Why John Amaechi didn't change the world of professional sports.

December 14 2007 12:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Why John Amaechi didn't change the world of professional sports.

To many gays and lesbians who care about sports, this coming-out was (literally) the big one -- the one that would officially open up the idea of homosexuality to a particular culture that has been anything but embracing.

For eons, participants in professional athletics had treated gays and lesbians not as people but slurs. Play soft and you're a faggot. Dress colorfully and you're queer. Step into the shower with a slightly effeminate teammate and you should make sure to grab soap on a rope.

Why, it wasn't all that long ago that one of my former Sports Illustrated colleagues walked through the locker room of the NBA's New Jersey Nets after a game while wearing (gasp!) a yellow scarf. The nerve! "Ho-mo-sex-u-al!" chanted David Benoit, an eminently forgettable forward. "Ho-mo-sex-u-al!"

The joint broke out in snickers.

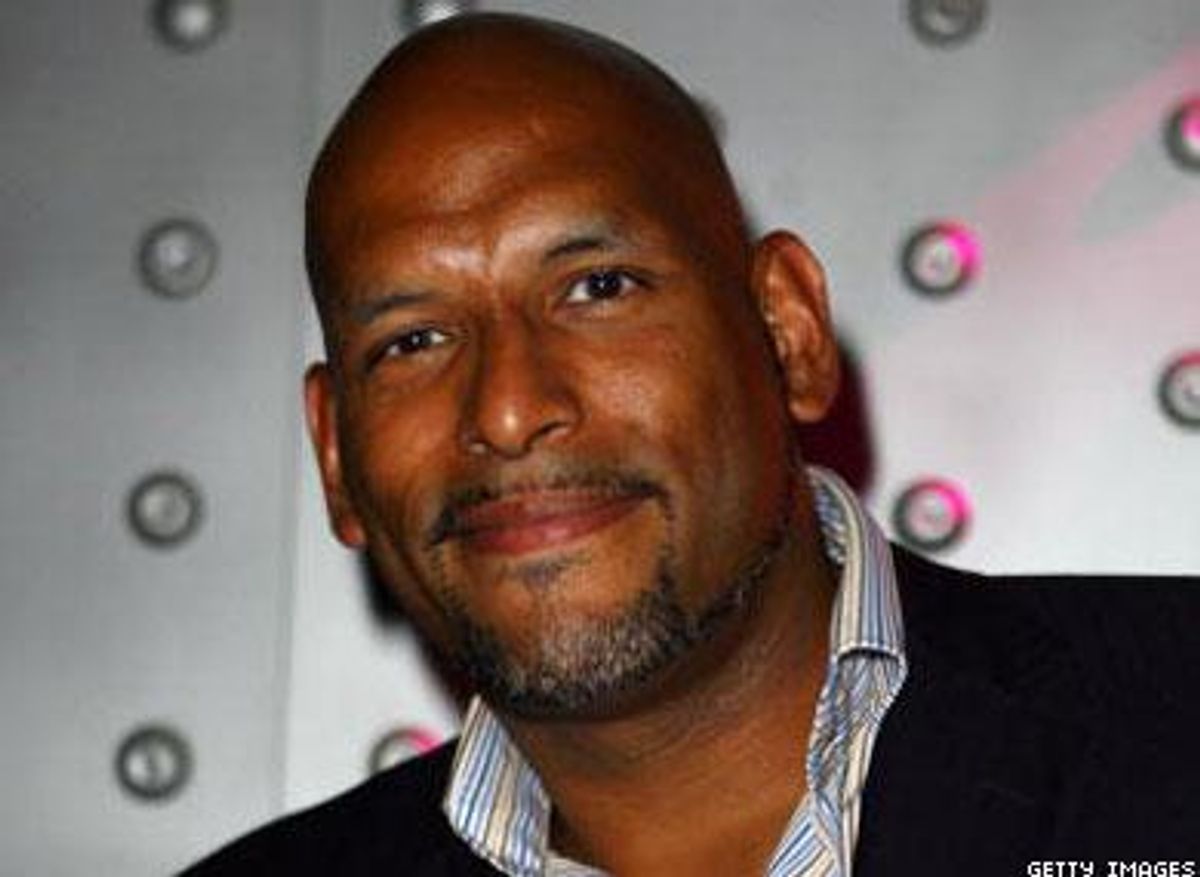

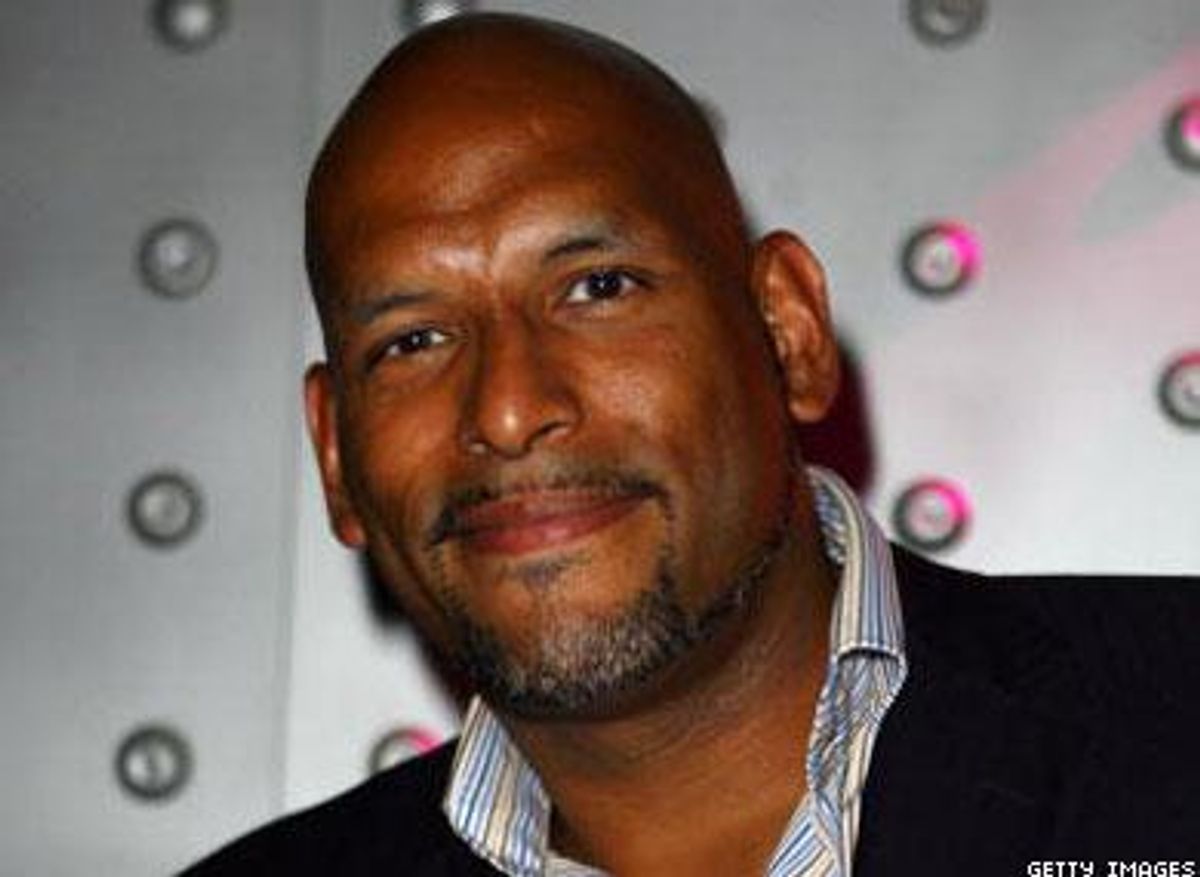

But in February 2007 the tide was surely about to turn. A former NBA center named John Amaechi appeared on ESPN's Outside the Lines to speak publicly about his life as a closeted professional athlete. No, Amaechi wasn't the first retired jock to come out. But he was easily the most recognizable: Not only was Amaechi a 6-foot-10, 270-pound mountain of a man, but he had spent his career battling head-to-head against the Shaquille O'Neals and Patrick Ewings and Tim Duncans of the league -- without headgear to make him anonymous.

Though courageous men like Dave Kopay, Glenn Burke, Billy Bean, and Esera Tuaolo undeniably stand as trailblazers in the battle for gays to gain acceptance in professional sports, they also could walk down any American street without being noticed. Amaechi cannot. His size alone gives him away.

So when Amaechi appeared on Outside the Lines, then shortly thereafter released his autobiography, Man in the Middle, it was hard not to think this would finally serve as a gateway toward acceptance and equality. Amaechi had been retired for just three years. About half of the NBA's players had competed against him--known him as a peer, embraced him as a professional, and admired his feathery touch around the rim. Surely their minds would be opened by John Amaechi, gay man. Surely they would understand and accept.

Surely...

Sigh.

Over this past year, when American attitudes about gays have seemed to shift dramatically in areas ranging from arts to politics to education, it is a sad, harsh truth that within pro sports Amaechi's actions accomplished absolutely, positively, 100%...nothing.

Oh, there were two or three players who spoke on Amaechi's behalf, who expressed hope that more gay men would feel comfortable being their true selves. Said Grant Hill, now of the Phoenix Suns: "The fact that John has done this, maybe it will give others the comfort or confidence to come out as well, whether they are playing or retiring."

Hill's words, however, were drowned out by a tidal wave of bigotry. Famously, there was the rant of Tim Hardaway, the retired All-Star guard who told a radio host, "If [Amaechi] was on my team, I would really distance myself from him because I don't think that's right, and I don't think that he should be in the locker room while we're in the locker room." Worse, however, was the response of active players, the men charged with opening their hearts -- and dressing quarters--to a gay peer.

Philadelphia forward Shavlik Randolph warned of being exposed to "gayness," while teammate Steven Hunter allowed that he'd play with a homosexual "as long as he [didn't] make any advances toward me." (Good news, Stevie: We've seen your picture -- you've got nothing to worry about.)

The most disheartening reaction came from Cleveland's LeBron James, the new face of the league, Michael Jordan's heir apparent. Had the so-called King James expressed support for Amaechi, it would have been the verbal equivalent of Brooklyn Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese placing his arm around Jackie Robinson during a 1947 road trip to Cincinnati -- a blatant signal to peers and fans that the outsider deserves respect. That gesture was so impactful that it is now depicted in a bronze sculpture outside of KeySpan Park, Brooklyn, N.Y.'s baseball stadium.

James was given the opportunity to make an equally profound declaration: to say bigotry had no place in his league. Instead, James's words rang familiar. "With teammates you have to be trustworthy, and if you're gay and you're not admitting that you are, then you are not trustworthy," he said. "So that's like the number 1 thing as teammates--we all trust each other. It's a trust factor, honestly. A big trust factor."

Pathetic.

What has prevented the NBA and other male professional leagues from warming up to homosexuality isn't so much a steadfast bigotry as it is a mind-numbing ignorance and disinterest concerning all things progressive. To reach the highest level of American athletics, players must devote nearly all their time, energy, and passion to a pursuit that has literally nothing to do with social enlightenment. James, for example, seemingly can leap as high as an oak tree and dunk blindfolded over a 15-foot barbed wire fence. Ask him to explain why he feels comfortable driving an 8-mile-per-gallon Hummer (his vehicle of choice) in these days of global warming and alternative fuels, however, and he'll stare blankly off into the distance.

Indeed, there's a reason why the majority of professional athletes either don't vote or are registered Republicans; drive gas-guzzling, smog-producing vehicles; and struggle to maintain their fortunes. They're trained to "catch ball, throw ball" -- not ponder issues with any sort of depth or analysis.

Hence, those of us anxiously anticipating the first openly gay male athlete playing on a professional sports team need not hold our breath. In baseball all has been silent since former New York Mets catcher Mike Piazza presided over an embarrassing 2002 press conference to declare "I'm not gay." In football Esera Tuaolo's revelation in the same year was met with NFL-wide silence. As for the National Hockey League, well, unless one wants to suffer nightly dental realignments, he'd best keep his homosexuality to himself. "It won't go over well," says one person close to the league. "You'd get beat up pretty good."

Such is the reality of the athletic world. Bring your game. Don't bring your gayness.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered