As the director

of A Jihad for Love -- the world's first

documentary to take a close look at Islam and homosexuality

-- I am coming out as a Muslim man. My gay identity is

secondary. Queer cinema is filled with stories of gays

and lesbians revealing their sexuality, but my film is

about people revealing their religion. With this film,

the story of a 1,428-year-old religion is told by its most

unlikely storytellers -- gay and lesbian Muslims.

Making this film

and finding subjects who would be willing to share their

stories with me was a "jihad" (struggle) in itself. In many

of the cases it took me years to convince the subjects

to participate, and I had to build relationships of

mutual trust with them. What made it easier and

certainly worth the challenge was that I was a Muslim like

my subjects and we had much in common because of the

backgrounds we came from. The entire process took six

years of my life -- and these six years I cherish

dearly for everything they taught me, not just about my own

Islam but of the universal jihad, or struggle, to belong.

This film tries

to construct the first real and comprehensive image of

these unlikely creatures -- to be P.C., gay, lesbian,

bisexual, transgender, and queer Muslims -- and it is

forcing many audiences to realize that these terms are

a Western construct. Let me be clear: None of these

categories means anything to many of my friends living in

Cairo or Islamabad. If anything, the languages they

speak -- Farsi, Arabic, Urdu, Punjabi, and Bengali --

have very few words of affirmation to describe the

"odd" and "unnatural" behaviors, so to speak, that we

indulge in. The cinematic representation of these complex

identities therefore has come with many of the challenges of

almost developing a new language.

It is a

little-known fact that a sexual revolution of immense

proportions came to the earliest Muslims, some 1,300

years before the West had even "thunk" it. This

promise of equal gender rights and, unlike in the

Bible, the stress on sex as not just reproductive but also

enjoyable within the confines of marriage have all but

been lost in the rhetoric spewing from loudspeakers

perched on masjids (mosques) in Riyadh, Marrakech, and

Islamabad. The same Islam that has for centuries not only

tolerated but also openly celebrated homosexuality is today

used to justify a state-sanctioned program against gay

men in Egypt -- America's "enlightened" friend in the

Middle East.

When in New York

I often wonder how the lives of the subjects in this

film would strike the consciousness of, for example, a

Chelsea boy. Traveling to more than 10 countries with

the film in the last few months has made me wonder

about the absence of religion within "gay" lives.

Clearly, spirituality can provide a kind of freedom. But it

is also clear that for too many of us religion has not

remained an option.

For the last six

years, I have found myself immersed in the souls and

spirits of the people who have shared their lives and their

most private moments with my camera. Sometimes when I

look at the footage of the gay Iranian refugees who

have almost no material or spiritual support or the

gay man who was tortured in an Egyptian prison for two

years, I feel a tremendous disconnect. Growing up in

worlds not very dissimilar to theirs, I know I

understand and can empathize -- but knowing that I sit

in America or in Europe working in the film world, I feel a

sense of tremendous emptiness. This disconnect is

similar to what a filmmaker feels when real

people and real relationships turn into

two-dimensional characters in a movie.

Sometimes in

these worlds, traveling with my American Jewish producer and

others, I feel we could be at the edge of some kind of

revolution within Islam. As a Muslim, I know that this

could be my jihad. But then the disconnects come and

haunt me at night. Yet whenever the gay imam in the

film, Muhsin, or the Egyptian refugee, Mazen, join us, the

dots all seem to connect very well.

For any filmmaker

who sets out to make a work that is intensely personal,

the process is emotionally overwhelming. As a gay Muslim

myself, I had a sense of shared struggle and shared

pain with all of the subjects. While the camera was on

(I was the primary camera operator) there was always an

exchange of emotion between me and them. It was my hope that

our mutual histories, cultures, and struggles would

translate to the screen. I cannot think of another way

of working when you are examining a community where

the silence has been so loud and so overwhelming.

I never sought

government permission in any of the countries where I

filmed because I knew it would not have been granted. What

was always foremost in my mind was the safety of these

beautiful human beings, these devout Muslims whose

lives I was documenting. I took extreme precautions to

make sure that the tapes I shot were always safe. I would

always record "tourist-like" footage at the beginning

and end of a tape, and I would always store the tapes

in my check-in baggage, with a prayer. Security staff

at airports in fundamentalist regimes (the United States

being a good example at this time) are not the friendliest

people. I did have a difficult time in some countries

because filming such profound human stories is hard

for anyone, but at the same time I knew that I was

filming while I was essentially there as a tourist. The

countries that were easiest to film in were Turkey and

of course India, my home country. In both these

nations, which have significant Muslim populations (India

has the second-largest Muslim population in the world, after

Indonesia, and Turkey is 99% Muslim), the attitudes

toward homosexuality are definitely more open than in

others, and people accept the idea that there is a

spectrum of human sexuality.

One personal

challenge in making this film was to keep my deep respect

for and belief in my faith paramount. Sharing some of the

stories of condemnation, of isolation, of pain, would

make it easy to issue a blanket critique of Islam. I

knew that as a Muslim I could not allow myself to fall

into the trap of being an apologist for my faith, joining

the bandwagon of post-9/11 Islamophobes. I knew that I had

to be a defender of the faith as a Muslim filmmaker

and at the same time engage in a critique of what I

knew was wrong in orthodox Islam's condemnation of

homosexuality. I have always said that I made this film with

a Muslim lens, as a Muslim filmmaker who also happens

to be gay. Too many films about Islam right now are

made by Western, non-Muslim filmmakers, which while

commendable is also problematic -- in a world that now

largely perceives Islam as a problematic monolith.

Currently our religion is under attack from within

(from an extremist fringe) and from without (by

governments and media only focusing on the violence). Islam

needs us to step out as Muslim artists and take back

the discussion of our faith.

Our last battles

of acceptance remain to be fought on the front lines of

religion. With our "jihad for love" we bring Islam out of

the closet.

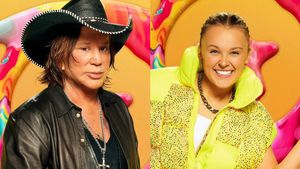

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4