Mitt Romney is

the target, abortion is the issue, and the $100,000 ad buy

will change the tone of the Iowa and New Hampshire

presidential primaries.

This weekend

marks the first negative TV advertising in the two early

voting states as campaigns headed into the critical weeks

before the first vote, with an independent group's

claim that the former Massachusetts governor has

flip-flopped -- a sometimes crippling charge in

presidential politics. Analysts say similar negative ads are

likely to air against Romney's chief GOP rival,

Rudy Giuliani, whose positions on gun control and

immigration are markedly different from those he

espoused as New York City mayor.

The anti-Romney

ad campaign, by a Republican group that supports abortion

rights, is fairly modest in scope. But it may open the door

to bigger ad buys targeting other candidates and

topics, several campaign veterans said.

''This will be

the beginning of it,'' said Patrick Griffin, a

Manchester-based advertising executive who handled President

Bush's 2000 media effort in New Hampshire.

Given the pending

ad against Romney and the confrontational tenor of

Wednesday's Republican debate in Florida, Griffin said, the

top campaigns must be ready to launch hard-hitting ads

the instant they decide the benefits outweigh the

risks. ''You can be sure there are scripts written

and, very likely, spots produced,'' he said.

And if not on

television, then on radio. Log Cabin Republicans on

Thursday launched a 60-second anti-Romney radio ad

criticizing his tax record.

Negative ads are

certainly possible in the Democratic contest as well.

But strategists say they are not surprised to see them first

in the Republican race, where front-runners Romney and

Giuliani have left a long evidentiary trail of their

changed positions on key issues.

''It's a

target-rich environment for negative ads,'' said Dante

Scala, a political scientist at the University of New

Hampshire.

Accusations of

flip-flopping have animated campaigns for years. They

proved especially damaging to Democratic presidential

nominee John Kerry in 2004, and they have dogged

Romney and Giuliani this year.

Thus far the

accusations have arisen only in debates and news accounts,

not in potentially powerful TV ads that often employ ominous

music and grainy black-and-white or slow-motion

images. And while campaign ads have saturated the Iowa

and New Hampshire airwaves for weeks, they have been

mostly upbeat biographical spots.

That will change

this weekend when the group Republican Majority for

Choice starts its ads -- in Iowa and New Hampshire

newspapers and TV spots -- calling Romney a

flip-flopper on abortion.

The ads'

potential impact is unclear. Romney repeatedly has

acknowledged he was an outspoken supporter of

abortion rights until he changed his mind a few years

ago.

''I don't know

how many times I can tell it: I was wrong,'' he said in

Wednesday's debate. Voters seeking candidates who are ''not

willing to admit they're ever wrong,'' he said, will

''have to find somebody else.''

The major threat

to Romney would be TV ads suggesting his conversion was

politically motivated to appeal to Republican primary

voters. Among the rivals already raising the issue is

U.S. senator John McCain, who has said Romney's

biggest challenge ''will be convincing Republicans he

has principled positions on important issues.''

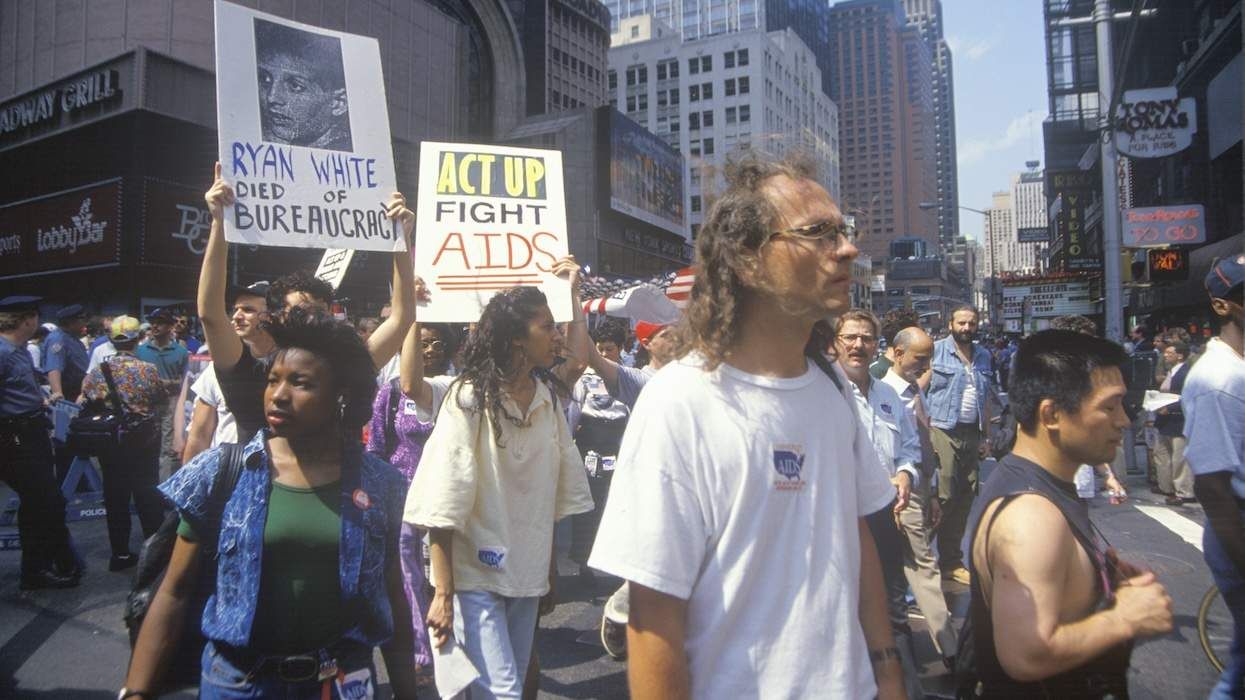

Questions about

gay rights also might provide grist for anti-Romney ads.

When he unsuccessfully challenged Edward M. Kennedy's Senate

seat in 1994, Romney vowed to outdo the senator in

championing the rights of gay men and lesbians in the

workplace. ''We must make equality for gays and

lesbians a mainstream concern,'' Romney said at the time.

He never

supported same-sex marriage, and he now highlights his

support of ''the traditional family'' and a

Constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage.

Some Republicans

feel Giuliani is equally vulnerable to charges of

flip-flopping if a televised feud begins.

As mayor of New

York City, Giuliani sued gun makers and distributors,

backed a federal assault-weapons ban, and once described the

National Rifle Association as extremist. He says he no

longer holds those views because the terrorist

attacks of 2001 changed his thinking about weapons and

personal protection. He was quoted in 2002 and 2004,

however, still staunchly supporting gun control.

Giuliani promises

to crack down on illegal immigration, a message also at

odds with his record as mayor. In 1996 he said there are

times ''when undocumented aliens must have a

substantial degree of protection'' to feel safe

sending their children to school, reporting crimes, and

seeking medical treatment.

Such policy

shifts by Giuliani and Romney are ready-made for negative

ads, campaign strategists say, but the strategy carries

risks. New Hampshire's all-important independent

voters are especially leery of one-sided claims, and

''there's a danger it can backfire,'' said Dean

Spiliotes, who writes a nonpartisan political blog in New

Hampshire.

Moreover, several

analysts said, a serious Romney-Giuliani spat could

catapult another candidate, such as McCain, to the top.

For all those

reasons, it is possible that most or all of the early

negative ads will be aired by independent groups, such as

the one now targeting Romney on abortion. If the

candidates decide to launch their own attack ads, ''I

think it's likely to happen in the last week or two,''

said Andy Smith, a pollster at the University of New

Hampshire.

Meanwhile,

candidates will anxiously monitor polls, campaign event

crowds, and other signs that their campaign is going up,

down, or nowhere. Ultimately, at least one candidate

will decide that negative ads are worth the risk, said

Michael P. Dennehy, McCain's New Hampshire-based

national political director.

''No candidate

wants to be the first to go negative,'' Dennehy said in an

interview. ''But it will be done, mark my word. It's just a

question of when.'' (Charles Babington, AP)

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes