HIV

What Life Would Have Been Like Without ACT UP

What Life Would Have Been Like Without ACT UP

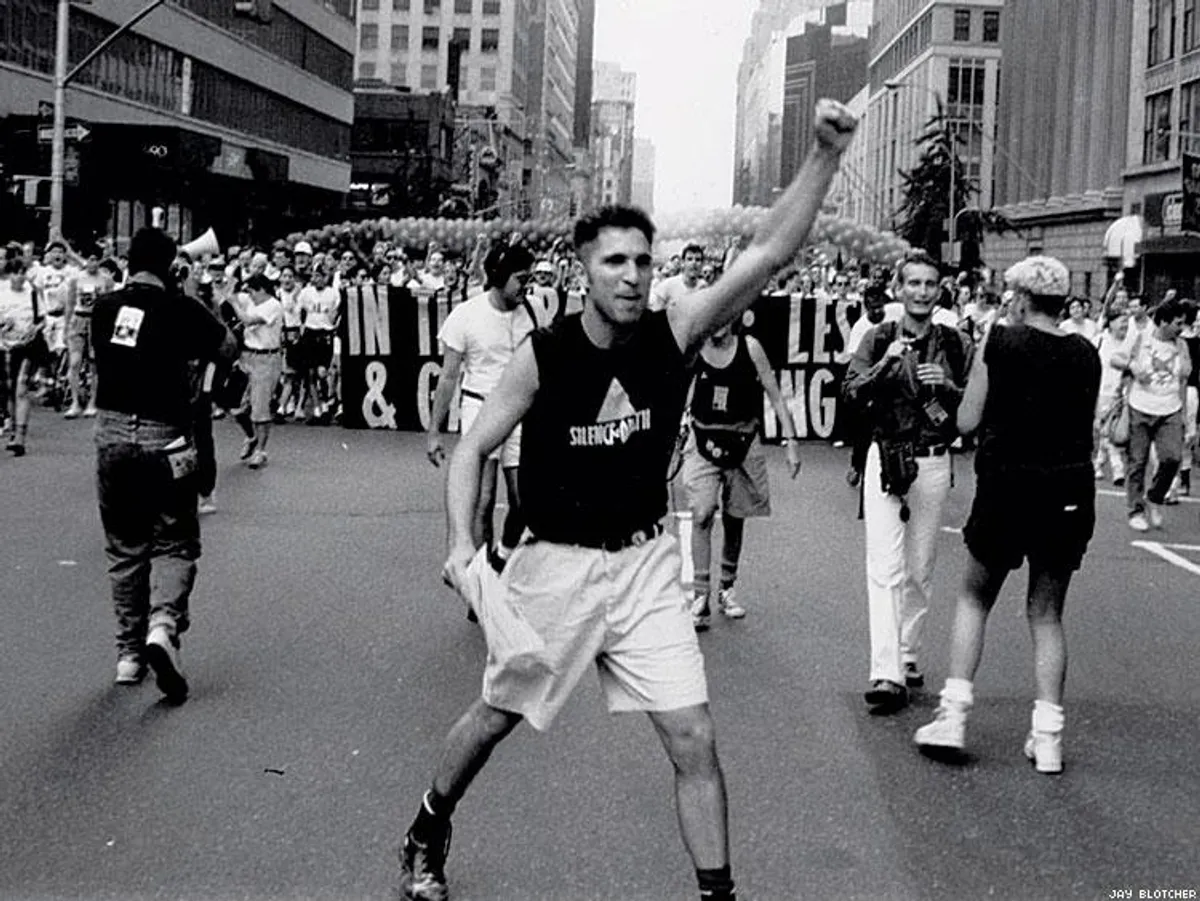

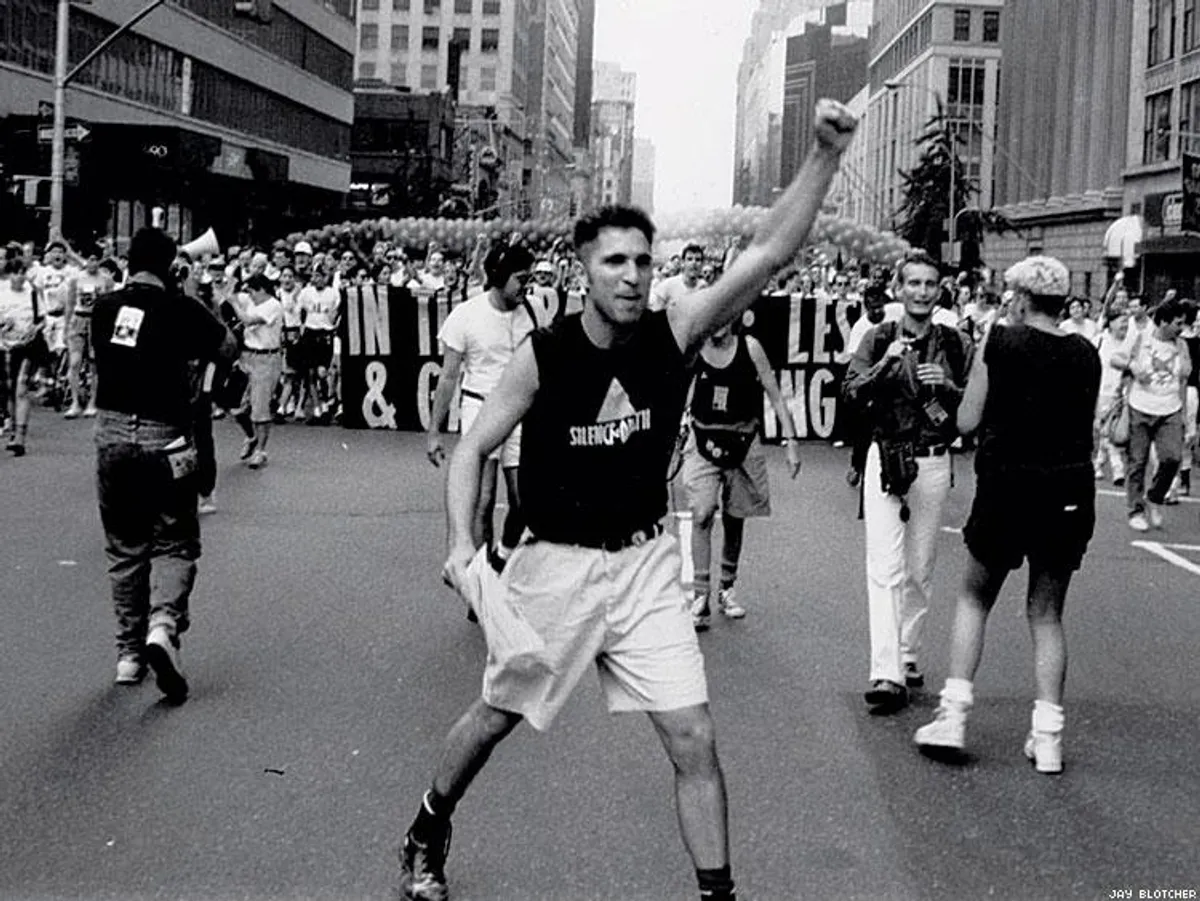

Matthew Ebert wonders what might have become of him, had he not joined ACT UP in 1987.

Matthew Ebert

November 09 2015 6:31 PM EST

May 26 2023 2:51 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

What Life Would Have Been Like Without ACT UP

Matthew Ebert wonders what might have become of him, had he not joined ACT UP in 1987.

It was late fall; I had heard about ACT UP from a lover -- a tall, lanky man who succumbed to AIDS a few years later. Driving my decision to join ACT UP at age 23 was a need to meet men and women interested in something other than bars, booze, and dance music. I had nothing against those things, but I wanted something more, something to connect with my soul.

In the summer of 1987, I was a demolition worker. I would pick up a rotary hammer drill, grab a bit, and drive holes into concrete walls. My shoulders widened, and at the end of the day my tanned arms and face would be covered with sweat and dust. A cream-colored mask of masculinity and brute force -- that was how I looked, late in August, when I drove an hour south to Rockland County and took my first ELISA immune response test. The nurse took hold of my arms, and she admired my veins -- she assured me that I would be OK. But I wasn't OK. I was petrified. I had been sexually active since I was a boy. I was molested as a young child. I had my first real boyfriend at 13. As an older teenager, I hustled. This culminated in a professional sex worker career by age 18. There was never a time in my life, since age 4, when I was not at high risk for HIV. I rolled north out of Rockland County in tears, and I cried agonized and bitter salt all the way home.

Back then it took four horrible weeks to get the results. I had gone to art school, and I had already known several men who fell to AIDS. Here's what it was like: They would call me up and tell me they were sick, I might see them once more, but more often, they secluded and removed themselves from impolite society. Six months to a year later, I would learn they were dead. Sometimes, I would get a letter. These letters I would burn, because I was not yet out to my family. Today, I wish I had saved those letters. They are as painful to me as letters from children who lost a family member on 9/11 -- the notes pinned to chain-link fences, with photos: "Please God, bring him home."

In one letter, a young man wrote to say he loved me, and he was sorry he let me go. He was sorry for being cruel. And I remember thinking that I had loved him too, passionately, but I had already forgiven us both, and I wished I could tell him. So I wrote him back, and I said how sorry I was, and I asked if I could drive up to see him in the college town where he lived. There was no word for weeks, until one day a letter arrived from his mother, telling me that he was gone. There was a picture enclosed, it was both of us, taken in a photo booth in Seaside Heights, NJ, in the summer of 1985. Black-and-white, four images on one strip of Kodak paper -- we kissed, we made stoic faces, we made goofy faces, and in the final frame we relaxed, and in our eyes you could see the wisdom beyond our years. What you could not see in those pictures was the future. In the future, one of us would be gone.

All this I burned. I burned my past when I walked into the Gay & Lesbian (now LGBT) center on West 13th Street that night in 1987. I was no longer a child, and I could not carry the weight of any more ashes. I took to the room, and the energy and the passion of activism, and the beauty of men and women fighting for our lives, for health care rights, for our civil rights. I learned how to protect myself from AIDS. And I learned what to expect from myself. I learned to rise above, because we were so loathed by the community and the world. We forget that. We forget that ACT UP was universally decried. My own gay brother pointed a finger at me and wagged it like an old man's cane, then crustily denounced me for taking away the dignity of another man's death. I wanted to show him the black-and-white photo booth portraits, but all I had was ashes in my hand.

I have my memories. There are good ones, and there are sad ones too. They keep me awake at night, and some days when I walk through New York City, I feel as if I'm roaming in a meadow of ghosts. This is not the rough-and-tumble city of my youth. And the places I used to haunt are now paved over with gold and glass. AIDS behind glass -- we remember it now as a kind of artistic movement, and not a sacrifice, not an epidemic. By doing so, we perpetuate the myth that the epidemic is over -- and it isn't over. I believe we won't know true liberation until it is.

Had I not joined ACT UP in 1987, and continued to this day to be a card-carrying ACT UP member, I would be dead. When I ask myself, "What would my life be like without ACT UP?" -- the answer is uneasy. There would be two of us in that photo strip, now 30 years gone, blowing downwind of the ashcan like so much yesteryear debris and grit memory. I would be the wind and the empty page, the words I would never write, and there would be no one left to remember my name.

MATTHEW EBERT is a writer, agrarian, rural proponent, artist, and activist.