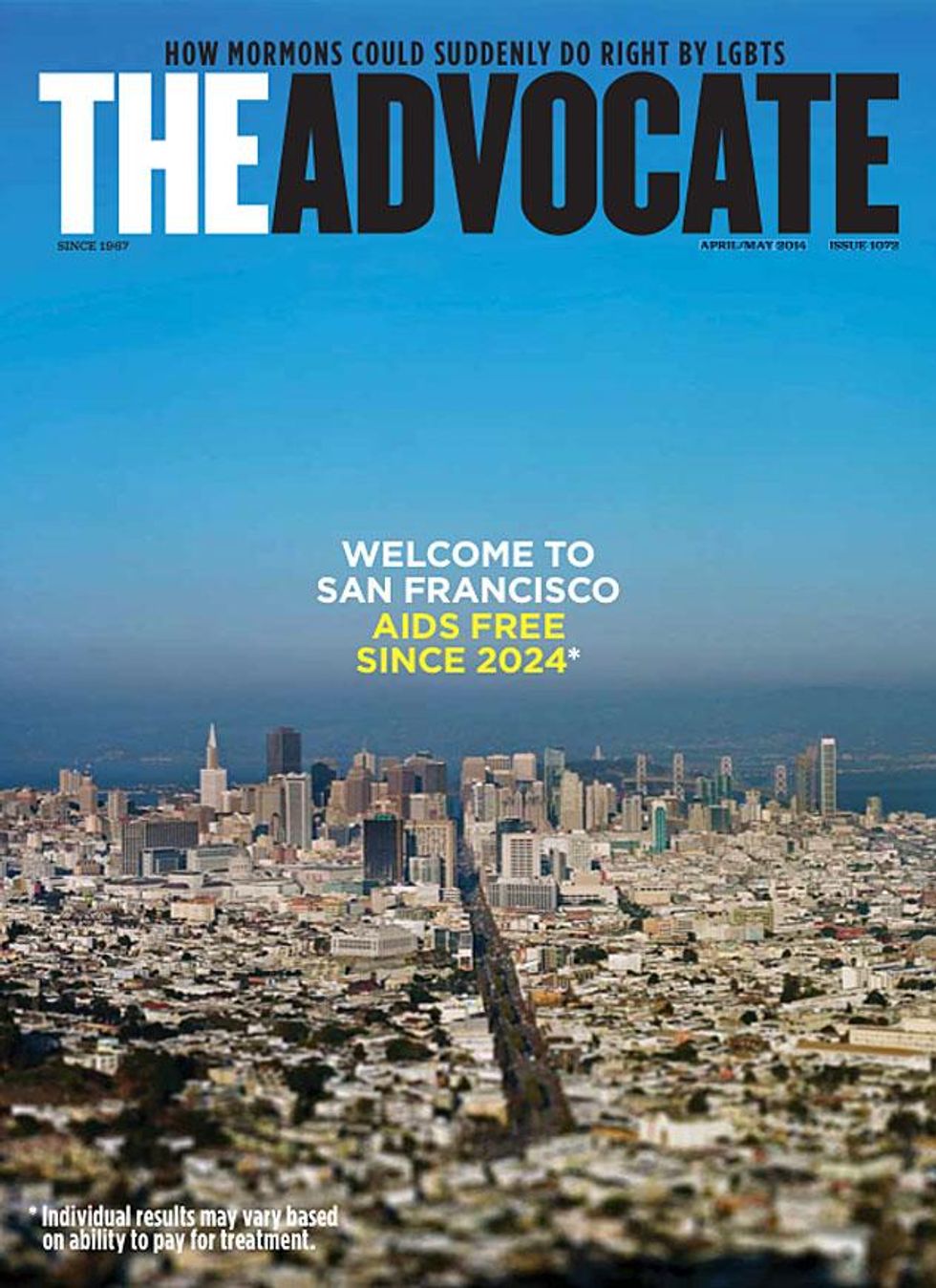

Photographer: James Hosking

This all began with a visit to Ward 86, the nation's oldest HIV/ AIDS clinic. Founded in 1983 at San Francisco General Hospital, Ward 86 was, for many years, a death camp with a dreamy view of palm trees and California sky. In the early '80s, the average life expectancy of patients admitted there was 18 months--it was where people went to die. It was ground zero in America's battle with AIDS, and where so much of the epidemic's early iconography was crystallized: rag-and-bone bodies wasted from pneumonia or encephalitis, catatonia, seizures, bedside vigils. It seemed only appropriate to begin where the epidemic began. Jeff Sheehy, the ward's communications director, is courteous but puzzled.

"There's really nothing much to see," he says. "It's just a clinic." Sheehy's response would have been unimaginable 20 or 25 years ago, but something epochal has happened both in modern science and in the city of San Francisco. While there is still no cure for AIDS, and the rate of new HIV infections has remained relatively stable, the city is redoubling its assault on the disease that has claimed the lives of more than 19,000 of its residents. Inspired by Hillary Clinton's 2011 speech at the National Institutes of Health, in which then-Secretary of State Clinton rallied for "an AIDS-free generation," and emboldened by recent breakthroughs including PrEP and antiretroviral therapy (ART), San Francisco is committed to being the first city to reach zero--zero new HIV transmissions and zero AIDS patients.

There is fierce competition here, especially in the last decade as AIDS researchers have glimpsed a kind of epidemiological horizon. A cure seems all but inevitable. There's the case of Timothy Ray Brown, the "Berlin patient" who was deemed functionally cured of HIV after receiving a 2006 stem cell transplant to treat leukemia. There's the announcement, made at the 2012 International AIDS Conference, that 14 French HIV patients who started an ART regimen months after infection subsequently quit taking the medication with no surge in their viral loads. In April 2013, London's Daily Telegraph reported that a team in Denmark was experimenting with strategies to rout HIV from human DNA for the purpose of nuking it with immunotherapy. These are all milestones, and cities across the country have positioned themselves as beneficiaries--and, in some cases, architects--of the cure. San Francisco is arguably the most determined.

No one knows this better than Dr. Diane Havlir. She began her career at Ward 86 in the 1980s, a time she describes, somewhat demurely, as "extraordinarily formative years." Today she is head of the ward and one of the nation's leading HIV/AIDS researchers. In 2012 she co-chaired the International AIDS Conference in Washington D.C., whose theme, "turning the tide together," and official declaration called unequivocally for ending AIDS. "Now, for the first time ever--we've never really said this before--we think we can begin to end AIDS," Havlir said shortly before the conference.

Her optimism hasn't faded. "It's an exciting time," she says. "We've all been re-energized by a couple of things. First, by the prospect that with earlier treatment and with PrEP we can dramatically reduce the number of new infections, and secondly, by the fact that a cure--that it can even happen--has been proven." The case of the 14 French patients bolstered by early exposure to ART was compelling enough that last year, Havlir and her col- leagues at San Francisco General launched RAPID, a citywide program aimed at getting HIV patients on ART the same day they're diagnosed. In some cases this means that healthcare workers escort patients to Ward 86 in a cab--what I imagine must be the most frightening and tender ride anyone can take through the city's pastel hills. "The data would suggest that people who start treatment immediately after they're infected will reduce the reservoir of HIV in their body, so if a cure were to become available, they'd be in a better position to benefit from it," Havlir says.

And there's the c word again. It's a subsonic hum beneath any conversation about AIDS. The prospect of a cure is both intoxicating and unnerving, namely because failure is not an option. When the subject is raised with Havlir, she hedges. "No one can predict it. The fact that there is investment and commitment means it's going to happen faster than it would have before, when we weren't even thinking about it."

Although there was never a time when AIDS researchers weren't thinking about a cure, Havlir's response indicates the extent to which it will demand deep institutional pockets. UNAIDS and the World Health Organization estimate that curbing new HIV infections--reducing transmissions, not a cure-- would cost $20-$30 billion over the next half-decade. That's a sobering tally, and perhaps one reason why local public officials, policymakers, and researchers eagerly posit San Francisco as the incubator for AIDS innovation. There's a torrential, largely untapped artery of funds awaiting whatever city or institution offers a viable blueprint for significantly slowing transmissions or, better yet, unveiling a cure.

Havlir sees the treatment cascade as one of the city's biggest opportunities to tout benchmarks. Sometimes referred to as the "continuum of care," the treatment cascade is best visualized as an upside-down pyramid identifying stages of HIV treatment where patients are most likely to go AWOL. Of the 82% of people with HIV who are diagnosed, only 66% are linked to care, while 37% are retained in care. Thirty-three percent are prescribed ART, and 25% become virally suppressed. In San Francisco, viral suppression stands at 50%, a number that's double the national average, though it's still underwhelming to Havlir. "We can do much better than that," she says, and goes on to envision a city in which diagnosis, treatment on demand, and outreach services such as housing, substance abuse counseling, and mental health counseling are integrated under one umbrella of care.

If this sounds like a rehash of the vintage "San Francisco model" of AIDS policy, in which a full menu of health and social services are combined under one roof, it is. Thirty years after the epidemic first broke and the model was introduced, it remains the gold standard of HIV/AIDS treatment. Justin Goforth, director of community relations at Whitman-Walker Health in Washington, D.C., praises San Francisco's method of fast-tracking patients to care. It's one his clinic has adopted and rebranded as the "red car- pet entry" program. "Our goal is to link all newly diagnosed individuals or new HIV-positive patients to care within 24-48 hours," Goforth says. "Most of our newly diagnosed patients actually have the first appointment with their provider and other members of their new care team the same day of diagnosis." That protocol mimics San Francisco's RAPID program.

Goforth also mentions the role his clinic takes in crafting HIV campaigns that herald the not-too-distant day when D.C. is AIDS- free. "The newest prevention messages no longer include the word AIDS and speak only of HIV infection," he says. Likewise, Randall H. Russell, CEO of the Seattle-based clinic Lifelong, frames his facility's mission as making Seattle "an environment that will perpetuate an AIDS-free city." Major HIV/AIDS organizations in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York--and indeed all across the country--share the same goal. While finding a cure is a global, collaborative endeavor, wherever it happens is likely to become a tinderbox of enormous economic, political, and cultural capital. So why is San Francisco primed to take the jackpot?

According to Neil Giuliano, CEO of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, the city's notoriously liberal outlook is more congenial to progress. "We still have a ways to go in dealing with shame and stigma," he says, "but I would venture to say we have gone much further than most other urban, and certainly suburban, communities in this country." To prove his point, he hands me a sheaf of posters promoting the foundation's various public forums.

F*CK WITHOUT CONDOMS EVER? LET'S TALK ABOUT IT, reads one.

RAW SEX--ARE THE RULES CHANGING? blares another in a burly, biohazard-colored font. "These are probably not posters that could go up in many communities around the country. It wouldn't work in San Francisco if we tried to do any- thing that was other than very open, very honest."

Giuliano is a relative newcomer to HIV/AIDS public policy. His resume includes four terms as the openly gay Republican mayor of Tempe, Ariz.; four years as president of GLAAD; authoring a motivational memoir-cum-campaign-bio; a midlife conversion to the Democratic Party; and, since 2010, serving as CEO of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. More recently, he's moonlighted as the Great White Hope of Arizona politics. He seems to relish playing coy with the state's media about a potential gubernatorial run. When I meet him at his office four stories above Market Street he's rebounding from a nasty flu, which may explain his affable but somewhat prerecorded demeanor. He is accompanied by James Loduca, the foundation's PR head, who chaperones our conversation.

"This was the first community where HIV was an epidemic in the United States," Giuliano says. "It was in San Francisco, in the Castro neighborhood on Castro Street, where people literally dropped dead while walking down the street. We believe it will be in San Francisco, in the Castro neighborhood on Castro Street, where we will be able to say a new HIV infection is incredibly rare and we're caring for people who have HIV. That's it for us. That's what we're all about."

In practice this means exceeding the goal established by the foundation's board in 2010 to cut new HIV infections by 50% over five years. This target doubles that of President Obama's National HIV/AIDS Strategy, also instituted in 2010, which calls for reducing new infections by 25%. San Francisco halved its number of new infections between 2004 and 2011, and now reports a little more than 300 new cases per year. The city hopes to trim that number by a further 25% this year. It's an ambition many veteran HIV researchers dismiss. Dr. Matthew Golden, director of Seattle's HIV/STD Control Program, deems such a downsizing in new infections as extraordinary. "Could San Francisco go down another 25% in the next five years? Maybe. In the next one year? No way," he tells me.

Giuliano sympathizes with the skeptics. "We have an obligation to be aspirational," he says. "Do I know that we're going to hit that goal by 2015? I don't know that we're going to do that. One of the things I've learned in life is if you don't set a high enough goal, you'll certainly never come close to it." (Behind him, a copy of Benjamin Barber's

If Mayors Ruled the World is displayed on his desk. In a 2012 interview with the

Bay Area Reporter, Giuliano quipped, "Being mayor of San Francisco is a great gig, I wouldn't mind that.")

The centerpiece of the SF AIDS Foundation's 2014 plan will be the ribbon-cutting for a new, $10 million gay men's health and wellness center in the heart of the Castro. An architectural rendering is propped against the whiteboard in Giuliano's office. It shows a glass-fronted cube inviting passersby into an interior of recessed lighting and Scandinavian furniture.

The facility, at 474 Castro St., will consolidate three separate agencies: Magnet, a sexual health clinic; the Stonewall Counseling Center; and the STOP AIDS prevention office. Its location in the Castro is a tactical move that acknowledges the city's disproportionately high percentage of HIV-positive gay and bi men: 80% of the total HIV-positive population, by some measures. "There's still a balance of maybe 60/40 gay and bi men to the general population in most other urban areas," Giuliano says, a ratio that makes it difficult for other cities to hone treatment strategies. This is another reason why San Francisco has an edge when auditioning outreach initiatives: It's a lot easier to monitor medical and behavioral intervention if your clientele is homogenous.

Still, neither the San Francisco AIDS Foundation nor the city itself denies that a variety of factors--including crystal meth and bareback sex--continue to spur infection in new communities. The average profile of a new HIV case in San Francisco is a gay, 34-35-year-old white man, but African Americans are increasingly at risk. That said, the city's population is only 6% black, so that risk must be kept in perspective. San Francisco is nowhere near the emergency levels of Baltimore, Atlanta, or Washington, D.C., cities where black women in particular contract HIV at rates five times the national average. For Giuliano, the only plan that makes sense is a holistic health and wellness model that precludes fear. "The approach 10 years ago was 'wear a condom, wear a condom.' We're way beyond that now," he says.

San Francisco's progressiveness can't disguise a number of systemic flaws. Many of these aren't unique to the city but are byproducts of America's ramshackle economy, marked by income inequality, housing shortages, and unemployment. Michael Scarce, an activist and medical sociologist who has written two books about sexual politics, argues that these are the real blockades in San Francisco's quest for a cure. "If you could choose one city that would be the first to become AIDS-free it could very well be San Francisco," he says, "and yet all of the comorbidities and socioeconomic factors that intersect with HIV would need to be eliminated, if we're going to truly be AIDS-free. I don't know of that ever happening in the history of Western civilization." High on the checklist of hurdles are poverty, substance abuse, and homelessness. "We can provide testing and treatment all we want," Scarce tells me, "but if people at risk aren't inspired and motivated to have lives worth living we can't convince them to take advantage of something that might save their lives."

Scarce has the bemused but edgy tone of someone who has made it out of the woods. "I'm not interested in body counts anymore," he says, alluding to his own history of AIDS, drug addiction, and homelessness. Even now, he works two part-time jobs unrelated to his field and is trying to land a steady research gig. Three months ago he was served an eviction notice. He is burned out by PR buzzwords. "How are you going to save me if you don't even know me or what my life is like? How are you going to help me get well? I'm not sure that I want to be saved. I just want a chance to save myself, and that's a big difference."

When asked what his ideal outreach model looks like, he replies that he'd like to see policy makers live a day in the life of someone with AIDS. Short of that, he'll settle for more peer-based programs that actually administer to people with AIDS. In 2010, Scarce was interviewed by a French organization called the Warning. He used the opportunity to lambast the lack of transparency and general malaise among HIV/AIDS organizations and lobbied for the creation of a national watchdog agency. "In terms of fund- ing, Crisis = Money. Disease = Money. Risk = Money. The more AIDS organizations can portray their communities as unhealthy, sick, and high risk, the more they are rewarded financially and politically," he said in the interview.

This is as good a time as any to point out that according to Charity Watch's 2013 ratings guide, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation scores a C for how much it spends on programs and how much fundraising is required to raise $100. The foundation has the lowest grade of the eight AIDS organizations that are measured. There is also the matter of Neil Giuliano's salary: $270,000 in 2012. The executive team, which in 2012 included seven members, earned a combined income of more than $1.3 million. The salaries are modest in comparison to some other nonprofits, but could they hint at a larger disconnect between organization heads and those they'd help? "When you talk about a 25% reduction in new infections, I start to zone out," says Scarce. "A year from now I'm more worried about

Am I going to have an apartment?"

In 2013, San Francisco's housing market became the most expensive in the nation, with a median rent of $3,414. There was an 8% rent spike during a single quarter. Anxiety is palpable among long-time residents, especially since the past three years have also seen a 170% hike in Ellis Act evictions, which give retiring landlords carte blanche to evict their tenants. Gallons of ink and acres of bandwidth have gone into dissecting the city's run- away gentrification, but little has been said about what it portends for San Francisco's HIV/AIDS community.

Scarce sees the city's elitism as just another reason he'll fall through the cracks. "The city is still really behind wrapping its mind around homelessness," he says. "When you don't have a home, how are you supposed to get clean? How are you supposed to take your meds on a regular basis? How are you supposed to see your provider? And do you even want to do any of those things at that point?"

San Francisco is now in the uncomfortable position of having a cure within reach while being unable to offer it to many of the people who made it possible. It's a bittersweet proposition. It's also one that implicates front-line workers--nurses, benefits counselors, treatment advocates, case managers--who are often the lowest paid and most overworked. Scarce singles out Ellen at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation for special commendation: "God, I don't know if I'd be here if it weren't for her. She helped me and so many people I know in ways that are just mind-boggling. But you're not interviewing Ellen. That's not a criticism of you, it's just the system."

But should it be a criticism of anyone who presumes to talk about HIV/AIDS policy without first understanding the lives of people in the trenches? Politicians, CEOS, scientists, and researchers are all essential to orchestrating effective care, but their priorities, however well-intentioned, are generally light years away from those of people in the community. The story of HIV/AIDS is one that began on the street, and will hopefully end there as well. Whether a cure is discovered in San Francisco or some other charmed place, a happy ending is where the real demands of salvation must begin. "Personally," says Scarce, "I would not want to be in San Francisco to hear champagne corks popping all over the city when seroconversions end and I'm living with AIDS on the street."

CORRECTION: The print version of this article and the previously posted online version erroneously reported that Timothy Ray Brown, the "Berlin" patient, had relapsed from his functional cure of HIV. The Advocate regrets the error.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes