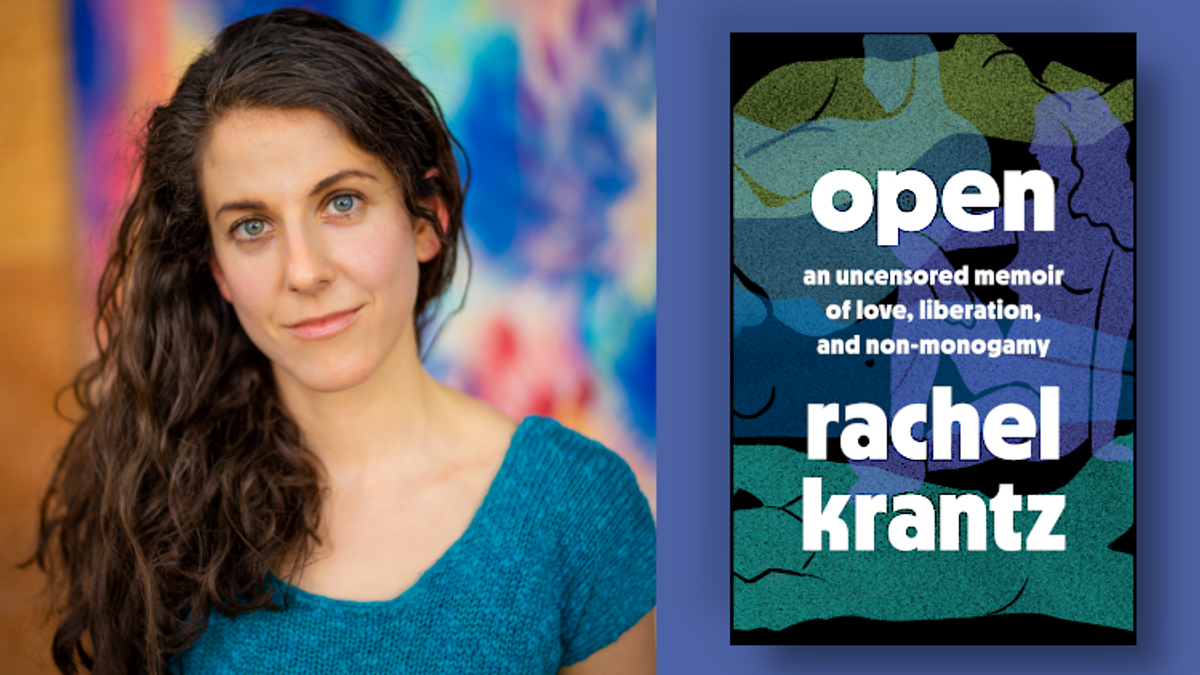

Open, a new memoir from Rachel Krantz, is not simply the documentation of a period of intense self-discovery for the author. It's the story of a journalist who, while coming into her queerness, spent half a decade researching and reporting on nonmonogamy.

Relationship styles, much like sexuality, exist on a spectrum. Some of us are extremely oriented toward open relationships, some are not. Many are somewhere in the middle, leaning toward one end or the other. But as Krantz points out, how are you supposed to parse out where you fit on that spectrum when all of the external messages that we receive from birth point to relationships, successful or not, as being between two people only?

"What is the discomfort of growing beyond paradigms that I've been socialized to think are acceptable and normal, and what is the discomfort of extreme jealousy and anxiety in a relationship that's maybe not healthy?" Krantz asks on this week's LGBTQ&A podcast. "I found, at least for me, there's probably no limit to the amount of people I could love."

With the publication of Open, Krantz is challenging both readers and journalists to engage with her book as they would any other work of immersion journalism, moving beyond expected tropes of "confessional erotica" with which a woman writing about her sex life is often classified. "I am an investigative journalist and a sexual being, and those two identities shouldn't negate each other," Krantz says. "Why is this something that's potentially considered untouchable or risking ruining my career by admitting these things about my sexual psychology on the record when I have serious journalism to back it up?"

Krantz joins the LGBTQ&A podcast to talk about how to best deal with jealousy in open relationships, the internalized biphobia that remains pervasive in our culture, and her new book, Open: An Uncensored Memoir of Love, Liberation, and Non-Monogamy (out now).

You can listen to Rachel Krantz on the LGBTQ&A podcast and read excerpts below.

Jeffrey Masters: You write about the stigma that exists around non-monogamy. When you were first starting to explore it, how were you able to parse out what discomfort you were experiencing was due to stigma and what was due to nonmonogamy possibly not being right for you?

Rachel Krantz: That was part of my confusion. It was like, "What is the discomfort of growing beyond paradigms that I've been socialized to think are acceptable and normal, and what is the discomfort of extreme jealousy and anxiety in a relationship that's maybe not healthy?"

A lot of people find themselves in that situation when they're exploring nonmonogamy or kink or maybe even when they're coming into their queerness, which are all also things that were happening to me during the time period of the book, and it can get very confusing because you're like, "Am I uncomfortable because this isn't right for me and because this is an unhealthy dynamic or maybe we're not practicing these things in an ethical way, or is it because I'm just experiencing a totally new way of being that society often still shames?"

You ultimately discovered that you're extremely oriented toward nonmonogamy. Did you feel that right away?

It did feel really right once it was introduced. At least on my end, it felt very natural. But where it didn't feel very right, in the beginning, was once it was a situation like, "OK, you can dish it out, but can you take it?" Experiencing my partner going out with other people and feeling jealousy around that for the first time, that part of it did not come easily to me. I did not find I was the model polyamorous girl who's just like, "Oh, it's all great. I'm feeling so much compersion." I was like, "I want to cut a bitch." I was so jealous.

Part of that was about the dynamic I was in where it was also a very dom-sub relationship, most of which was uncommunicated. That put me in a difficult position where I was more prone to jealousy just because I felt so powerless. But on my end, it did feel very right. Like, "Oh, yeah. Of course, there's multiple people who I love, multiple figures and different sides of myself that want to be expressed."

What tools have you found that are helpful to deal with and live with that jealousy?

I think meditating, learning to meditate proved incredibly helpful because you're learning to sit with extreme potential discomfort and letting go of your ego in certain ways. Protecting your ego.

Then finally just finding healthier relationship dynamics where I felt like I had more of a say, more of a sense of equality, and it wasn't someone else steering the situation so completely has also helped me feel much less jealous, just because I don't feel so powerless.

Is jealousy the biggest hurdle, or are there larger challenges we don't think about?

Definitely jealousy was one of the main ones and anxiety around that. Now what I find is difficult is something that was also happening when I first started dating people on my own, which is that it's much easier to fall into relationships with people who are themselves looking for a primary partner or aren't sure that they really want to be in a nonmonogamous situation. Then you can end up with them keeping you at arm's length or dumping you once they find someone they want to be monogamous with. It's difficult because I've fallen in love with people who it kind of ends in an abrupt way when they find someone else to be monogamous with.

I found, at least for me, there's probably no limit to the amount of people I could love. The more I open, in fact, the easier it is to love because you see how there's so many different forms it can take and you're not trying to fit people into one box of what a love relationship can look like.

You tweeted, "Serious journalists, i humbly implore you to consider taking me and my book seriously. Over five years of research & reporting went into writing OPEN. Just because it's also sexy and entertaining doesn't mean it isn't a piece of investigative journalism as well." Is that a fear you have, that this is not going to be taken seriously?

I feel a little bit better than when I tweeted that because I'm starting to have meaningful conversations with journalists I respect like this and I can tell they're engaging deeply with the book.

Like I say in the book, why is a man climbing Everest considered award-winning journalism, which is the book Into Thin Air by John Krakauer, while a woman writing about her sex life and plumbing her most extreme psychosexual depths is confessional erotica?

I think there is very much that binary still and hesitance in our culture to talk about these things in a way that doesn't put them into a box of just being salacious or silly or light or women's issues. It's a big part of the political statement of my book: No, I am both those things. The Madonna-whore binary is false.

I did over five years of reporting and research and serious immersion journalism in living this story, dozens and dozens and dozens of interviews. Even though it's a true story, it's going to be sexy and compelling, and both those things are not contradictions. I am an investigative journalist and a sexual being, and those two identities shouldn't negate each other. Why is this something that's potentially considered untouchable or risking ruining my career by admitting these things about my sexual psychology on the record when I have serious journalism to back it up?

I'm feeling hopeful. I feel like the conversations I'm beginning to have, people are really ready to let that coexist.

Regarding your bisexuality, you wrote that there's "a certain idolization of queerness I'm dangerously prone to. As if being with women is somehow more evolved or interesting than being with men. As if women who don't at least try being with other cis women, trans people, or nonbinary folks are simply fearful of fully understanding themselves."

Absolutely. It was important for me to point that out and how I've continued to wrestle with that since because I think a lot of it was also about my internalized queer impostor syndrome and biphobia and feeling like I have always been attracted to women and people who are nonbinary or trans. I'm attracted to people of all genders, but my dating history is much heavier on dating cis men. There are many reasons for that, and one of them was the narrative in those subcultures I was around that were more liberal kind of dismissing bisexuality as like, "Yeah, but everyone's kind of gay, right?" or like, "Yeah, certain women who are just open to exploring," which I knew myself to be, "are just kind of like doing that. They're exploring. That's not really an identity, right?"

So I, for so long even after I started having romantic and sexual experiences with women, didn't feel like I had the right to claim that label because I was like, "I've never been in a long-term committed partnership with anyone but a cis man, so what right do I have to say that and what right do I have to take up that space if I've had all this 'straight passing' privilege?"

I do think all of that has to be recognized and also addressed because that's real. I haven't experienced as much homophobia as most lesbians have, for example, but I also think that some of the internalized biphobia and real difficulty owning my own queerness came from well-meaning friends who were queer-shaming other women who were having experiences with them as just experimenting or using them for the experience, which granted, a lot of people do have that experience and I understand why they were annoyed by it, but I felt this sense of gatekeeping from my own friends of like, "That's not real or these women are just messing with us."

So I was like, "Oh, shit. I don't want to be one of those women, so I better not admit to being one of them until I can really say for sure or I can really prove it that I'm gay enough."

Open by Rachel Krantz is out now.

You can listen to the full LGBTQ&A interview with Rachel Krantz on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Brandi Carlile, Billie Jean King, and Roxane Gay. New episodes come out every Tuesday.

RELATED: Queer and Polyamorous in a Pandemic