Queer coding of characters in literature, television, and movies can be seen as a good thing. These are characters who are not portrayed explicitly as queer but exhibit characteristics that suggest (whether the creators intend it or not) that a character is queer. Queer coding is usually distinguished from queer baiting, in which characters are intentionally coded as queer to lure in queer audiences. Still, the potential queerness is not realized in the lives or relationships of the characters in any fulfilling way.

Even though queer coding is the more positive practice, it has an important and, in some ways, problematic history. As the term is generally used, queer coding captures only a part of what it means to be coded as queer and not even the most essential part.

Beginning in 1934, queer coding was the only game in town for queer representation in Hollywood movies because the movie industry was forced to follow the Hays Code to ward off external regulation. Among many other requirements, the Hays Code forbade queer characters from being portrayed in a positive light. In practice, this meant one of two things: either characters intended as queer had to be subtly portrayed with just hints of stereotyped identity and desire, or they could be slightly more blatantly portrayed if they were cast as villains.

For example, the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz (1939) is often cited as a queer-coded character. Film expert Derek Le Beau explains that the actor who played the Lion based his performance on "effeminate gay stage and screen characters known as sissies, or pansies" by having the character engage in several 'gay' actions like blushing when he gets a kiss on the cheek from the Wizard. He also reports the director of The Maltese Falcon was warned by the Hays Office about how the villain Cairo, who is gay in the original Dashiel Hammett novel, would be portrayed. The director was advised not to "get a 'nancy' quality into him." Le Beau explains that the director coded the character queer "by giving Cairo a dandyish appearance, complete with a fancy pair of gloves, a pinky ring, a cane cleverly used to signify a phallus–and gardenia-scented calling cards (originally lavender, but the Hayes office objected)."

Historically, queer coding can be read as a creative and positive response to systemic attempts to erase the existence of queer people in an essential cultural platform, and the practice has continued beyond the end of the Hays Code in the 1950s and extends beyond movies. Queer scholars point to a host of queer-coded characters in TV and the film, such as Matron "Mamma" Morton in Chicago, Tom and Jerry in a BDSM relationship, and Bugs Bunny appearing about fifty times in drag.

Despite this positive contribution to the inclusion of queer characters, queer coding has been problematic in two ways. First, too often, it depended on narrow stereotypes of queer people as effeminate gay men or butch lesbians, ignoring the range of roles and gender expressions queer people inhabit. Second, the culture created by the Hays Code seems to have led to many queer characters being cast as villains. Just look at the dominant pattern of queer representation in queer-coded Disney villains such as Scar, Captain Hook, Jafar, Governor Ratcliffe, and Ursula.

Direct positive queer representation has significantly improved since the late-90s, and queer coding has correspondingly evolved to be more inclusive. It remains a meaningful way to represent various aspects of closeting that queer people must still negotiate.

Instead of queer coding, we need to understand what it means to be coded as queer.

The underlying principle is the same: someone is seen as queer through a set of behaviors without a queer label being explicitly attached. However, being coded as queer with or without our consent has a broad range of real-life effects, and examining this phenomenon reveals two crucial lessons that can help us to untangle ourselves from the tentacles of anti-queer cultural violence that continue to plague our society.

Many of us are coded as queer by family, friends, classmates, teachers, clergy, employers, and strangers long before we are ready to come out of our closets as well as throughout our lives by people to whom we are not explicitly out. When I applied for my first professional job as a writing tutor at the local university, I told the lovely woman interviewing me I wanted to try something new because becoming a missionary had not worked out for me. I was over a decade away from saying that I was gay, but she knew at that moment; fifteen years later, when I came out professionally in an article, she wrote to me to say that in that interview, she mentally added, "Of course not, because you're gay" to my explanation. When I finally came out in my late 30s, I discovered that for many in my life, my homosexuality was not a surprise.

Like many queer people, I had been living in a mostly glass closet and had been coded as queer for nearly all my life.

When we are coded as queer, we are not doing anything wrong. Instead, we express ourselves in ways that have been made problematic according to sets of values intended to marginalize and diminish us. Not all efforts to code me as queer were as benign as my kindly interviewer or some family and friends waiting for me to be ready to claim my gay sexual identity. Coding often took the form of homophobic slurs in locker rooms or injunctions to follow gendered rules about such meaningless things as how I crossed my legs or how I walked. Being coded as queer may or may not stem from ill intent, but it is never a neutral act.

From the time I came out in the late 90s, queerness has become more expansive and inclusive than what was represented in the overly simplistic queer coding in movies and television. In my lifetime, the term queer has been reclaimed from its use as a slur to be a catch-all term for all the letters of the LGBTQIA+ alphabet as well as to include those who identify as non-binary or as gender expansive.

Although things have improved for queer people in the last fifty or so years, we are far from full equality and acceptance, and our increased visibility on our terms has been met with considerable backlash. We barely had a term for gender-affirming care before Republican-controlled state legislatures started drafting legislation to ban it, as transphobia runs rampant in many conservative states and communities. Also, among the many horrors of Project 2025 are proposals to allow schools to out queer students to their parents and define sex as only biological sex assigned at birth. In this context, understanding how we are being coded as queer is a critical means of resistance.

Understanding that we have been coded as queer and can, to some extent, re-code ourselves on our terms does not magically make everything better. However, the existence and use of more inclusive queer terms recognize that we are more than what we have been thought to be and that we have the right to define ourselves.

Understanding how coding us queer helps us to know that we are not the problem, that we are not alone, and that we can make intentional choices about how we understand and present ourselves.

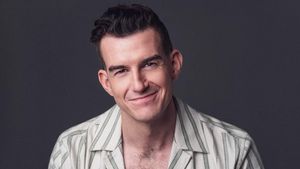

David L. Wallace is a professor of English at Long Beach State University, and he has published a number of articles about the effects of closeting on queer people. He lives in West Hollywood, CA, where he spends as much time as possible swimming laps, hiking, running, cooking good food, reading mystery novels, and joining friends for happy hour.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit advocate.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists and editors, and do not directly represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, equalpride.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes