The temperature is mild on a recent afternoon, but the wind still whips off the water of the Hudson River as one walks west on 33rd Street from Manhattan's Penn Station through a massive construction site that is the city's much-anticipated Hudson Yards mega-development. Finally, inside a towering concrete bunker that houses the Associated Press, one finds GMHC, the country's first AIDS agency and a pioneer in HIV services and prevention. The organization has made this its home since 2011 after moving here from Chelsea, its longtime base.

The ground-floor entrance, separate from the building's main entrance, feels cold and cinderblocky, but upon arriving on the sixth floor, one finds a convivial, multiracial crowd of about 100 HIV- positive clients, many over the age of 50, some with obvious disabilities from decades of living with AIDS. They're gathered in a bright, cheery dining room eating a delicious lunch of homemade split pea soup, chicken with mushroom gravy, veggie quiche, mashed potatoes, salad, and oranges. At the moment all but one of the diners are men, even though GMHC, which stopped using its full name--Gay Men's Health Crisis--a few years ago so as not to suggest it served only gay men, claims that 25.4% of its clients are women. There's plenty of chatting, flirting, and affectionate hugging; many clients give a thumbs-up to the adored longtime chef, Wilson Rodriguez.

"We'll have 500 people here for Thanksgiving dinner," says Krishna Stone, GMHC's longtime communications staffer. "We had a guy one Thanksgiving who cried because his own family wouldn't accept him that day, but he had a home here."

HIV-positive New Yorkers, many of them gay and bi men, have had a home at GMHC since 1982, when playwright and activist Larry Kramer and a handful of other professional white gay men founded the agency amid shocking public indifference to a disease that was suddenly striking down homosexuals left and right. But these days, there's more home than there are inhabitants; a post-lunch tour of GMHC's two sprawling floors revealed large expanses of space that are eerily, depressingly, expensively deserted. When the organization moved in, GMHC intended both to scale up services and sublet extra space to smaller nonprofits to help with the rent, says Stone. But as of today, three years after the move, that hasn't happened.

The relocation itself was fractious. Almost three years ago, in a move that Kramer himself noisily protested, GMHC exited the run-down, multilevel townhouse-style building that had been its headquarters since 1997, fleeing the prospect of a huge rent hike on a burdensome lease by a notoriously nasty landlord. It moved here, to this far-flung street, a minor slog from Penn Station in an end-of- the-earth part of town with no neighborhood identity, let alone a gay one. Plans to grow into the giant space or to sublet unused parts to like-minded nonprofits have not materialized. The agency is spending $4.6 million a year, about one-fifth its total revenue in 2012, on rent for a mostly vacant space.

Left: Former CEO Dr. Marjorie Hill

Left: Former CEO Dr. Marjorie Hill

"They have a huge problem with their real estate right now," said a longtime GMHC staffer who left in recent years. Most of the people who spoke for this story are or were until recently GMHC staffers, board members, and clients, and most spoke anonymously in order to be frank without incurring grudges. (Full disclosure: this writer is a former Housing Works staffer and a former GMHC volunteer and consultant.)

GMHC's real estate problem has become the symbolic centerpiece of a once mighty agenda-setting agency that has found itself badly adrift in recent years even as it ably continues to deliver certain core services, such as a daily hot lunch and mental health and legal counseling, and as its celebrity-studded annual AIDS Walk still brings in millions of dollars--a large chunk of which goes to the private company that organizes the event.

"I love them and the work they do, but there's a lot that's problematic there, especially with the leadership," says one former staffer. "If they truly want a new direction, they need new leadership."

Some of this decline has been happening slowly for years. Since the advent of effective HIV therapies 17 years ago transformed AIDS from a boiling crisis to a muted but persistent one, it's well-known that GMHC has not been able to attract the kind of funding from New York's rich, liberal private sector that it did back in the days when, with its info hotline, one-on-one Buddy Program, and bold, same-sex-kissing subway ads, it pioneered a national model for com- passionate AIDS services and candid HIV prevention.

"All that money's moved on to marriage equality," says a former board member. "The wealthy gay white men this organization served early on in the crisis have left it behind as the epidemic in New York has hit more women and gay men of color."

Image credit: Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images

Above: GMHC's annual AIDS Walk

Above: GMHC's annual AIDS WalkBut in recent years, amid a background of skyrocket- ing rents and federal funding cuts under sequestration, the agency has suffered more woes. The largest by far involves the new space--a deal that Dr. Marjorie Hill, a towering, poised, lesbian African-American former city public health official who helmed GMHC from 2006-2013, pushed through despite opposition from a core group of clients who didn't want to leave its longtime Chelsea home. Those clients called on Kramer to lead a protest rally outside the old build- ing. Over lunch at GMHC, Hill mollified Kramer, telling him the move was for the best. Kramer backed off, only to decry the move again when he learned Hill was planning on jettisoning GMHC's hot lunch program (which she ultimately didn't do).

"There was no transparency about the move, no communication," says Victor Benadava, 51, HIV-positive since 2000, who was chair of GMHC's client advisory board when the move was on the table. "Dr. Hill was always smiling, but everything was done in secret." GMHC claims that most clients supported the move, but many say clients complained vocally about early reports that the new building would require GMHC clients to enter by a separate portal, suggesting they were pariahs, and that it wouldn't allow a full kitchen or on-site medical facilities such as HIV testing and counseling, long a key component of GMHC.

"Marjorie was obsessed with the idea of instead having a stylish cafe space that served soups and panini--a space she'd want to have lunch in herself," says a former staffer. "Half the clients didn't even know what panini was. It took her a long time to really understand that clients wanted that hot lunch. It was the only meal of the day for some of them."

HIV testing did not survive the move to the new space; GMHC had to rent a facility on nearby West 29th Street. The lounge in the new space was outfitted with furniture donated from the trendy Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams, and the organization touted the fact that the space, formerly TV studios, came equipped with dozens of soundproof rooms, perfect for confidential counseling. But there was still the matter of the square footage, which felt extravagant for an agency that says it serves over 9,000 people a year but which insiders have said that, if you count clients who actually show up regularly, is more like 1,000.

"We did the homework telling them they could do with less space, but they chose more, with the aspiration to keep growing," says David Valdez, a Goldman Sachs exec who joined GMHC's board to broker, pro bono, the real estate deal. He's since left the board but insists the deal was a good one, freeing GMHC from a villainous landlord at a bargain rate given its proximity to Penn Station, a citywide transit hub. A new subway extension which is scheduled to open in summer 2014 will extend the 7 line from its current end at Times Square into the Far West Side, just a couple of blocks from GMHC. According to Valdez GMHC's current rent is essentially locked in until 2018 at which point it will go up, but just how much nobody knows yet. He feels GMHC stands a good chance of being able to negotiate yielding half of the space, vastly reducing the rent. "Now they have an opportunity to fix it, and they have an amazing, valuable asset they can trade back to the market or to their landlord."

Left: Founder Larry Kramer

Left: Founder Larry KramerLate in 2013 board chair Mickey Rolfe said in a statement, "The board of directors believes that we can find a space that better suits the needs of the ever-progressing GMHC and its client services than where we're currently housed." DNAinfo reported that GMHC was working with real estate firm Studley to identify a cheaper space.

Hill did not survive the real estate misstep. In September 2013 she stepped down from her nearly $250,000 annual post as GMHC leader, while on a paid three-month sabbatical that angered many because other staffers were taking salary cuts amid budget constraints. (Meanwhile, demoralized by the fiscal squeeze and leader- ship void, longtime staffers were leaving in droves.) GMHC insists that Hill's exit was a mutual decision, although insiders told local press it was an ouster; Hill did not return requests for comment.

Sources have mixed feelings about her departure. Many say that, with her coiffed hair and long, manicured nails, she was a stylish ambassador for GMHC with public and private funders. "The room always gravitated toward her," says Janet Weinberg, GMHC's interim CEO, who was number 2 under Hill. (Many say that Weinberg "walked in lockstep" with her boss.) "She was a very calm presence, unable to be rattled." But many others say that Hill's queenly poise made her a chilly leader for an agency whose history was rooted in the intimate stuff of direct caregiving.

"People would always say she had a regal bearing," says a former staffer. "I don't know if I'd want people describing me that way if I were the CEO of a service agency." Says Marcelo Maia, a longtime GMHC client who chaired the organization's Consumer Advisory Board under Hill, "She was very condescending to us, the clients, talking to us like we were kids, playing with her nails and looking at us as if we didn't know what we were talking about."

Then again, GMHC has long had a reputation for keeping its clients as clients--a stark difference from the city's other major AIDS agency, Housing Works, which runs a large job training program that places clients in its various revenue-generating operations, such as its popular thrift stores, covers part of the cost of night school so staff can attain advanced degrees, and has clients on its board. Whereas Housing Works' cofounder and longtime leader, Charles King, is HIV-positive, GMHC has not had an openly HIV-positive CEO since the 1980s.

Image credit: Stephen Chernin/Getty Images

Image credit: Massimo Consoli, 1989

Above: Kitchen staff prepares the popular daily hot lunch

Above: Kitchen staff prepares the popular daily hot lunchWith Hill gone, who should move GMHC forward in these troubled times? Nobody I spoke to for this story recommended Weinberg. "She's a lovely, nice woman without the skills, ability, and vision to move GMHC where it needs to go," says a former staffer, echoing others. For her part, Weinberg says she wants to stay on at GMHC, as number 1 or otherwise, to get enhanced mental health and substance abuse counseling services fully licensed and up and running. "I'd love to see that through," she says, insisting that such counseling can help GMHC play an important role in preventing HIV among at-risk New Yorkers.

Should the new CEO be HIV-positive and/or a gay black man-- which, along with

transgender women, is the demographic currently most affected by HIV in the U.S.? Should the CEO be a New Yorker or, like some of GMHC's former CEOs, an out-of-towner? Should they have a strong background in fundraising, management, activism--or all of the above? They're all difficult questions. "It has to be someone with a background in HIV but also grassroots advocacy," says a recent former staffer. "Someone who can get ahead of the trends and be proactive, not reactive. The big issues going for- ward are aging with HIV, mental health. They have to turn outward again, reaching young people of color, especially men. And they have to reengage the gay white community and its money."

In December, Stone said that GMHC was looking for a firm to launch the hunt for their new CEO.

In addition, some say, the agency needs a stronger board. "They haven't had really rich, bossy people on it in recent years," says someone close to the current board. "You need people willing to throw a fit when things aren't going right."

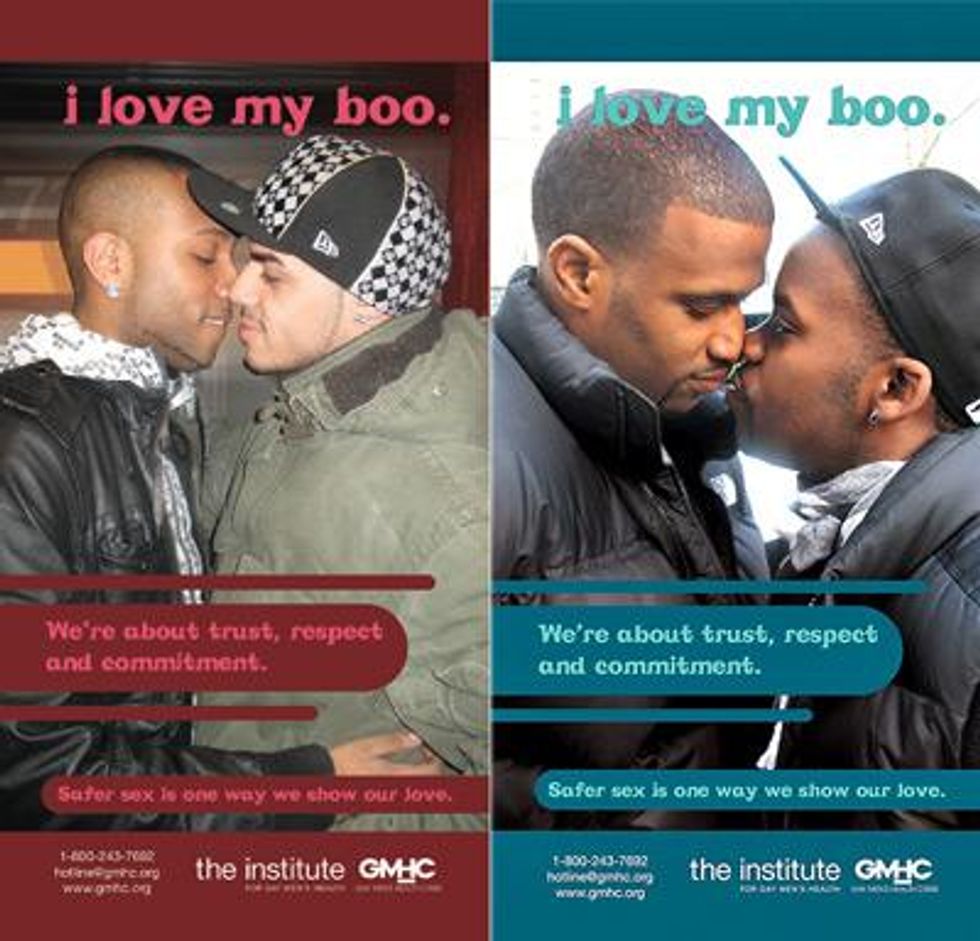

Finally, even if GMHC corrects it finances (the agency posted a six-figure loss in 2012) and its leadership, it will still have to decide what kind of agency it wants to be: one that focuses on direct services, such as meals and counseling, which continues to be a strong suit, or one that tries to regain its 1980s and early-mid-'90s status as a message and advocacy leader on HIV/AIDS in New York. In recent years, GMHC's prevention messaging has been vague, at best. Stone proudly shows off the HIV-prevention palm cards that GMHC has distributed in gay venues in recent years, but the agency has not had a massive subway campaign of the kind that once made waves since 2010's "I Love My Boo" series.

Those posters featured beautiful photos of young gay male couples of color, but did not spell out a blunt message using the word "HIV"--such as the fact that city HIV infection rates among young black men were on the rise while on the decline in the overall population; or even something concrete, such as alerting viewers about post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), an infection prevention tool by which HIV-negative people start a month's course of HIV meds immediately after possible HIV exposure.

Those posters featured beautiful photos of young gay male couples of color, but did not spell out a blunt message using the word "HIV"--such as the fact that city HIV infection rates among young black men were on the rise while on the decline in the overall population; or even something concrete, such as alerting viewers about post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), an infection prevention tool by which HIV-negative people start a month's course of HIV meds immediately after possible HIV exposure.

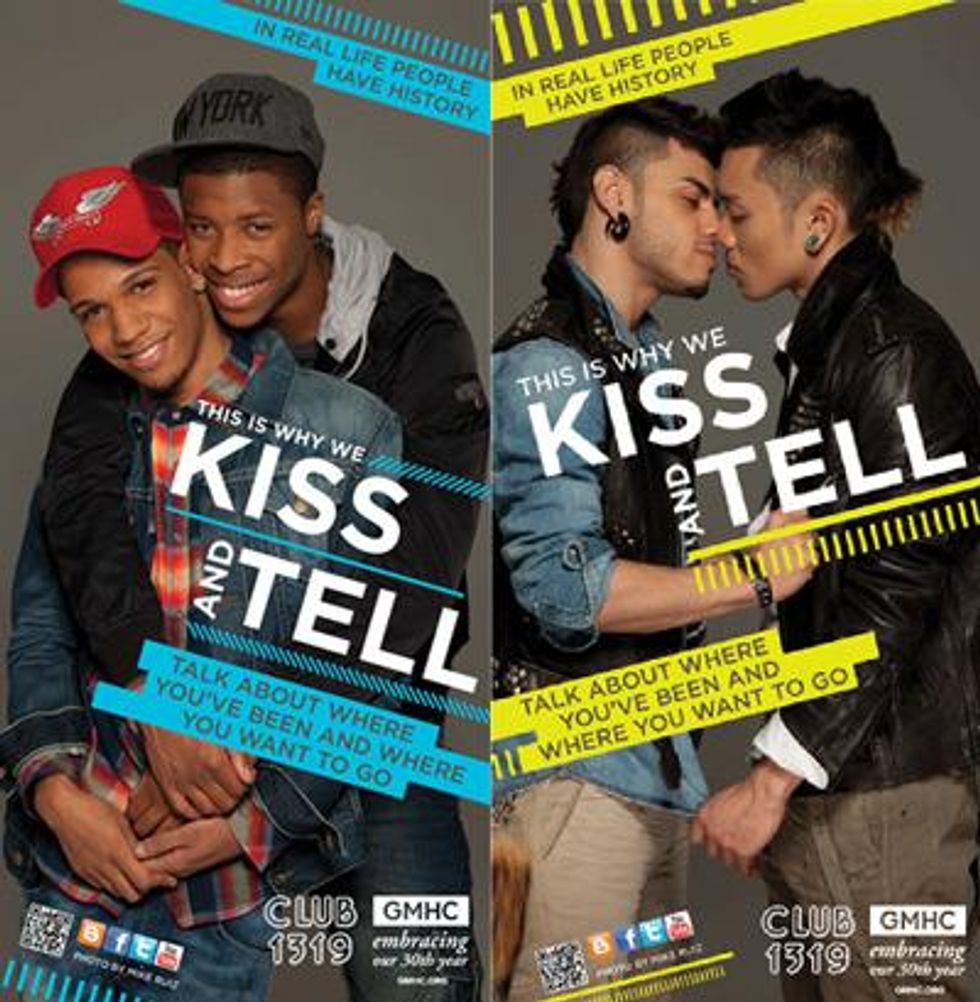

"Aren't these beautiful?" says Stone, showing off an array of cards featuring more cute young gay male couples of color, shot by gay celeb photographer Mike Ruiz. "Kiss + Tell," read the cards. "In real life, people have history." "Talk about where you've been and where you want to go." Nowhere do the cards say anything clear and concrete about HIV or how to avoid it.

Stone says in-house focus groups dictated the cards' content. Weinberg says the unrestricted private money needed to do bold public campaigns has dried up, from up to 80% of the agency's funds once upon a time to less than 50% today.

The agency has also lost ground in the past decade in terms of how strongly it has the ear of government officials in New York City, Albany, and Washington, D.C. It's been surpassed by agencies like Housing Works, Harlem United, and the research-oriented agencies Treatment Action Group and AIDS Community Research Initiative of America, as well as a newly resurgent ACT UP-NY. Those groups are at the forefront of an effort to get New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to take his cue from Massachusetts and San Francisco, which have coordinated tools to dramatically reduce their HIV infection rates, and declare a plan to end the AIDS epidemic in New York State, which has long carried the nation's highest HIV burden.

"GMHC has virtually had to beg to be considered important enough to be part of that discussion," says an activist close to the initiative. "To even get on the email list. They've lost all their influence in the city and state, and even more so among their colleagues at other agencies."

In other words, it's a truly troubled time for an agency that once wrote the book on how to both care for people with AIDS and prevent others from getting it. Can it find new leadership that is truly open to listening to input from below as well as outside? That can balance the demands of financial stewardship in admittedly horrible fiscal times with the daily nitty-gritty of operating services, all while lending a genuinely honest ear and human touch to staff, clients, and the community? That can rebuild relationships with GMHC's forgotten moneyed gay white male past while serving the young gay and transgender people of color most at risk in the city?

It's a tall order. But it was an easy one to hope for that afternoon at lunch, watching GMHC do so well what it has done for 30 years-- even more so now for clients who are aging and seem in need more than ever of the supportive second home that GMHC provides.

"I wish they'd look honestly at where they are now and how far they've fallen," says Jim Eigo, a longtime AIDS activist who, like Kramer, was a GMHCer before he went on to be part of the more political ACT UP. "Having said that, I don't understand the party line that says, 'GMHC is inefficient, so let it sink.' I've been there recently. I can think of at least six ACT UP survivors who get vital services there, including daily lunch. They have to consolidate their resources around those core services."

"I wish they'd look honestly at where they are now and how far they've fallen," says Jim Eigo, a longtime AIDS activist who, like Kramer, was a GMHCer before he went on to be part of the more political ACT UP. "Having said that, I don't understand the party line that says, 'GMHC is inefficient, so let it sink.' I've been there recently. I can think of at least six ACT UP survivors who get vital services there, including daily lunch. They have to consolidate their resources around those core services."

Eigo pauses. "Let's not forget," he says. "They saved this city's gay community. That's a glorious history, and we should help them figure out how to continue it."

Image credit: Courtesy of GMHC

Left: Former CEO Dr. Marjorie Hill

Left: Former CEO Dr. Marjorie Hill

Left: Founder Larry Kramer

Left: Founder Larry Kramer

Those posters featured beautiful photos of young gay male couples of color, but did not spell out a blunt message using the word "HIV"--such as the fact that city HIV infection rates among young black men were on the rise while on the decline in the overall population; or even something concrete, such as alerting viewers about post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), an infection prevention tool by which HIV-negative people start a month's course of HIV meds immediately after possible HIV exposure.

Those posters featured beautiful photos of young gay male couples of color, but did not spell out a blunt message using the word "HIV"--such as the fact that city HIV infection rates among young black men were on the rise while on the decline in the overall population; or even something concrete, such as alerting viewers about post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), an infection prevention tool by which HIV-negative people start a month's course of HIV meds immediately after possible HIV exposure. "I wish they'd look honestly at where they are now and how far they've fallen," says Jim Eigo, a longtime AIDS activist who, like Kramer, was a GMHCer before he went on to be part of the more political ACT UP. "Having said that, I don't understand the party line that says, 'GMHC is inefficient, so let it sink.' I've been there recently. I can think of at least six ACT UP survivors who get vital services there, including daily lunch. They have to consolidate their resources around those core services."

"I wish they'd look honestly at where they are now and how far they've fallen," says Jim Eigo, a longtime AIDS activist who, like Kramer, was a GMHCer before he went on to be part of the more political ACT UP. "Having said that, I don't understand the party line that says, 'GMHC is inefficient, so let it sink.' I've been there recently. I can think of at least six ACT UP survivors who get vital services there, including daily lunch. They have to consolidate their resources around those core services."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered