We're 15

minutes out from the start of The Ellen DeGeneres

Show, and the studio audience is already on its feet

and dancing. Practically speaking, we don't have a

choice: Nobody could resist the beat of the vintage

funk music pounding through the warm

blond-wood-and-aqua set. Besides, it's fun. Other

live shows push their audiences to compete

aggressively for souvenirs, but here, in NBC's

Studio 11 in Burbank, Calif., guests are told they'll

get an "I danced with Ellen" T-shirt not for having

danced best but for having the best time while

dancing. By the time DeGeneres bounds onto the set

in slacks, blazer, and running shoes, she's the

last to arrive at her own party.

And are they ever thrilled to see her. Their

roar of affection fascinates particularly because

there's no way this far-flung crowd is all

gay-friendly all the time. Yet confronted with one of

America's most famous lesbians ever, everybody

greets her as one of their own.

At 46, DeGeneres is living proof that you can

actually come to the end of coming out. More than

perhaps any other public figure, she has run the whole

gauntlet--professional setbacks; her own public

growing pains; the humiliation of being written off by

colleagues, pundits, and a lot of lesbians and gays as

well. Now DeGeneres is on the other side. Honors and

endorsements are rolling in. She's slated to speak at

one of Harvard Law School's commencement events

in 2005. She's featured in a new global ad

campaign for American Express alongside other highly

individual stars like Robert De Niro, Tiger Woods, and

surfer Laird Hamilton.

More than all that, in terms of her own talent,

DeGeneres is apparently just getting warmed up. After

decades of success in sitcoms, it turns out

she's equally gifted at hosting a cavalcade of

celebrities and coming up with offbeat ways to let

them shine. A good example: When the famously

foulmouthed Colin Farrell did the show, every curse word was

drowned in the studio by the sound of a mighty

ka-CHING. Farrell and DeGeneres had agreed that

he'd be fined $100 per profanity, with the take

to go to charity. The shtick worked brilliantly, granting

Farrell his edge but softening it too. Just as clever was a

good-humored sketch in which Farrell and Ellen fell

into a passionate kiss backstage and he sobbed

brokenheartedly once she was gone. The audience, feeling in

on the joke, loved it.

With this show, DeGeneres has found the

Goldilocks zone: not too sweet, not too sharp, but

just right. Of course, finding that zone keeps her on

a day-in, day-out treadmill she describes as "insane."

"Ellen's running a

marathon," acknowledges photographer Alexandra

Hedison, DeGeneres's partner of nearly four years.

How does that marathon unfold each day? The

Advocate asked Hedison to give us an idea by

shooting one day in the life of her significant other.

What follows is a rare personal glimpse of the woman whose

comedy was one of the few things to unite Americans in

2004. This year we all danced with Ellen. In case you

didn't notice, she led.

Did you always know your show would be such a

smashing success?

No. I thought I'd be good at it. I

didn't know how hard daytime was; I

didn't realize how competitive it was, that

there's a pecking order, until you establish yourself

and your ratings are at a certain point, that a guest

has to go on this show first, then that show,

then that show--all these different games that

people play of "You can't have this person

until they appear on this show," and that kind

of sucks. I didn't realize the amount of

content that you have to come up with every single

day. I mean, we've done, like, 140 shows.

That's incredible.

I know. It's 140 monologues, 140 days walking out

and having something to talk about, 140 times that

I've had to stay completely present with

somebody and not drift off no matter how tired I am.

It's really an intense amount of energy to expend

every day. I'm finding ways of keeping that

energy level up, because it's really hard. But

I'm pleasantly surprised. And now it feels like

there's very little that could really happen that

could hurt us. We're in good shape now.

So you've come up a lot in the guest pecking

order, I'm sure.

Yeah, but...it doesn't matter to me; I

don't care if I'm having them after

every single person or that they've been on

everything. I know I'm gonna do something different

with them. And that's the whole point of the

show, so that people who are watching will go,

"I've seen them on every interview, but

I know when they're on Ellen's show,

I'm going to see something different than I

would see on anywhere else."

Who's helping you come up with the

monologues every day?

I have writers. And I come in--sometimes I have

something to say, sometimes I've given them

ideas. I'll just come in some days--like

today I'm talking about relaxing and different ways

that you can relax--I told them last week,

"Come up with a monologue for that."

Yesterday I had no idea what I was talking about.

[Anne laughs] Oh, public speaking.

I make sure that they have something every

single day, and then they come in and we either write

it together--we just pitch ideas or

they've written it after we've pitched ideas,

and then I rewrite it with them. It's a collaboration.

Do you get any time to yourself?

During the day? No. Literally from the moment I get

here, there are probably 30 things I talk to Craig, my

assistant, about--making decisions. I had radio

interviews this morning when I first came in, then the

writers come in, and then the segment producers come in and

we go over the questions for the guests of the day,

and I rewrite things that I don't think I want

to talk about and change things. Then I usually have

an interview--something like this--and then I go

down and rehearse, then we rewrite things, then I get

hair and makeup. I've never had so much power

over a show. I mean, I guess I did with my sitcoms,

but I didn't care about it. I was like, "I

don't care about the set; I don't care about

the color of the walls." But I make every

single decision on this show. I have executive

producers, but it comes down to coming up to me and saying,

"Here's the option: We do this or we do

this." It's probably 70 to 100 decisions

a day. Every day.

That's grueling.

It's insane. And then it starts over the next

day. I've never been so involved in every

aspect. We just got back from New York--we went

to New York to do that RSVP Suite. I did something

with Donald Trump, I did something for American Express, I

did the Today show. I did something every day

from 6 a.m. until about 8 o'clock at night for

four days. And then I got on a plane and came back and

started yesterday.

Can you ever have a sick day?

No. Last year I got sick--you get sick a lot on

this show, because you're shaking a lot of

hands and there's a lot of contact--and I

talk about everything that's going on with me;

I never try to pretend like something isn't going on.

[Last year] I walked out and I would say,

"I'm sick," and I would talk

about being sick and the cold medicine and how it makes you

feel. You can just feel the audience kind of [makes

a downward gesture]...They don't

want me to be sick. If I'm down, they're

down. So even if I'm sick, I gotta be up,

because it's up to me to keep that energy going.

What a great year you've had--that was

going to be the whole subject, and then the election

happened. Were you surprised by all that?

I feel like things sometimes have to swing a certain way

in order to swing back. You know, everybody has gone

through this. Every group of people that has been

discriminated has gone against these times, and

it'll be fine. You can't think anything else,

or else you're doomed.

I do believe that things will swing back and

that even conservative people will think this has gone

too far now. All I can think about is what I do, which

is make people happy and forget about all that stuff.

Then people that do that for a living--activists and

politicians--are gonna keep fighting, and I can keep

being a representative of what is supposedly not

normal and try to remind people that we are

normal.

We're both from the heart of the red states,

where gay marriage was such an election issue. So many

gay people had their families, in effect, vote

against them. Would you have anything to say to

families like that?

[Pauses] I think in a way, they're

not really clearly understanding that it's a

big deal. I think they're trying to protect

[against] something that they fear. I think anybody

who is going to that length, to vote on some kind of

measure to exclude rights from people, is acting out of

fear. I don't know that I'm the

person--or anybody--who is going to be

able to [change anyone's mind]. I think it's a

matter of realizing that it's just about having equal

rights. It's not about having special rights,

it's about equal rights.

Is getting married important to you?

No. I've never had that desire to stand

in front of a bunch of people and say, "This is

how I feel--everybody needs to know

this." I feel, if something happens to me, that Alex

would be protected financially. We've gone to

lengths where we've had to pay an attorney

money that married people don't have to, to come

in and set up certain rights so that if I'm in the

hospital, she has the right to be in there and make

decisions for me. But not everybody can afford to go

to that length.

I've heard you say in interviews that,

because you're seen as such a hero, people get

reverent with you. That could be a drag sometimes.

You know, I was talking about this with Alex the other

day. I guess it's just hard for me to

understand because it's my life and it's

just who I am, but I understand the impact that it's

had on other people. I have to appreciate that, and I

shouldn't push it aside.

That's why when people applaud when I

walk out there, as much as I know people at home are

going, "That's

enough--we're at home, we don't need to

hear the applause that long," if people feel

like whooing, I'm gonna let 'em whoo.

[Anne laughs] How often in a day do you

feel like whooing? I want people to feel how they feel. What

I don't want people to feel is less than.

In 2000, I was in the audience at the Concert for

Equality in Washington, D.C., when you got the longest

standing ovation I've ever heard.

You'd had such a difficult year. But then

came that unbelievable ovation. What was that like from

your end?

It was wild. It was wild.

Does that ever come back to you in your mind?

No, not until you just said that. I try not to

hold on. I don't know if I try not to; I just

don't hold on to stuff. Things happen, and

it's all part of this puzzle that keeps making me,

and I try to figure out who I am by all these little

pieces. That was definitely a moment that was just so

emotional. It was pretty cool.

I want to ask about this genius you have: When

somebody says something, you instantly know what to say

back. It's not quick; it's instant.

Do you see that comeback in your mind? Is there a

sensation that comes to you?

There's a sensation after it comes out of

my mouth, like, Oh, that was good. [Anne

laughs] I mean, seriously, that's not any

controlled...it's not me.

Everybody's born with different talents: somebody who

can dance really well or play sports really

well--that perfect basketball shot where

there's just all net...

That sweet spot.

Yes, and that's how I feel. If you know what

hitting that sweet spot feels like when you hit a golf

ball, that's what it feels like when something

comes out of my mouth that fast. Sometimes I think of

something when somebody's talking and it takes me a

few seconds, and by that time they're starting

to talk about something else and I have to let it go.

And I'm so mad at myself, because had I been

two seconds earlier, I would've had a great response.

But it's more important to let the person talk,

because it's not about me, it's about

showing them in their best light.

And some days I'm quicker than others.

It's like anybody, whatever you do: There are

days that I'm fast, and there are days where

I'm really, really funny, and then there are days

where I'm not funny. I don't try to be

funny when I'm not funny, because I think

that's really annoying.

That's smart.

It's just, people that are on all the

time--and I know people that are really funny

people--after a while, when it doesn't

ever turn off, it's like anything. You're

like, "OK, that's... [mimes

fatigue] funny." You just can't

laugh after a while. Sometimes I get people trying

harder to be funny around me too, to show me that

they're funny so that I'll somehow bond

with them. And that's hard, 'cause you

can feel when somebody's trying, you can feel when

it's forced.

The things you can say as a stand-up in a club are

very different than what you can say on your show. Are

you eventually going to write a book including

everything you would've said on the show

but couldn't because it was daytime, because it

was nice?

No, this is really my humor, this is really who

I am. I'm not censoring myself. I think

that's the misconception with me--and

that was the problem with me getting the show in daytime.

"She's gonna have to be different,

'cause it's daytime." If I had a

nighttime slot, I would have the same exact show that

I have right now.

If I do have a thought of something that would

be kind of off-color, it's really just like

those inside thoughts that anybody would have. When

those things happen, I don't say anything, and then

the audience laughs with me--everybody's

thinking the same thing.

Yesterday, Ashley Judd was on, and I said,

"Is your husband here?" She said,

"He's shopping today--here I am

working, and he's shopping. We're big into

role reversal in our marriage." I was like,

"Please tell us about that." Because

you're not going to ignore the fact that she's

talking about role reversal in their marriage. Then it just

was a laugh and we went on.

Elton John was on with you on Monday. Do you two

ever play off the fact that you're both famous

gay people?

No. I don't live my life

like...I'm not even aware that I'm

famous until people remind me. I wake up every single day

and I have my life, and it's pretty normal. I

drive myself to work, I don't get driven to

work; I don't have a chef that makes me

breakfast in the morning. I don't think that

I'm famous until I come here and it's

like, Oh, that's right. Even then, this

is my job.

And I don't think, I'm going

home to my girlfriend and I'm gay.

That's my life, that's who I love, my

girlfriend and I are in love, but I don't think,

I'm going home to my gay girlfriend.

And I don't think, Oh, that's right,

Elton's gay and I'm gay and we're

together. To me, that is a problem, when there is too

much emphasis. Also, it's not making steps

forward. It's continuing to say "us and

them." And I don't think it is "us and them."

Well, it doesn't make sense.

There was a time when people were saying I was not gay

enough, that I wasn't doing enough and I

wasn't an activist, and then straight people

were saying, "She's too gay." Any time

you start pointing the finger and judging somebody else,

then you have no right to get mad at them for judging

you, because they feel just as strongly as you feel.

It may not feel good to you, but they have that right.

A lot of us think of you as--I hate the term

role model--as our visible person, I guess. You

went through the fire of coming out in front of

the world. And now you're at the place

where so many of us would like to be. Everybody knows

it's you and Alex; they know you're

gay. But it's not the first thing they

think of. Have you outlasted your own coming out? Are

you past the worst of it?

Oh, yeah. I mean, the worst of it really was--I

don't feel like [my past relationship] needs to

be mentioned in every single thing that I do, but

unfortunately, that is what contributed to this whole

thing. And it is one of those pieces that was necessary to

me--a huge amount of growth. Huge. I'm

grateful for that relationship, I'm grateful

for all of it, because I look at that and I go,

What made me that person that allowed all that to

happen? It's hard to say what caused the

fire that I went through, as you say. But whatever it

was, it was all good and all necessary, because

it's even sweeter where I am now.

I believe you.

I worked really, really hard for my career up until that

point. I made a decision to come out because it was

the right thing for my soul, for me as a person, and I

realized that it was more important to fully embrace

and not to feel one ounce of shame about myself. Up until

you make that decision, you can tell yourself all you

want that it's nobody's business and it

has nothing to do with anything--[but] it has

everything to do with everything. Once you embrace it,

then it's got nothing to do with anything.

It's so hard to see until you're

through it.

It's huge, huge...like you're

carrying around a piano on your back and you

don't even know it until you say, "Wow,

this is who I am and I'm not gonna hide it anymore

and I'm not gonna feel shame about it and

I'm not gonna worry if people hate me or think

I'm a freak or think I'm gonna lose my

career." It's so much stuff you're

carrying around attached to that one tiny thing. And

then once you do it-- [Smiles]

For me, when people go, "Do you hide the

fact that you're gay on the show?" or

"Do you worry about that?" I

don't even think about that. But I used to think

about it all the time, because I was making sure that

Ooh, if I say this, will they know that

I'm gay? What if I do this? What if I slightly

look at a girl? You can't possibly be

the best person you are at whatever it is, because

you're hiding.

You're a little perpetual self-checking

machine, and that's all you are.

Now it's got nothing to do with anything. I allow

anything to be said [and don't worry about]

anything that I say, because I'm not scared of

anything anymore.

Let's talk about Oh, God! which

you're planning to remake in 2005 with yourself

as God. Your comedy has touched on God before. In

fact, the routine that got you started was called

"Phone Call to God." But I'd have

thought that if you were going to remake this

film, you'd have put yourself in the John

Denver role.

Why's that?

Because that seems to be your comedy persona. Not

the person who's in charge, but the person

who's tentative, who's feeling her way.

That's what's going to be different about

this movie. We assume that God is completely in

control of everything. That's a really easy way

to not take responsibility, to go, "Well, God wants

it this way" and "God planned it this

way." How do we know that? Maybe God's

going, "Oh, that's not what I meant."

I get it. That's interesting.

If we're created in God's image and

likeness, supposedly, then there are mistakes;

there's humor. We're still writing [the

film] right now. It may leave you questioning, "Do

things happen for a reason? Are things all planned

out? Or are things all up to us, and we do with them

what we will?"

What do you think?

We make our choices, because--I think everybody

can relate to this--no matter how many times you

keep being somehow herded [away from] one direction,

you just ignore it and keep going back to that

direction, whether it's a bad relationship or the

same kind of person that screws you over every single

time and you think, It's gonna be different

this time.

So the question is--

If there's something that is the higher

intelligence, the higher power, why would something

that powerful and that intelligent not give us that

same intelligence? Why would something with that

intelligence say, "I'm gonna be just a little

bit smarter because I have ego"? That's

what we would do. So why wouldn't

something that's all love and all giving not give

equally to everybody?

God, obviously, is a hot topic in America right

now. Do you think some people might prefer not to see

God played by someone who's gay?

Oh, I'm sure that when George Burns did it, they

were upset that a Jewish man was playing God. That was

a problem. But, listen, I'm not making The

Passion of the Christ, I'm not making a

political movie, I'm making a comedy. Warner Bros. is

full steam ahead--we're making the movie.

If it gets some people upset, they should come see the

movie and see what they're upset about before

[judging], because it's insane. I also played a fish,

and I wasn't a fish.

True.

There will be things said [in the film] that I believe

in, because it's what I do, even though my

comedy is not political. When I do "Phone Call

to God," or when I go to God's house to

visit [in 2003's Here and Now], I always slip

something in there that I care about. When I was doing

the visit to God and saying, "I'm sorry

that we're chopping the trees down, I'm

sorry we're killing each other, I'm sorry we

call each other names," there's always a

punch line at the end of it. When I ask God what the

hardest thing about being God is, and God says,

"Trusting people--you never know if people

really like you, or if it's just 'cause

you're God." That's true.

You've had a lot of experience with that,

haven't you?

Yeah. Right. So wouldn't God have the same

problem? It's a comedy, yet it's all

stuff that, I hope, will make you think.

In "Phone Call to God," you asked

God, "Why are there fleas?" Have you

figured that out yet?

[In "Phone Call"] God says, "There

are people employed by the flea- collar

industry," which is true. [Pause] And the

sprays. [Anne laughs]

But that's why the environment is so

important. You take one thing away, and something else

isn't eating. And if that isn't eating,

then something else isn't eating. And it all ends up

with us. We're all part of this huge ecosystem,

and we all need every single thing here. It's

not like we can possibly go, "Well, we

don't need that anymore." We do. It's

all imbalanced because we're making it

imbalanced. Fleas are as important as the gorilla or

the horse or the fish or everything else that we're destroying.

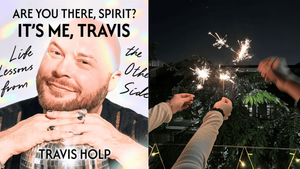

In this photo essay, what do you think people are

going to be surprised to find out about your daily life

when they see these pictures?

How boring it is. They'll be like, "Oh,

man, this is a disappointment--I want my money

back!"

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes