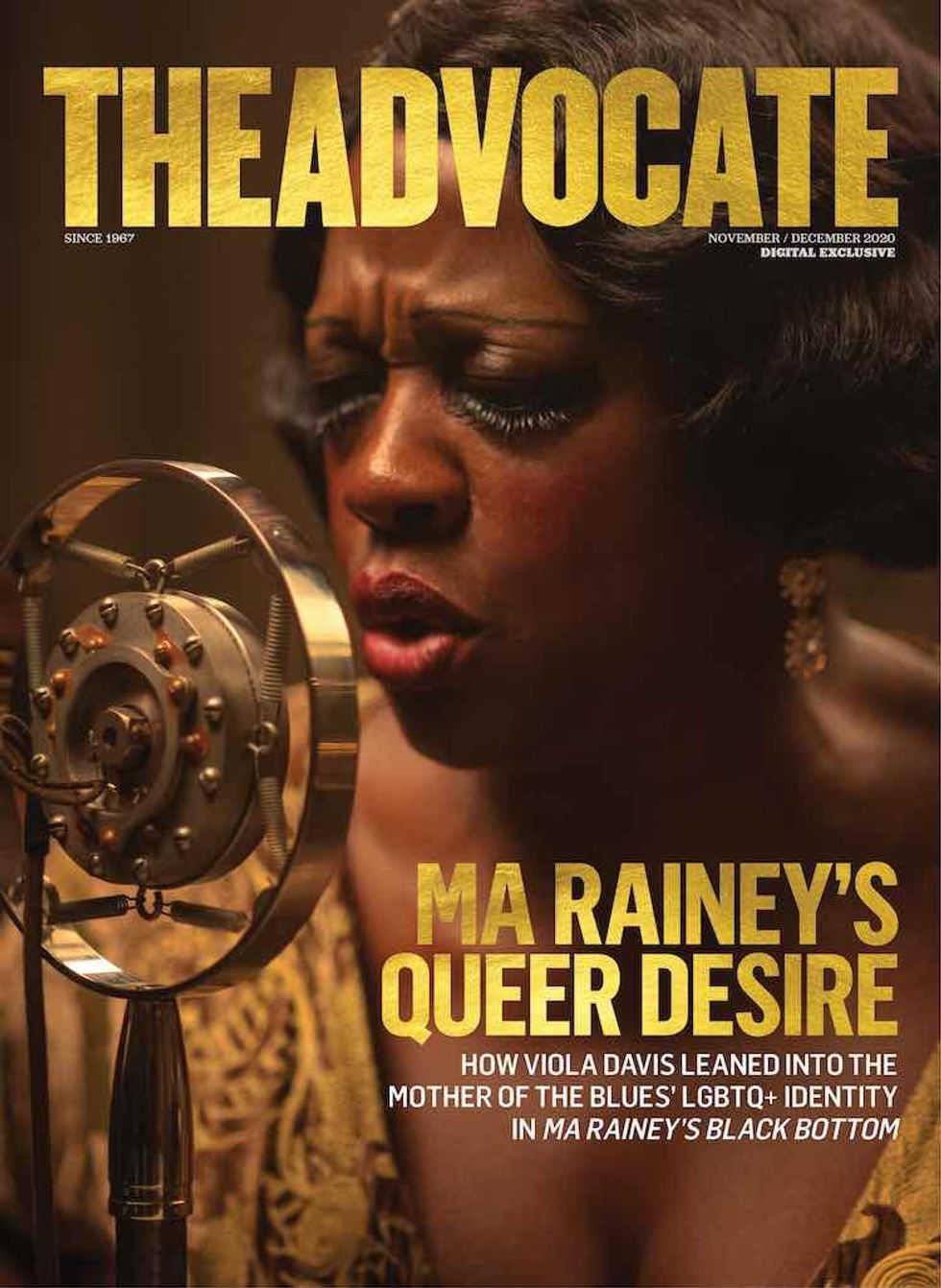

"They say I do it, ain't nobody caught me / Sure got to prove it on me / Went out last night with a crowd of my friends / They must've been women, 'cause I don't like no men," Ma Rainey declares in "Prove It on Me Blues." That 1928 tune isn't performed in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, the new film based on August Wilson's 1982 play that premiered Friday on Netflix. But Viola Davis, who is deeply familiar with Wilson's oeuvre -- she won an Oscar for her role in the 2016 film based on his play Fences -- quotes that song in revealing how she leaned into Rainey's unapologetic queerness. As Rainey, Davis oozes with sexuality, not only in the opening scenes when she's flanked by writhing women onstage, or in scenes where she holds her girlfriend Dussie Mae from behind -- but with every wave of her fan, each note she belts, and every chug of her ice-cold Coca-Cola.

"In researching Ma Rainey, she was unapologetic about her sexuality," Davis tells The Advocate. "This is a woman who went to orgies. She was arrested at an orgy. I felt like Ma always had a woman with her. A lot of the women who dance with her were her women. She had orgies with them. That was her world. I didn't want to sweep it under the rug."

At 19, Davis was first introduced to Rainey when she took in a production of Ma Rainey's Black Bottom at the Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, R.I., with Barbara Meek in the titular role.

"Barbara Meek was the actress, for me. I just felt like she was transformative. She was great. She was all those reasons why I studied acting," Davis says.

"What struck me is from the moment she came on the stage, [Rainey] knew her worth. I did not see a woman who had to scream for it, yell for it, whatever. She just absolutely took the space without out apology. And I loved it," Davis says. "My heart pounded. I thought it was fantastic. That was my introduction to Ma."

The film, from acclaimed Broadway director George C. Wolfe with a screenplay from Ruben Santiago-Hudson (the team behind Lackawanna Blues), unfolds over a single day at a recording studio on a sweltering summer day in Chicago where Rainey and her band are laying down some tracks. It's set during the Great Migration when Black people left the South for the North in droves under the promise of more opportunity. It's also a pivotal time in music with Rainey (the "Mother of the Blues") representing the old guard and Chadwick Boseman, riveting in his final role, as the charismatic horn player Levee, who ushers in a new sound and often without Rainey's permission.

In the fictional story of Wilson's play and the film, Rainey and Levee clash over how her music should be played for audiences in the North who Levee says crave his fresher sound. The other members of her band, Cutler (Colman Domingo), Toledo (Glynn Turman), and Slow Drag (Michael Potts), are true to Rainey's style while humoring Levee, until systemic racism and the events of the day boil over. Always on the periphery are the white appropriators, Rainey's manager, Irvin (Jeremy Shamos), and the head of the studio, Sturdyvant (Johnny Coyne).

Davis, Taylour Paige, and Dusan Brown

The film opens on a prelude, a scene of Rainey performing in a tent in the South -- owning her world. It's followed by a scene in which Rainey plays an established theater where her female dancers, gyrating and pulsating with sexuality, orbit around Rainey belting to the back row. At Rainey's side for much of Ma Rainey's Black Bottom (the title of her signature song that she records at the session) is Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige), a young, beautiful femme who's literally moved by Rainey's music but who also has an eye on Levee.

There's a critical scene early in the story when Rainey first arrives at the studio with Dussie Mae and her nephew Sylvester (Dusan Brown). Rainey holds Dussie Mae from behind, leaning into her neck, whispering, seducing her in the wide-open space of the room. It's the only scene of physicality between Rainey and her young girlfriend. And Davis makes the most of it.

"She's cute. Dussie Mae is cute!" Davis says, before explaining why they worked the scene several times.

"I felt that the thing that was really tricky about this [scene] is, it's sort of public. But it's private. They're in the recording studio. Sylvester is there, all of that," Davis says. "I was like, OK. How do I show this? I don't want to have any inhibitions. I don't want it to look disingenuous."

"It's really interesting when you do all this, Oh, I don't want to do this. I don't want to do that -- because she's queer. She's gay. When in reality, I know these people who are sexual, who are absolutely public about it," Davis says, adding that she arrived at the conclusion that Rainey would have demonstrated her queer desire in that open space.

"She would be. She would enjoy it. Because it's part of her in her world. It's part of my power. It's part of what's owed me. Dussie Mae is mine. And so this is just something I enjoy," Davis says, channeling her thought process as Rainey. "I didn't want to make it look like it was a bad part of her or anything. We worked on it to be completely uninhibited. And so we did that scene so many times."

Of course, it's not Davis's first time playing an LGBTQ+ character. She made history as Annalise Keating, the Black queer leading character of Shonda Rhimes's wildly successful network series How to Get Away With Murder. Not only did she become the first Black woman to win a Primetime Emmy for Oustanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series in the role, Davis knows something about playing characters whose stories have yet to be truly told.

"I just saw this woman [Annalise] who literally got to the point of looking for love and being sort of intoxicated by people, whether they were Black or white, or men or women. And I thought that's fascinating. Interesting," Davis says. "Not only is it vastly interesting, those are people I know in the Black community. They're just not seen. They're not written for. So I'm like, you know what? It's about time it happens."

Wilson wrote Ma Rainey's Black Bottom nearly 40 years ago, and it's set in a time that's now nearly 100 years ago. Still, its themes of holding power and basking in music and joy amid white oppression are as prescient as ever. Davis mentions Rainey's "worth" and "what is owed to her" a few times. Before Rainey has even arrived at the studio, Sturdyvant dubs her as difficult in a pervasive stereotype that Black women continually face. A powerful speech in the film that addresses systemic racism and white appropriation of Black culture has Rainey telling Cutler, "They don't care nothing about me. All they want is my voice."

Davis's Rainey holds on to her worth and to what's hers. And Rainey's overt queer desire is a part of that power.

"There is a culture out there that fears you so much, that fears whatever you represent. And so what they do is instead of dealing with their fear, they stigmatize you. they call you difficult. They call you ugly, that's a big one, for me. They do anything to erase you and your power.

"It's still very prevalent today. It's definitely prevalent in the Black community. It's prevalent in the LGBTQ community. It's prevalent in any community where people are on the periphery. They just want to erase you.

"One of the things I like about Ma is she knows that. And she doesn't accept it. And she doesn't fear it," Davis says. "I love that. Because I know a lot of women like that, especially Black women in my life."

Watch Davis's full interview with The Advocate above.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes