Neurologist Oliver Sacks devoted his life to treating people with cognitive disorders, often severe ones, and writing eloquently about them in books such as Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. But few knew of the difficulties the kindly, erudite doctor and scientist faced in his own life.

Those struggles included Homophobia, which was easy for him to internalize given that his mother called him an "abomination" when she found out he was gay. A seriously ill sibling. Amphetamine addiction. Lack of respect from fellow scientists. And a fear that he'd never know romantic love, only to find it in the last few years of his life.

All this and more are revealed in a new documentary film from director Ric Burns, Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, opening in virtual theaters today.

"Nothing in his writing would tell you that being Oliver was a very tough row to hoe," Burns tells The Advocate. His struggles, Burns says, became the foundation on which Sacks built a remarkable career, treating people who had more daunting problems.

Burns was familiar with Sacks's writings but had never met him when he received a call from in January 2015 from Kate Edgar, his longtime editor and collaborator. Sacks had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer, which would take his life in August of that year, and had also just finished writing a memoir. She felt his life had to be documented on film, so within a few weeks Burns and his crew arrived at Sacks's Greenwich Village apartment to begin shooting.

Burns found Sacks to be "very reserved and incredibly open -- he was always both one thing and another," the filmmaker says. In the film Sacks comes across as gentlemanly, even courtly, but he can unexpectedly drop a string of profanities or break out with a ribald and hilarious story about an unusual use for orange Jell-O.

Sacks was 81 when Burns met him. The scientist was born in 1933 to an accomplished Orthodox Jewish family in London. Both of his parents were doctors, his mother being one of the few women surgeons at the time. Oliver, the brilliant and doted-upon youngest son, and two of his three brothers would follow their parents into medicine. But one brother, Michael, developed schizophrenia. Oliver worried it would happen to him, while their parents felt shame and stigma.

Another source of shame, for Oliver, was being gay. At one point in Oliver's youth, his father said he noticed Oliver didn't have girlfriends; was he by any chance attracted to boys? Oliver said yes, and his father passed that information on to his mother, who called him an abomination and then didn't speak to him for several days. When she resumed speaking to him, she never mentioned the subject again, and later she advised him on his writings, but the damage was done.

Burns, a straight man, says he didn't know Sacks was gay until he received the phone call from Edgar. "So much of who Oliver was, was hiding in plain sight," the filmmaker says, adding, "When your mother says you're an abomination, that's not going to encourage your openness about your sexuality."

Being gay in England in the 1950s was dangerous; engaging in gay sex could get a person arrested or even, in the case of the great computer scientist Alan Turing, chemically castrated. There was still plenty of homophobia elsewhere, though, as Sacks found when he came to the U.S. in 1960, first to San Francisco, then to Los Angeles and New York City. In the film, he describes a painful encounter with a straight roommate when he couldn't hide his physical response to the man.

But Sacks threw himself into bodybuilding, motorcycle riding, and amphetamine abuse -- and his work. He got off amphetamines in 1967, but the previous year he had already entered a notable phase in his career, working with patients at Beth Abraham Hospital in New York who'd been in a trancelike state since having had sleeping sickness 40 years earlier. He treated them with an experimental drug, L-dopa, which enabled them to awaken, to move, to communicate.

However, the drug was not a panacea -- it had extreme side effects in many patients, and some didn't care for the strange world into which they'd awakened. Still, Sacks documented the experience in the 1973 book Awakenings, which was made into a popular 1990 film starring Robin Williams as a character based on Sacks and Robert De Niro as one of his patients.

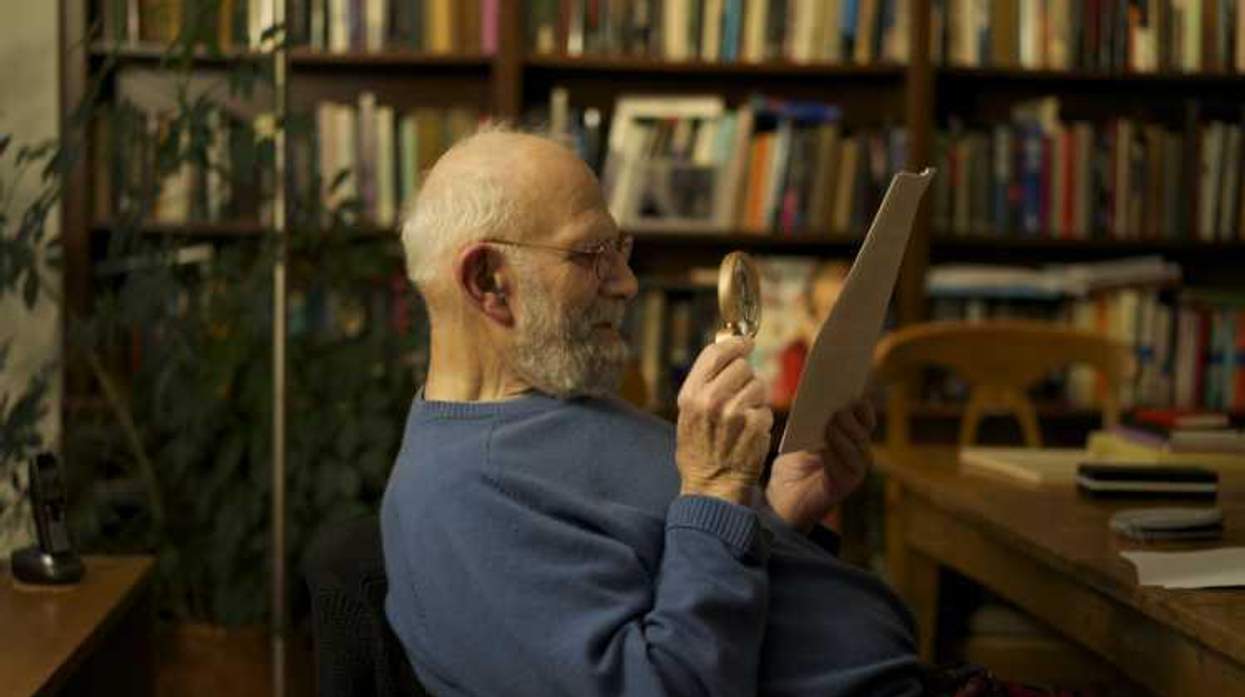

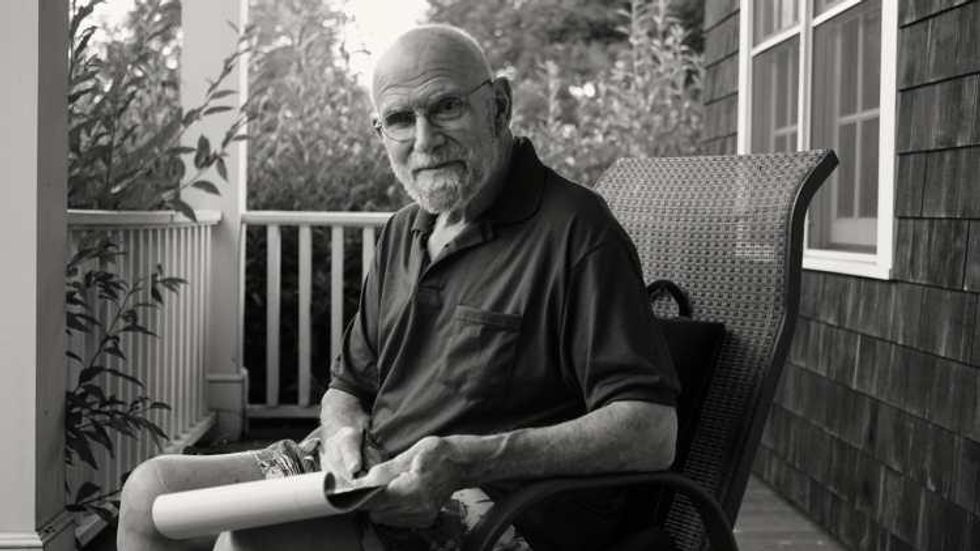

Oliver Sacks, photographed by Bill Hayes

Some other doctors and scientists were skeptical about the book, thinking Sacks had embellished the story, but he continued treating patients for a variety of neurological conditions and writing about them. There were critics who accused him of exploiting his patients, but colleagues, friends, and patients interviewed in the film reject that characterization, saying he didn't exploit them but helped the public understand them.

Dealing with people who had such conditions as Tourette's syndrome, autism, musical hallucination, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, and more, Sacks helped them see that they were not "less than" others but in some ways "more than," according to the film. He comes across as empathetic and compassionate, a doctor for whom the primary diagnostic question was "How are you?"

And Sacks didn't slough off his own difficulties, but "he doesn't collapse, he doesn't fold inward," Burns says, adding, "He might be tormented, but he was going to be himself no matter what it took."

He finally started getting respect from fellow scientists around the time the film of Awakenings came out. And he found love, after a 35-year period of celibacy, when in 2008 he met Bill Hayes, a photographer and writer who admired his work. They stayed together until Sacks's death.

Burns predicts viewers will find hope and inspiration in Sacks's story. Sacks was "a guy who had every reason to fold his tent and creep away," but he didn't, and he "did arguably more than anyone else to help people understand being a conscious human being," the filmmaker notes.

Filmmaker Ric Burns

Oliver Sacks: His Own Life was shown in a few film festivals before COVID-19 shut down theaters, but Burns and his team found an alternative path to getting it out to the public, with virtual screenings beginning today (find a list of theaters and buy tickets here). The film will then go to streaming services and will be televised on PBS's American Masters in April. "We just hope as many people as possible see it," Burns says.

Burns, whose other credits include New York: A Documentary Film, The Donner Party, The Way West, Andy Warhol, and The Chinese Exclusion Act, has stayed busy during lockdown. He's been preparing a timely film titled Driving While Black, an exploration of the Jim Crow era based on research by African-American historian Gretchen Sorin; it will air on PBS October 13. And he's working on a big project for next year on the medieval Italian poet Dante Aligheri.

He got his start in documentary filmmaking by working with his brother, Ken Burns, on Ken's landmark series The Civil War. "What a blessing to have learned how to make a film standing next to Ken," Ric Burns says. The two "fight like cats and dogs because we're brothers," he says, but also "finish each other's sentences and know what each other are thinking."

Both brothers have chronicled many remarkable lives, and the film on Sacks adds to that count. After getting to know Sacks, Ric Burns says, "you feel better about the world. ... I hope that people find relief in Oliver's work."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes