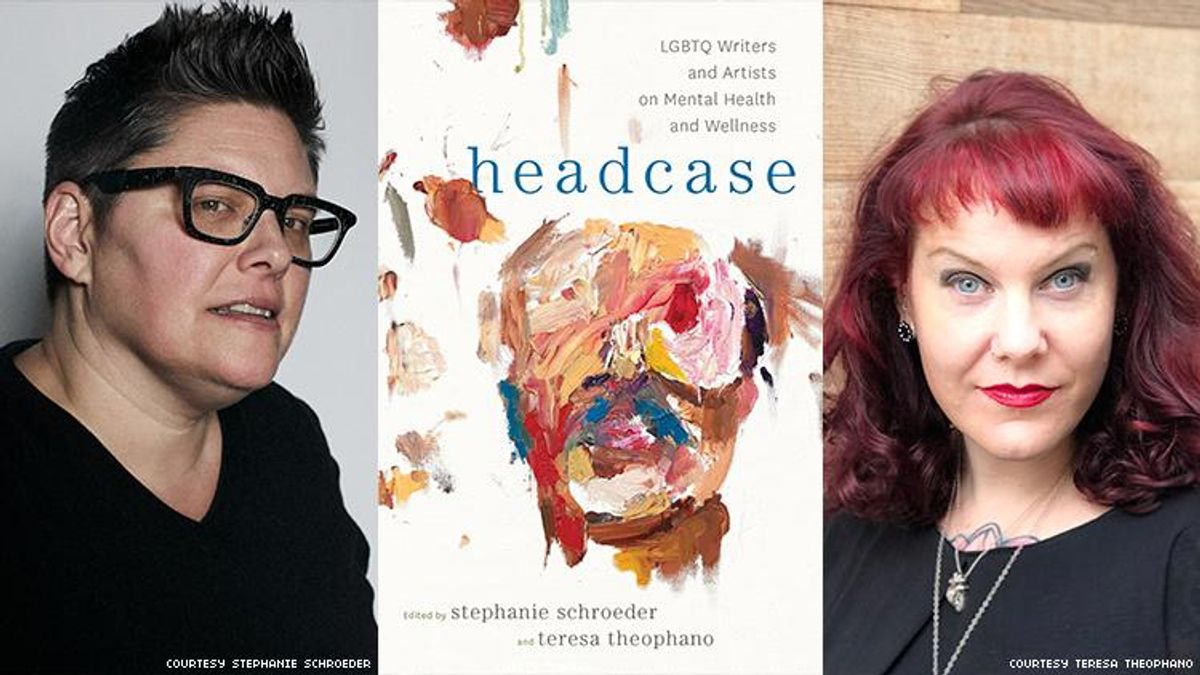

A friend of mine -- let's call her Pam -- has chronic depression. She's lost her insurance five times in the last 18 months, in large part because her insurance premiums are too expensive for her monthly budget. So she's turned to other queers online to find -- and crowdfunding to afford -- the medication that helps her manage her work and family commitments without teetering on the brink of suicidal ideation every day. My friend is just one of the many LGBTQ folks navigating a flawed health care system and their own economic insecurity while dealing with mental health issues. In Headcase: LGBTQ Writers & Artists on Mental Health and Wellness, editors Stephanie Schroeder and Teresa Theophano have assembled a groundbreaking collection of works by folks like Pam who are at the intersection of mental wellness, mental illness, and LGBTQ identity.

The anthology documents the difficulty of navigating a flawed health care system that limits affordable access to genuinely affirming, effective services, which are even more sparse depending on a patient's race, gender identity, age, and socio-economic status. There was no shortage of contributors, says Theophano, a New York City-based social worker who deals with older LGBTQ adults.

She was "blown away by the quality, honesty, and accessibility of the work we received. It was humbling to experience the willingness of so many strangers to come forward and share their mental health-related stories publicly through a variety of mediums, and it reinforced our belief that a book like this needs to exist," she says

Finding a publisher was significantly more difficult. But her editor Dana Bliss, who published the impressive Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, offered them a contract with Oxford University Press.

"Anthologies generally aren't big moneymakers for publishers," Theophano admits. "Five years after we began putting the book together, it's on the shelves at last."

Coeditor Stephanie Schroeder offers one of the book's most revealing essays, about her search for meds, money issues, and the sometimes not-quite-legal lengths those with disabilities and mental health needs may go to in order to remain healthy. Since Schroeder "spilled my guts" in her 2012 memoir Beautiful Wreck: Sex, Lies & Suicide, she felt no fear with Headcase.

"Everything was already hanging out, so I didn't have anything to lose but a lot to gain by publishing my essay about meds, money, and the U.S. insurance racket," Schroeder says. "I actually pieced that essay together from a number of blog posts I wrote during the time I was experiencing enormous hardship and almost lost access to my lifesaving medication."

For Schroeder, her own attempts at navigating the mental health care system in the U.S. turned the full-time writer into a part-time health advocate. "I never hear from folks until they are in a crisis. There are a few free clinics in NYC. One that caters specifically to LGBTQ folks' mental health needs just launched, which is amazing. I also help match members of the community -- and, really, anyone who contacts me for help -- with other folks who can be of assistance in various ways, like helping to fill out forms or to accompany them to a doctor visit or hospital billing office."

But most of all, Schroeder does what she did for herself. She helps "hook up people who need a specific medication with someone who has that med and no longer needs it," she says. "Perhaps they stopped taking it, changed meds, have it left over from someone who used to live with them, or whatever. I put them together, they figure it out, and everyone gets what they need."

It isn't all rosy, though. The health care system itself is an imbroglio, she says, but even "in 2012, 2013, my friends and I were saying the [Affordable Care Act] was a mess, a sham. Now we are just glad to have any coverage or medical assistance at all. We have become pathetic because the current administration is so damn despicable. We've been willing to take crumbs, and for so long, even before Trump."

Even in relatively accessible New York City, Schroeder says, "the really horrifying part is that I'm seeing more and more desperate folks, people in very complicated situations. I see people who make 'too much' money to get help, not enough money to get help, folks who are asking for money directly, and others who are crowdsourcing to pay their medical bills, etc. Many of these folks are transgender and have little or no support or resources. I do what I can, but what I can do is becoming less helpful as the greedy insurance and pharmaceutical companies conspire with our government to keep necessary treatments out of reach for many, many people."

Still, while neither woman has the answer for our health care woes, Headcase will surely help.

"I hope all the stories in Headcase will empower others to speak, write, create, and publish about what is really going on in this country in terms of barriers to mental health care and discrimination against LGBTQ people in the mental health system that is actually many systems," Schroeder says.

And, Theophano adds, they hope the book helps emphasize "that what LGBTQ people with mental health concerns say about their lives and their care matters. The literature on LGBTQ mental health care cannot be exclusively written by clinicians for clinicians -- it needs to encompass peers' expertise on the care we receive versus the care we need, which are too often at odds with each other. It needs to include peer perspectives on what helps them outside of the medical model as well as within it. The process of creating this volume confirmed what we knew to be true: that queer people, as with peers of any kind, are the experts in our own care."

Headcase will surely launch frank conversations about queer and trans mental health, and, Theophano says, that should "ultimately help improve the quality of services provided to our community, by presenting voices and perspectives that are too infrequently granted a public platform. We hope these conversations will take place in classrooms, within communities, among families, and with mental health care providers."

The anthology, which offers a foreword by renowned Canadian writer, performer, and therapist Kai Cheng Thom (author of the novel Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl's Confabulous Memoir), also tackles the lasting impact of historical views equating queer and trans identity with mental illness and the problem with a gay movement that proposes we're "just like you." Schoeder argues that the "assimilationist turn the mainstream LGB community has taken in previous decades through the present day" has hurt folks who aren't "just like" their straight peers (that is, "middle-class white cisgender folks living in segregated suburbia").

But, Theophano adds, "many queers -- especially young trans people, alongside the younger generation of cisgender and straight allies -- want something different, something that speaks to them, something radical, something that does not compromise their identities or creativity or dreams by asking them to be 'just like.' They see that a different life is possible and they strive to create that. Being 'out' about our mental health concerns is one way in which many queer and trans folks of all ages resist assimilation."