Yesterday, testifying before Congress (BTW, isn't Senator Rand Paul an ass?), Dr. Anthony Fauci said he would not be surprised if the United States reached 100,000 positive cases a day. That is mind-blowing.

Also, at the hearing, Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that our nation needs to be over prepared, not underprepared.

"We've really been hit with this simple virus," he said. "We have a moment in time where I think people are attuned, and I would say now's the time to make the necessary investment in our public health, at the local, territorial, tribal state and federal level, so that this nation finally has the public health system not only that it needs, but that it deserves."

Part of that is the development of a comprehensive and modernized contact tracing system according to Redfield, telling the Senate committee on Tuesday that "substantial investment" needs to take place.

"There are a number of counties that are still doing this pen and pencil," Redfield said. "We need to have a comprehensive integrated public health data system that's not only able to do something that's in real time, but actually can be predictive."

And on the same day, Vice President Joe Biden in a speech about confronting the virus, called for 100,000 people to be hired to form a national contact tracing workforce.

But how do you develop and ramp-up a tracing system that has to follow-up with tens of thousands, if not millions, of people who might have come in contact with 100,000 infected people? Moreover, how do you quickly hire, train and deploy 100,000 people in record time? Seems to be more than a daunting task.

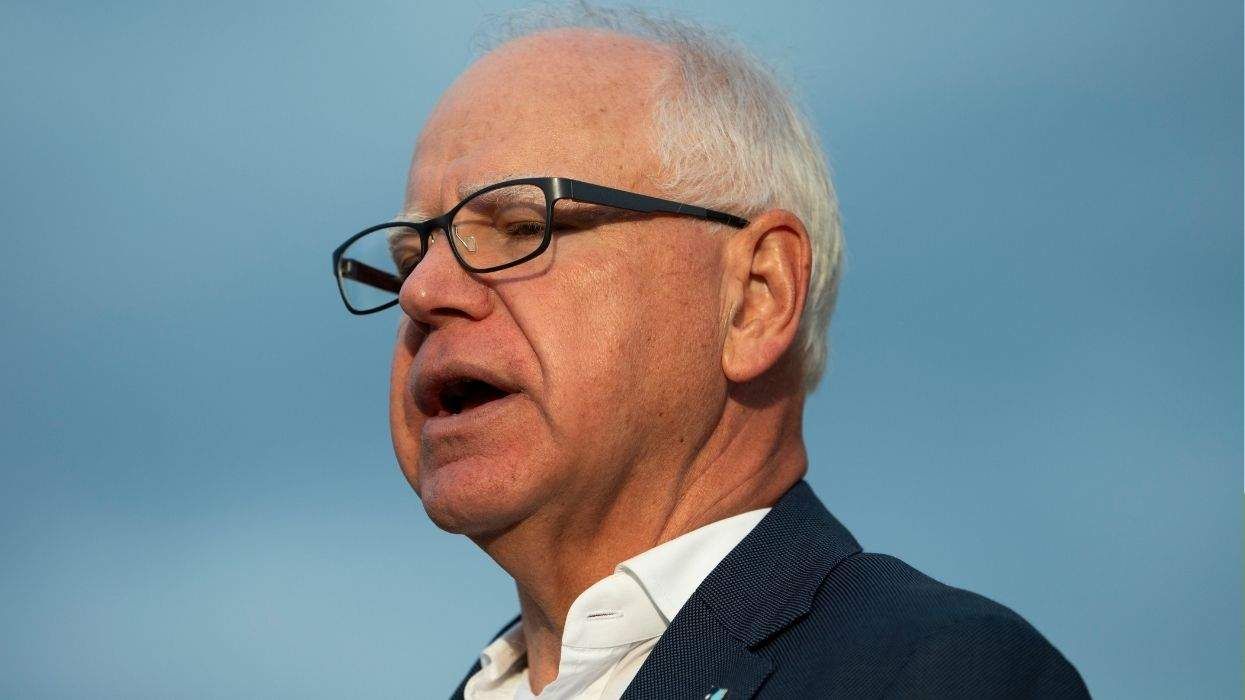

For some clarity, I reached out to one of the world's top infectious disease epidemiologists, Dr. Michael Osterholm, Director of the Center for Infectious Disease and Research Policy at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Osterholm started the very first contact tracing program for HIV in 1985.

"Obviously the goal in 1985 was to identify as many people who were positive, and get people to practice safer sex," Dr. Osterholm explained during a recent phone conversation. "Initially, the challenge was that there wasn't a sufficient benefit to get people to participate, and the program struggled in the early years as a result."

In March of 1987, FDA approved zidovudine (AZT) as the first antiretroviral drug for the treatment of AIDS, and it was then that Osterholm's program began to turn around. "When AZT became available, and we could make the promise that if you were followed up on a positive, we would help you have access to AZT, that changed the entirety of the program," Osterholm said. "There was much more acceptance."

Osterholm also explained that it was critical to also ensure that confidentiality was never breached, and that at that time there were no issues of third party involvement since most of the contact tracing interviews occurred in workplace settings.

"What the early days of the HIV contact tracing taught us was that the incentives have to be there if someone would want to participate, and safeguards in place to ensure that the data was protected, and that there wasn't even a remote chance that the data wouldn't be shared with others or be accessed by others."

Osterholm left the HIV program in 1999 but said that the first 10 years were quite successful since people felt comfortable with the track record of success.

In terms of COVID-19, similar to the early days of HIV, contact tracing programs are off to a rocky start. The New York Times recently wrote about the troubles of New York City's effort. "The city's program has so far been limited by a low response rate, scant use of technology, privacy concerns and a far less sweeping mandate than that in some other countries, where apartment buildings, stores, restaurants and other private businesses are often required to collect visitors' personal information, which makes tracking the spread easier."

According to Dr. Osterholm, those issues are to be expected, particularly in the age of technology. "Some questions we hear now are about third-party vendors' information being shared through apps and being controlled by third parties which puts the vendors in doubt."

"We've raised a lot of issues, and we've also stated a number of ways and things you can do to reduce the risk of COVID-19 disease through transmission," he pointed out. "The testing and tracing combined have some real challenges. You can't just hire more people with more money and deal with it."

"If you look at all 50 states, infections have gone up substantially in so many states in the last few weeks. And, I don't think most states are ready to implement an aggressive contact tracing program so quickly."

Osterholm specified that like the early days of HIV, COVID-19 contact tracing programs aren't offering people enough incentive to share. "If you're infected, or contact traced, you have to stay isolated or quarantined for 14 days, depending on when the exposure was," stated Osterholm. "So, if you're an essential worker, and you don't get paid if you don't go to work, what's your incentive to participate? We haven't worked through those issues yet, and I think that's one of the challenges."

Osterholm added that he'd "throw the kitchen sink at this thing" if it didn't do harm and actually worked. "I come from a world of contact tracing, and I understand the potential power of it. But I also understand the reality of what these programs can do under these conditions."

One example that he alluded to was that during the HIV days, contact tracing was done in person, maybe in an office, or at home, where someone showed an ID that proved who they were. Now most tracing is done by phone.

"The whole issue with that is that it can be difficult for the tracer to verify who they say they are," Osterholm explained. "Any person can create a phone identification by putting something like 'NY State Health Department' on their answering ID. Then the people who are being called see it, and they think that the caller is really from the NYS Health Department. One of the challenges is to work through the scam side of this."

Finally, it's inevitably about who is hired to do the contact tracing. "I can understand why that's a real challenge right now since it's very difficult hiring enough people who are competent. Most applicants and tracers you hire mean well and want to help out. But the question is training. Previously, we spent months training people as contact tracing health investigators, but we don't have time to do that now, so what's the tradeoff for that?"

That's a scary thought. As cars line-up for miles around the country for people to be tested, the system to test is under a tremendous strain. What happens when the testing is done, and you test positive remains an unanswered question, and that's not a comforting thought.

John Casey is a PR professional and an adjunct professor at Wagner College in New York City, and a frequent columnist for The Advocate. Follow John on Twitter @johntcaseyjr.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes