Seeing a

production of a newly commissioned opera like Howard

Shore's The Fly (based on the 1986 David

Croenenberg film, for which Shore also wrote the

music) leads the critic to ask himself the age-old

question: "Just what is opera?" Is it merely a play

set to music? It is that, certainly, but this definition

seems hardly satisfactory. Is it merely a theatrical

entertainment with good tunes? Some operas do fit this

description, but this also seems to miss the mark.

Opera, as an art

form, is a dramatic entertainment in which the music

should enhance the drama, should add to the

dramatic experience in a way that words alone cannot.

And this is not an easy task to undertake, thus the

failure of so many recent attempts at the form. And thus

(sadly) the failure of Shore's new work, just

unveiled by the Los Angeles Opera.

Not that Shore

chose an unviable subject. The original film (and the

short story on which it is based) is bristling (excuse the

pun) with operatic possibilities. For an opera to work

in the theatre, it must contain real dramatic

potential, which The Fly provides

in abundance.

It is also a

subject with which Shore is intimately familiar. Shore was

also provided with an excellent, highly literate, and very

witty libretto (written by David Henry Hwang), a

top-notch cast, superb staging, and a director who

knew the story inside and out (Cronenberg himself). So how

come the opera doesn't (excuse me again, and

I'm sure I'm not the first to say this)

"fly"?

Unfortunately,

the fault must be laid at Shore's feet. As stated

above, the music of any opera (despite whatever kind

of musical language the composer chooses) must bring

out depths within the text, elucidate them, and

transfigure them as only music can. Shore, at least in this

case, just does not deliver.

So many moments

in the drama should have been highlights but never

unfolded in that fashion. The musical textures in the score

are monochrome, lacking any kind of coloring, all

remaining fixed on one tonal level. In fact, it all

sounds like so much background music.

Not that the

opera doesn't have its moments. It's told (as

the 1986 film wasn't) in flashback, from the

viewpoint of reporter Veronica "Ronnie" Quaife

(Ruxandra Donose), in an unspecified period that

appears to be the late 1950s. At a scientific awards

reception, Ronnie meets scientist Seth Brundle (Daniel

Okulitch), who takes her back to his place to see his

... telepods, two giant boxes that look very much like

TV consoles and facilitate the miracle of teleportation.

There's

not enough room here to go into the details of the plot

(those familiar with the film will find most of it

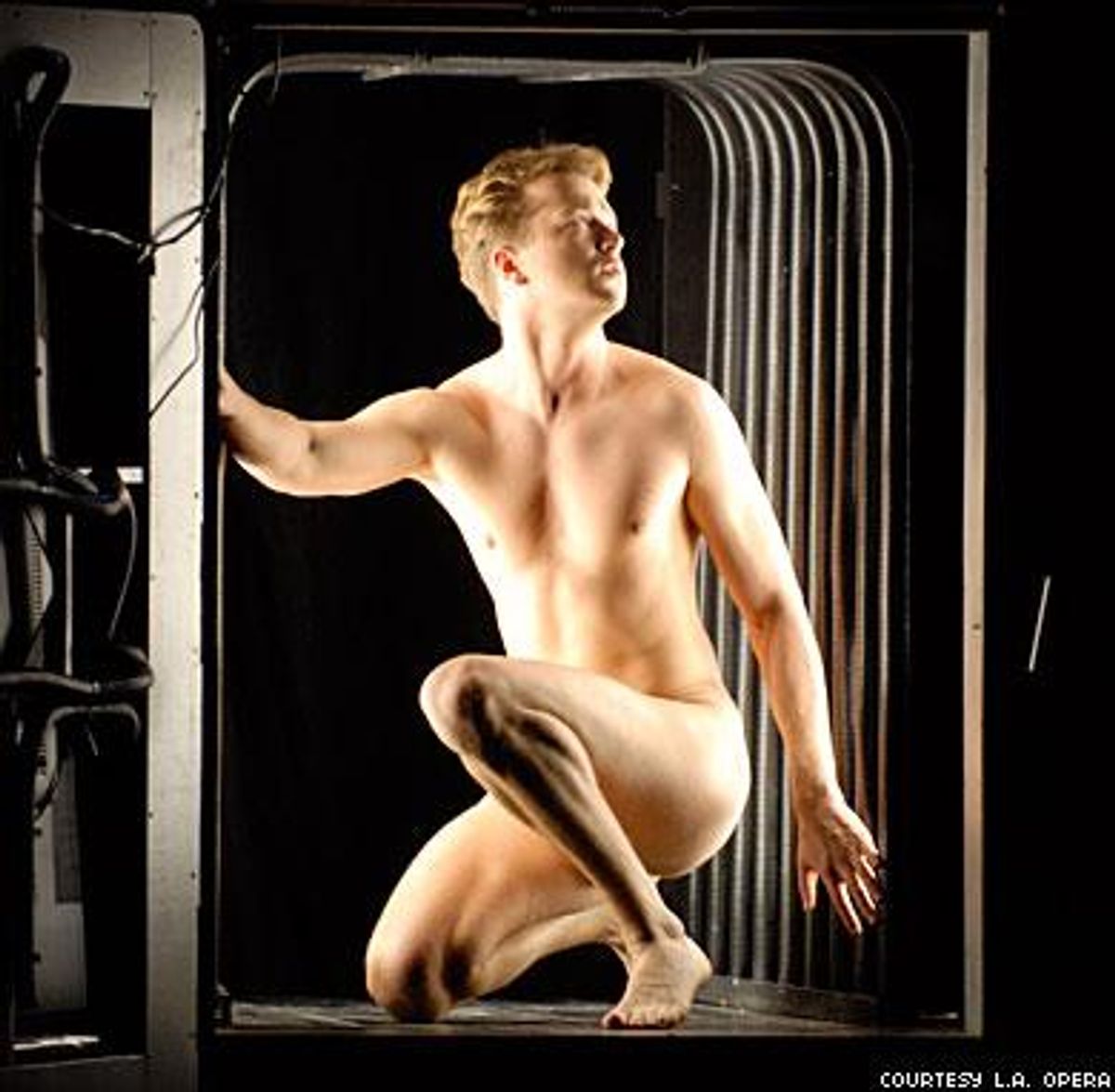

pretty much unchanged). The first act gets off to a

rather slow start, but a love duet between the two

principals is one of the more unexpected oases in the rather

dry makeup of the score, as is the compelling finale

of the act, which includes full-frontal male nudity

(and Okulitch is certainly nice to look at). It is

here that Shore produces the only example of motivic

development in the score: "All Hail the New

Flesh," heard earlier in the act, returns

triumphantly at its end.

The second act

enmeshes us deeper and deeper in an operatic chamber of

horrors, but once again the score never seems to grow; it

just hums along doing its atmospheric best but never

taking the text to the next level. An excellent moment

for an operatic showstopper, a nightmare scene in

which Veronica dreams she is giving birth to a huge larva,

falls flat, and Brundle's ultimate

transformation into a human-fly hybrid, while horrific

to observe, elicits nothing memorable from Shore's

pen.

That being said,

one could not imagine the opera being better presented

than it was at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Cast members

(most of them making their Los Angeles Opera debuts)

are uniformly excellent, especially the two leads.

Okulich's Brundle is everything it should have

been -- masculine, athletic, slightly creepy, yet

sympathetic, as well as being beautifully sung.

Donose's Veronica is acted with passion and

pathos, her rich, creamy soprano caressing each note and

making much out of very little.

Neither can the

production be faulted. Pacing, staging, costuming,

everything smacks of an intense desire to make the best

entertainment possible.

But that draws us

back to our original query -- what is opera?

Ultimately, it is an opera's score, not the sum of

its parts (no matter how superb) that make it a

success, that ensure its immortality. Howard Shore is

undoubtedly a talented musician, perhaps even a great one,

and he is not the first musical talent to have

struggled with the operatic form and lost. What makes

The Fly so tragic is what it could have

been.