Every Supreme Court decision that radically changed LGBTQ+ rights

06/26/24

trudestress

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

From left: Gerald Bostock; lawyers Ruth Harlow and Paul Smith; James Obergefell

Wikimedia Commons; Gerald Martineau/The Washington Post via Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images

The U.S. Supreme Court is hearing cases in this term that stand to affect LGBTQ+ rights. In December, it heard one concerning Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors. This week, it's hearing one brought by a woman who claims she suffered workplace discrimination because she's white and straight. The high court's rulings in both of these cases could set important precedents. The decisions will likely be released in June, toward the end of the court's term.

The court’s LGBTQ+ decisions have given our community cause for celebration as well as cause for despair. Here’s a look back at these rulings.

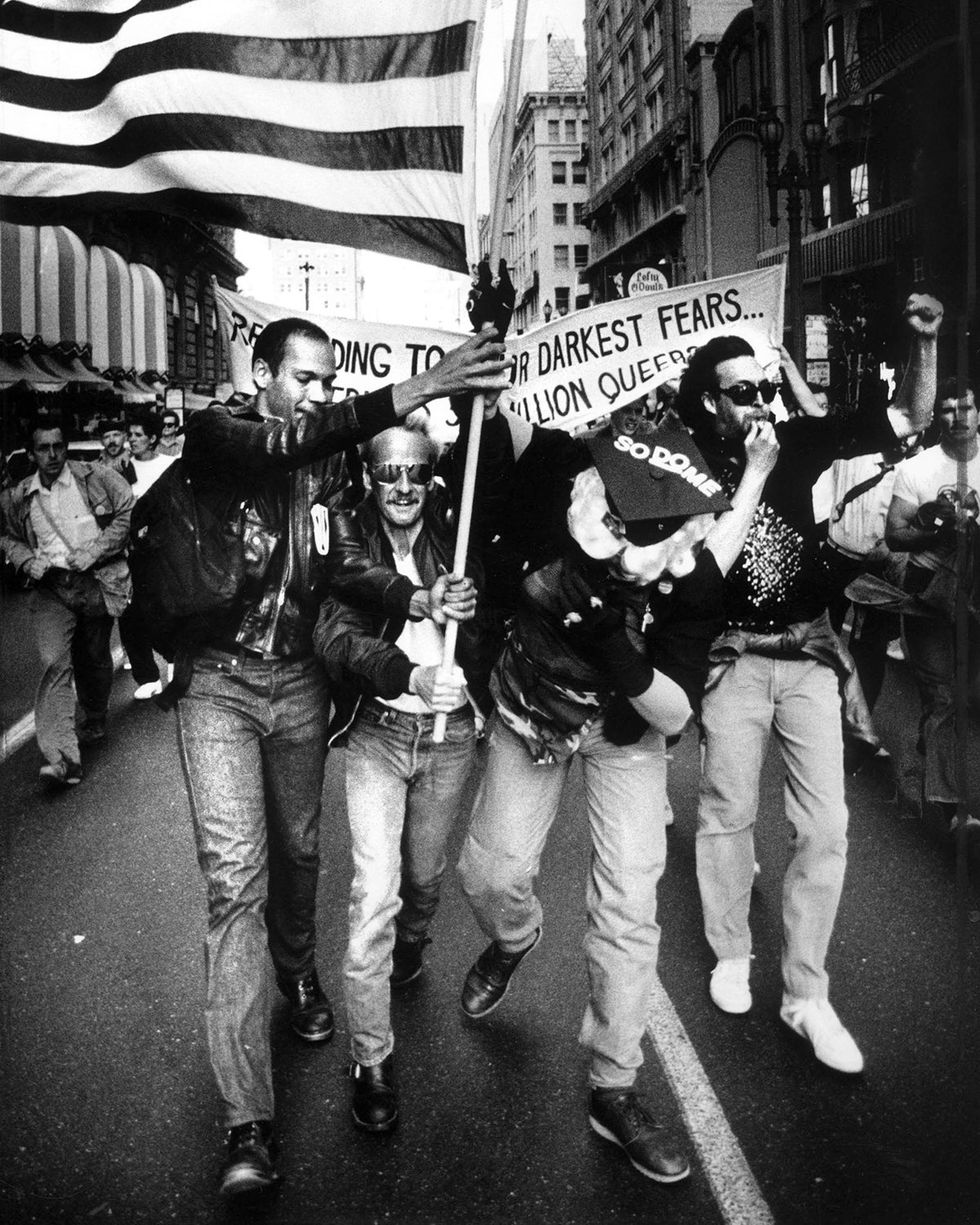

San Franciscans protest the ruling

Tom Levy/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

A Georgia man, Michael Hardwick, was charged with violating the state’s sodomy law by engaging in consensual sex with another man in the privacy of Hardwick’s home. A police officer had observed them while serving a warrant on Hardwick in an unrelated case. Hardwick challenged the constitutionality of the law, but the Supreme Court ruled against him, 5-4, upholding the Georgia law and similar ones in other states.

“The Constitution does not confer a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in sodomy,” Justice Byron White wrote for the court majority. “None of the fundamental rights announced in this Court’s prior cases involving family relationships, marriage, or procreation bear any resemblance to the right asserted in this case. And any claim that those cases stand for the proposition that any kind of private sexual conduct between consenting adults is constitutionally insulated from state proscription is unsupportable.”

That ruling would stand for 17 years.

Pam Berry/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The South Boston Allied War Veterans Council, organizer of the St. Patrick's Day-Evacuation Day Parade, declined to let the Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, or GLIB, march in the 1993 event. GLIB then sued, alleging violations of the Massachusetts and U.S. Constitutions and of the state public accommodations law, which banned discrimination based on sexual orientation “in any place of public accommodation, resort or amusement.” State courts, including the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, ruled in GLIB’s favor, saying that its inclusion would not violate the organizer’s First Amendment rights. But the U.S. Supreme Court disagreed.

“The issue in this case is whether Massachusetts may require private citizens who organize a parade to include among the marchers a group imparting a message the organizers do not wish to convey. We hold that such a mandate violates the First Amendment,” Justice David Souter wrote for the unanimous court.

In 2015, however, the council began letting an LGBTQ+ veterans group, OutVets, march in the parade. OutVets marched again in 2016, but in 2017 the council tried to bar the group, then ended up reversing its position.

There have been fights over LGBTQ+ inclusion in other St. Patrick’s Day parades, particularly in New York City. The Manhattan parade, which is the world’s oldest and largest, lifted its ban on LGBTQ+ contingents in 2014, but Staten Island’s parade still kept them out, with organizers saying an LGBTQ+ presence was not appropriate for an event honoring a Catholic saint. This year, there were two St. Patrick’s parades in the borough, one including LGBTQ+ marchers, one not.

New York Pride marchers protest Colorado's Amendment 2

Barbara Alper/Getty Images

In its first pro-LGBTQ+ ruling, the Supreme Court held 6-3 that Colorado’s Amendment 2 violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Colorado voters had approved Amendment 2 in 1992, changing the state’s constitution so that neither the state nor any local government could enact or enforce protections against discrimination based on “homosexual, lesbian or bisexual orientation, conduct, practices or relationships.” It didn’t address gender identity, something most people didn’t think of at the time. Several LGB Coloradans sued. State courts blocked enforcement of Amendment 2, and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed that the amendment was a bad idea.

“We cannot accept the view that Amendment 2’s prohibition on specific legal protections does no more than deprive homosexuals of special rights,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the court majority. “To the contrary, the amendment imposes a special disability upon those persons alone. Homosexuals are forbidden the safeguards that others enjoy or may seek without constraint.” Kennedy cited Justice John Marshall Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 high court ruling that upheld racial segregation. Harlan, the only dissenter, wrote that the U.S. Constitution “neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Kennedy noted, “Unheeded then, those words now are understood to state a commitment to the law’s neutrality where the rights of persons are at stake. The Equal Protection Clause enforces this principle and today requires us to hold invalid a provision of Colorado’s Constitution.”

The dissenters in the Romer ruling were, unsurprisingly, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and William Rehnquist. “The Court has mistaken a Kulturkampf for a fit of spite,” Scalia wrote. He called Amendment 2 “a modest attempt by seemingly tolerant Coloradans to preserve traditional sexual mores against the efforts of a politically powerful minority to revise those mores through use of the laws.” He cited the Bowers v. Hardwick ruling, which upheld “moral disapproval of homosexual conduct,” adding, “Amendment 2 is designed to prevent piecemeal deterioration of the sexual morality favored by a majority of Coloradans.”

Scalia remained opposed to LGBTQ+ rights until his death in 2016, while Kennedy (mostly) championed LGBTQ+ equality until his retirement in 2018.

Justice Antonin Scalia

Tom Williams/Roll Call

Scalia provided a surprise, however, in writing the opinion for the unanimous court in this case, which involved same-sex sexual harassment. Joseph Oncale, a straight man who worked on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, was harassed, physically assaulted, and threatened with rape by other male employees. Oncale took the problem to human resources but got no satisfaction there, and he eventually quit and sued Sundowner. “I felt that if I didn’t leave my job, that I would be raped or forced to have sex,” he said in a court deposition.

The high court agreed that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits sex discrimination in employment, banned discrimination and harassment by members of the same sex as well as the opposite. “We hold today that nothing in Title VII necessarily bars a claim of discrimination ‘because of ... sex’ merely because the plaintiff and the defendant (or the person charged with acting on behalf of the defendant) are of the same sex,” Scalia wrote.

The decision was seen as positive for workers of all orientations. “In the beginning all my client ever wanted was his day in court,” Oncale’s attorney, André LaPlace, told The Advocate in 1997 as the Supreme Court prepared to hear the case. “He started out living a very closed existence, not having much contact with gay people. But during this process he has learned what gay people face in terms of discrimination: If his case can help them out, he’s happy about that.”

The court would revisit the meaning of Title VII again in 2019 and rule on it in 2020. More about that later.

From left: James Dale and lawyer Evan Wolfson

Stephen Boitano/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images

There wasn’t unchecked progress for LGBTQ+ rights at the Supreme Court. There were several court challenges to the Boy Scouts’ ban on gay and bisexual Scouts and leaders, put in place in 1978 (perhaps the BSA hadn’t considered the possibility before), and the one that went all the way to the high court was brought by James Dale, a New Jersey man who was removed as an assistant scoutmaster when the BSA and its local council learned he was gay. (Or, as then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist put it in his Supreme Court ruling, “an avowed homosexual.”)

Dale argued that the BSA was violating New Jersey’s law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in public accommodations. But the Supreme Court found, in a 5-4 ruling, that being forced to accept gay or bi members and leaders would interfere with the Scouts’ “freedom of expressive association.”

The BSA eventually came around. It lifted the ban on gay and bi youth members at the beginning of 2014, and in 2015, it decided to allow gay and bi adult leaders, with the caveat that church-sponsored troops could still exclude anyone who offended their religious sensibilities. In lifting the ban, the Scouts cited “the rapid changes in society and increasing legal challenges at the federal, state, and local levels.” In 2017, the BSA announced that it would accept girls and transgender boys, and it recently announced that organization will change its name next year to Scouting America, yet another move to stress that it has become an inclusive group.

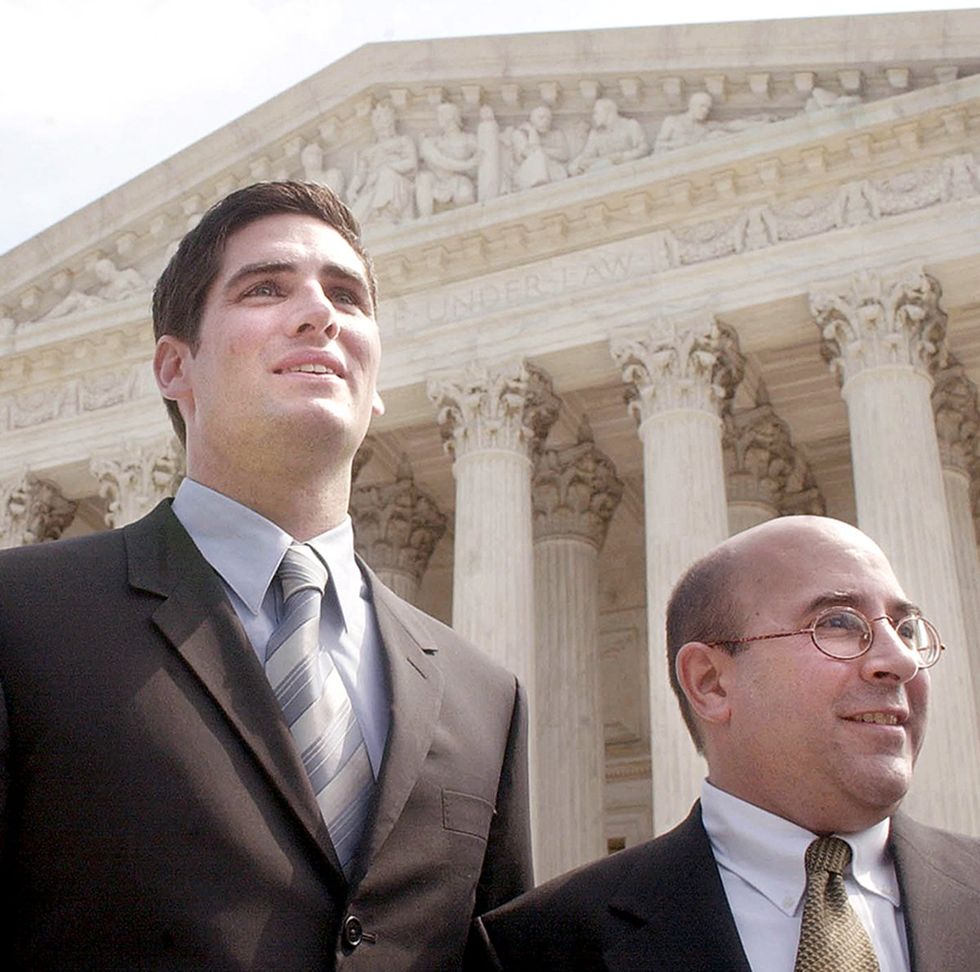

Lawyers Ruth Harlow and Paul Smith, who argued for LGBTQ+ rights in Lawrence v. Texas

Gerald Martineau/The Washington Post via Getty Images

In Lawrence v. Texas, the high court reversed the stand it had taken in Bowers v. Hardwick. It struck down Texas’s sodomy law and all remaining ones in other states. “Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today,” Anthony Kennedy wrote for the 6-3 court majority. “It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

The Lawrence case did not involve minors, public conduct, or government recognition of same-sex relationships, Kennedy noted. “The case does involve two adults who, with full and mutual consent from each other, engaged in sexual practices common to a homosexual lifestyle,” he wrote. “The petitioners are entitled to respect for their private lives. The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime. Their right to liberty under the Due Process Clause gives them the full right to engage in their conduct without intervention of the government.” He also pointed out that society had changed since Bowers and the number of states with sodomy laws had dwindled, and he cited Supreme Court decisions asserting the right to privacy in contraception and abortion. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who had joined the majority ruling in Bowers, wrote a concurring opinion saying she did not believe Bowers should be overturned, but she agreed that the Texas statute should be struck down because it applied to same-sex liaisons but not those involving different sexes.

The dissent came from — surprise! — Scalia, Thomas, and Rehnquist. Overruling Bowers, Scalia wrote, is “a massive disruption of the current social order.” He denied that overruling Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision affirming abortion rights, would be a similar disruption — on which many would differ, but Scalia was had been dead for six years by the time Roe was struck down in 2022, so no one could confront him then. He also said sodomy laws were based on “society’s belief that certain forms of sexual behavior are ‘immoral and unacceptable,’” and that was OK by him. He predicted that overturning Bowers would lead to legalization of bigamy, which hasn’t happened, and of same-sex marriages, which has — more about that soon.

Edie Windsor

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

In another momentous June 26 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the main portion of the Defense of Marriage Act, which was passed in 1996 and denied federal government recognition to same-sex marriages. Lesbian widow Edie Windsor decided to challenge the law; she was represented by Roberta Kaplan, a lawyer who has become legendary for her civil rights work.

Windsor and Thea Spyer became partners in the 1960s and were finally able to marry in Canada in 2007. But the U.S. did not recognize their marriage, with the result that when Spyer died two years later, Windsor owed $363,000 in estate taxes — which she would not have owed if she had been married to a man. Surviving spouses are exempt from the tax, but the law defined “spouse” only in opposite-sex terms. So she sued.

Federal district and appeals courts ruled DOMA’s section 3, which dealt with federal government recognition, to be unconstitutional, and in 2013 the Supreme Court agreed. The Obama administration’s Department of Justice refused to defend the law; President Obama and Vice President Biden had both come out for marriage equality the previous year. So Republicans in Congress hired conservative lawyer Paul Clement to defend it. He didn’t succeed.

“DOMA violates basic due process and equal protection principles applicable to the Federal Government,” Justice Kennedy wrote for the 5-4 majority. “The Constitution’s guarantee of equality ‘must at the very least mean that a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot’ justify disparate treatment of that group. ... DOMA cannot survive under these principles.”

States remained free to deny recognition to same-sex marriages performed in other states, but the decision striking down section 3 meant that same-sex married couples had access to a wide array of federal benefits.

Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Samuel Alito dissented. The majority ruling, Scalia wrote, “is an assertion of judicial supremacy over the people’s Representatives in Congress and the Executive.”

Sandy Stier, Kris Perry, Paul Katami, and Jeff Zarrillo

Jewel Samad/AFP via Getty Images

The same day it issued the ruling in United States v. Windsor, the Supreme Court struck another blow for marriage equality. It let stand a lower court’s ruling striking down California’s Proposition 8, a state constitutional amendment passed by voters in 2008 to revoke marriage equality.

The California Supreme Court had ruled for marriage equality in May 2008, but when voters passed Prop. 8 in November, amending the state constitution overrode the ruling. Two same-sex couples, Kris Perry and Sandy Stier, and Paul Katami and Jeff Zarrillo, sued over Prop. 8 after they were denied marriage licenses. A new activist group, the American Foundation for Equal Rights, funded the legal challenge with famed lawyers Ted Olson and David Boies — the two attorneys who argued opposing sides of Bush v. Gore in 2000.

U.S. District Judge Vaughn Walker ruled in 2010 that Prop. 8 violated the U.S. Constitution. California state officials in two consecutive administrations declined to defend Prop. 8, among them Kamala Harris, elected California attorney general in 2010. So a conservative group called ProtectMarriage.com took up the defense, and the case was named for one of its leaders, California Republican politician Dennis Hollingsworth.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld Walker’s ruling in 2012. It had also declined to vacate his decision on the grounds that Walker is gay. So ProtectMarriage.com appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled 5-4 that the group did not have what’s known as “standing” to appeal — that is, it hadn’t shown that its members were harmed by Walker’s decision. “We have never before upheld the standing of a private party to defend the constitutionality of a state statute when state officials have chosen not to. We decline to do so for the first time here,” Roberts wrote for the majority.

The high court’s decision didn’t fall along ideological lines. Roberts was joined by fellow conservative Scalia and liberals Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Elena Kagan, while Kennedy authored a dissent, in which he was joined by two conservatives, Thomas and Alito, and liberal Sonia Sotomayor. Kennedy didn’t argue for the merits of Prop. 8, but he said private groups like ProtectMarriage.com did have standing to defend the measure when the state wouldn’t.

James Obergefell

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Obergefell v. Hodges was the ruling that established marriage equality nationwide. Same-sex couples had been suing to strike down state marriage bans around the country, and they won at federal district courts in several states, including in Michigan, Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee, the states covered by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. However, the Sixth Circuit reversed that ruling, and the couples appealed to the Supreme Court. The named plaintiff was James Obergefell, an Ohio man who married his dying partner, John Arthur, in Maryland in 2013 because their home state didn’t allow same-sex couples to marry — and then Ohio didn’t recognize their marriage and wouldn’t list Obergefell as the surviving spouse on Arthur’s death certificate. The Hodges was Richard Hodges, an Ohio official.

Kennedy authored the 5-4 majority ruling. “The limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just, but its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest,” he wrote. “With that knowledge must come the recognition that laws excluding same-sex couples from the marriage right impose stigma and injury of the kind prohibited by our basic charter.”

With that, all remaining state bans on same-sex marriage were invalidated — in 13 states and Puerto Rico. LGBTQ+ Americans and their allies celebrated around the nation, and many same-sex couples quickly applied for marriage licenses.

Kennedy was joined by Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor. The dissenters were Alito, Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas.

Wikimedia Commons

After marriage equality became the law of the land, there were many arguments over whether private businesses had to recognize it — and if they could discriminate against couples or individuals who offended their religious beliefs. This case, out of Colorado, involved Masterpiece Cakeshop owner Jack Phillips's refusal to bake a wedding cake for gay couple David Mullins and Charlie Craig for their 2012 celebration in Colorado, following a wedding in Massachusetts. Phillips cited his Christian beliefs against same-sex marriage, and said creating the cake would violate his rights to freedom of religion and artistic expression. He had been willing to sell the couple other goods but not a custom wedding cake. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission had found the baker in violation of the state's antidiscrimination law, and Colorado courts had upheld its ruling, leading to a hearing in December 2017 at the U.S. Supreme Court.

The following June, the high court ruled 7-2 in favor of Phillips,in favor of Phillips, saying the commission had shown insufficient respect for his religious beliefs. "The law must be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion," Kennedy wrote for the majority. Both conservatives and liberals sided with him — Alito, Breyer, Kagan, Roberts, Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch, Donald Trump's appointee to succeed Scalia. Trump was able to nominate Gorsuch to the court because the U.S. Senate had refused to give a hearing to Obama's nominee to replace Scalia, Merrick Garland, in the last year of Obama's presidency. Ginsburg and Sotomayor dissented.

The ruling was considered a narrow one because the court's rationale was that Phillips was disrespected by the Colorado commission. It didn't establish a broad right to discriminate. However, LGBTQ+ activists worried that it would lead to rulings establishing such a right.

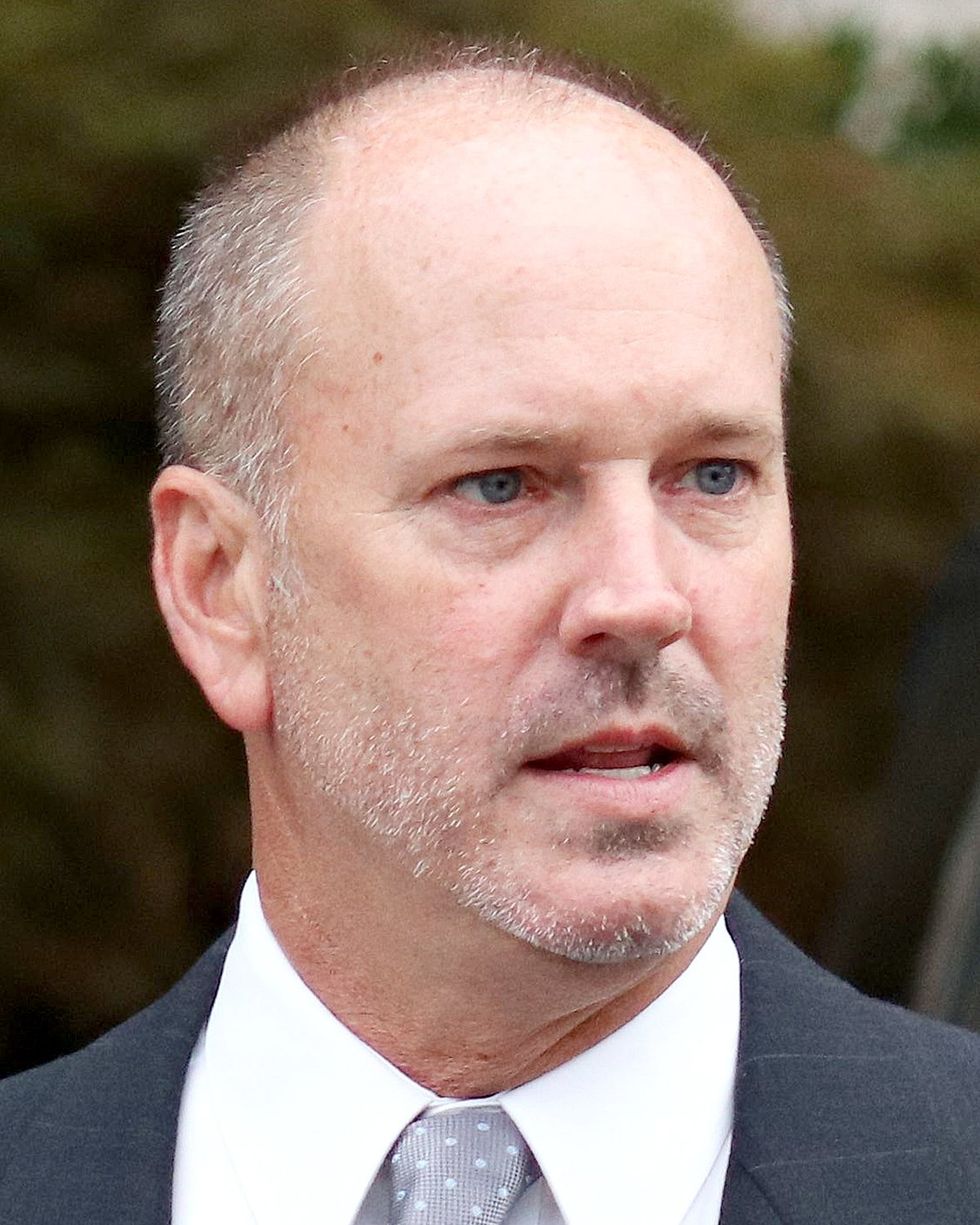

Gerald Bostock

Wikimedia Commons

In this landmark decision, the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans sex discrimination in employment, bans job discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

The ruling came in two consolidated cases involving gay men who were fired from their jobs -- Bostock v. Clayton County and Zarda v. Altitude Express -- and one involving a transgender woman who lost her job, R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The court heard oral arguments in the cases in October 2019.

The 6-3 ruling was written by Gorsuch. He was joined by another conservative, Chief Justice John Roberts, and the court's four liberals -- Ginsburg, Kagan, Sotomayor, and Breyer. Dissenting were conservatives Alito, Thomas, and a new Trump appointee, Brett Kavanaugh, who succeeded Kennedy after the latter's retirement.

"An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex," Gorsuch wrote, adding, "Only the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit."

The cases involved Gerald Bostock, a social worker in Georgia who was fired after joining a gay softball league; Donald Zarda, a skydiving instructor who was dismissed by a New York-based company after telling a client he was gay; and Aimee Stephens, a Michigan funeral director who lost her job after she came out as transgender and told her employer she would begin presenting as female at work. All three filed lawsuits. Zarda and Stephens both died before the high court ruled.

The cases ended up at the Supreme Court after federal appeals courts delivered conflicting rulings. In Bostock's case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit said Title VII doesn't extend to sexual orientation discrimination. In Zarda's, the Second Circuit said it does. In Stephens's, the Sixth Circuit said Title VII covers gender identity discrimination.

Catholic basilica in Philadephia

Brian Logan Photography/Shutterstock

This was another case on the right to discriminate against LGBTQ+ people. The court ruled unanimously in favor of a Pennsylvania Catholic foster care service's right to refuse to certify same-sex married couples or unmarried couples regardless of their sexual orientation, even when working under contract with the city of Philadelphia.

Roberts wrote in the decision that "other foster agencies in Philadelphia will certify same-sex couples, and no same-sex couple has sought certification" from the foster care service.

The city of Philadelphia had argued that the refusal of Catholic Social Services to certify same-sex couples went against a nondiscrimination provision in the city's contract and also went against the city's Fair Practices Ordinance.

Catholic Social Services and several foster parents sued to claim the actions by the city violated their First Amendment right to free speech. They lost at the trial and appeals court levels,

The court held that the nondiscrimination provision isn't applicable because of an exception allowance in the contract. The ruling does not create a general right to discriminate, LGBTQ+ advocates pointed out, because it turns solely on the specifics of the Philadelphia contract.

However, the court also found, "Under the circumstances here, the City does not have a compelling interest in refusing to contract with CSS. CSS seeks only an accommodation that will allow it to continue serving the children of Philadelphia in a manner consistent with its religious beliefs; it does not seek to impose those beliefs on anyone else."

The ruling didn't mean same-sex couples or LGBTQ+ individuals can't become foster parents in Philadelphia; the city contracts with other agencies that don't discriminate. One, Bethany Christian Services, even revoked its anti-LGBTQ+ policy so it could continue to work for the city. It also didn't mean governments elsewhere can't make contractors comply with antidiscrimination laws, as long as the contract doesn't include an exception clause like Philadelphia's.

Some conservatives, however, wished for a broader right to discriminate. "Today's decision will be of no help in other cases involving the exclusion of faith-based foster care and adoption agencies unless by some chance the relevant laws contain the same glitch as the Philadelphia contractual provision on which the majority's decision hangs," Alito wrote. "The decision will be even less significant in all the other important religious liberty cases that are bubbling up."

Wikimedia Commons

In this ruling, the Supreme Court did what many considered unthinkable, overturning Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that recognized abortion as a constitutional right.

This did not mean abortion will be outlawed nationwide, but it does mean any state can choose to ban it. Since the ruling, about half the states have banned or severely restricted abortion.

The 6-3 ruling came in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which involved a Mississippi law that bans most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. The court heard the case in December 2021, and a draft opinion, written by Alito, was leaked to the press in May 2022.

The final opinion was also written by Alito. He was joined by Thomas, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Roberts, and new Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a Trump appointee who succeeded liberal lion Ginsburg after her death. Sotomayor, Kagan, and Breyer dissented.

"The Constitution does not confer a right to abortion; Roe and Casey are overruled; and the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives," the ruling reads.The decision is relevant to LGBTQ+ Americans because not only do queer people sometimes seek abortions but also because it threatens other rights to bodily autonomy. Alito and Thomas had already expressed a desire to overturn Obergefell, the marriage equality ruling, and Thomas wrote a concurring opinion saying the court should revisit and overrule decisions that struck down state restrictions on contraception, private consensual sex, and same-sex marriage, saying they are "demonstrably erroneous."

Lorie Smith

Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

This was another case that involved the right to discriminate. Denver-area website designer Lorie Smith, owner of 303 Creative, wanted to expand her wedding business but sais serving same-sex couples would violate her conservative Christian beliefs and her free speech rights. She had not been approached by any same-sex couple, but she wanted to preemptively state she would not design wedding websites for them. She sought to include a statement on her website that she will not serve same-sex couples.

She filed suit in 2016 challenging Colorado's LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination law. She lost at the federal district court and appeals court levels. The Supreme Court agreed in February 2022 to hear her case but only on the free speech claim. It heard oral arguments in December 2022. She was represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom, a notoriously anti-LGBTQ+ legal nonprofit.

In 2023, the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority thanks to Trump's appointments, ruled 6-3 that "the First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagrees." All conservatives joined in the opinion, with all three liberals dissenting — Kagan, Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson, who President Biden nominated to the court to replace Breyer when he retired.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion, "Like many States, Colorado has a law forbidding businesses from engaging in discrimination when they sell goods and services to the public. Laws along these lines have done much to secure the civil rights of all Americans. But in this particular case Colorado does not just seek to ensure the sale of goods or services on equal terms. It seeks to use its law to compel an individual to create speech she does not believe."

In the dissenting opinion, Sotomayor wrote, "Today, the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class."

She also wrote, "A business open to the public seeks to deny gay and lesbian customers the full and equal enjoyment of its services based on the owner’s religious belief that same-sex marriages are ‘false’. The business argues, and a majority of the Court agrees, that because the business offers services that are customized and expressive, the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment shields the business from a generally applicable law that prohibits discrimination in the sale of publicly available goods and services. That is wrong. Profoundly wrong. ... Our Constitution contains no right to refuse service to a disfavored group. I dissent.”