On Wednesday,

October 7, 1998, Matthew Shepard was found tied to a fence

on the Wyoming prairie, barely alive, his skull fractured

and his brain stem crushed. Comatose, he was taken

first to a Laramie hospital, then to a better-equipped

one in Fort Collins, Colo., where he died five days

later. We may never know what his killers, Aaron McKinney

and Russell Henderson, intended to do when they first

approached Shepard at Laramie's Fireside

Lounge. We only know that, whatever their intention, they

ended up murdering him.

Almost instantly,

his death became a flash point in this country's

reckoning with gay people, and the cute, clean-cut

21-year-old became a symbol of the ravages of

intolerance. The tragedy sparked vigils around the

world and led to federal hate-crimes legislation that bears

Shepard's name, currently pending in Congress.

(Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama has

promised to sign the bill if elected.)

Shepard's

impact can also be felt in the work of the Matthew Shepard

Foundation, headed by his mother, Judy, whom we spoke with

for the following oral history -- along with friends

and Laramie residents; the police chief who oversaw

the investigation into the murder; and artists

influenced by that tumultuous week.

JUDY SHEPARD When we got the phone call, they talked to my

husband, Dennis. We lived in Saudi Arabia at the time.

They just let him know that Matt was in the hospital

and that his condition was critical.

TIFFANY EDWARDS HUNT, former Laramie

Boomerang reporter I was in the newsroom. I

had the afternoon/night shift, and I heard some things

on the police scanner. They had scrambled it, so I was

trying to understand what kind of code they were

talking. I had a vague idea of where they were because

there's a bike trail out there. I remember

thinking, Oh, I wonder if this is a university hazing.

REVEREND ROGER SCHMIT, then-pastor of St.

Paul's Newman Center in Laramie I got a

phone call from parents of a university student. They lived

very close to where Matthew [was found], and they said

something like, "This is probably going to end

up in your lap: They just found a student really

injured badly. Seems to have been beaten out there at that

fence." Somehow they knew he had a University

of Wyoming student I.D. card. Later I called the

hospital and found out they had already taken him to Fort

Collins.

ROMAINE PATTERSON, Shep-ard's friend; now a

Sirius OutQ show host I was working at a gay

coffee shop in Denver that Matthew had frequented.

[Shepard lived in the city briefly before enrolling at the

University of Wyoming.] One of our regular customers

called and left a message for me to watch the evening

news. He had seen a story that a young man named

Matthew Shepard had been in a fight or something in Wyoming.

The idea that Matt was in an altercation seemed absurd

to me; I thought he must have a broken arm. I watched

the news and called my sister Trish, who lived in

Laramie. She said, "These two guys took this kid out

to the boonies and robbed and beat him really

horribly, and now he's probably going to

die." I said, "I think he might be my

friend."

SHEPARD We didn't have any information. But I was

pretty sure that someone had beaten him up because he

was gay.

DAVE O'MALLEY, then-Laramie police

chief Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson had

been involved in a serious aggravated assault on two

Hispanic guys that we had investigated the night

before Matt was found. During that investigation

Matt's bank card was found in McKinney's

truck. About 18 hours later we got the report from a

young man who had been riding his bicycle in the country and

had found Matt tied to a fence there.

PATTERSON I called all our mutual friends and after that

was just alone with my thoughts. The early reports

gave some of the basic information: He had been left

overnight in the cold, he was possibly beaten with a

baseball bat, his body was covered with red welts, he

had possibly had his skin burned. I spent that first

night just reliving what must have happened. I cried a

lot. I didn't sleep.

JIM OSBORN, Shepard's friend; then-president

of the University of Wyoming's LGBT organization

I got an e-mail from friends who had been in contact with

[police chief] O'Malley. They said that it

could be a hate crime. I immediately got a second

e-mail saying, "Don't say anything to anybody,

because we don't want to compromise the

investigation. We're still trying to piece

together where Matt was." I said, "I need to

talk to somebody, because I know where he was Tuesday

night: He was at the LGBT meeting with me."

BOB BECK, Wyoming Public Radio news director

and University of Wyoming journalism instructor A

student in my broadcast news class called and said he needed

to go to the hospital in Fort Collins. We had a major

assignment due, and I said, "You'd

better have a damn good reason." He said, "I

can't tell you, but you're probably

going to report on it: A friend of mine was seriously

beaten up."

CATHY RENNA, then-director of community

relations for the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against

Defamation I was in Washington, D.C. I started

getting all these e-mails and phone messages. We heard

from people across the country; they were outraged.

EDWARDS The day after Matt was discovered there was a

joint press conference between the police and the

sheriff's department, and they'd distributed a

press release. After reading it I was motivated to ask,

"Do you think this is a hate crime?" The

sheriff's deputy said yes. The Denver Post

called me that night, and they asked me what went on

at the press conference. I told the reporter that the

sheriff said it was a hate crime. They published that, and

that's when the floodgates opened.

BECK We were covering it like a murder. When

you're in Wyoming, you don't have more

than 15 [murders] a year. Then to go to the press conference

and hear the sheriff call it a hate crime -- whoa.

We'd never had anybody refer to anything in

Wyoming as a hate crime.

JONAS SLONAKER, current Laramie resident I

was 42 then. A friend of mine called me up and said,

"Did you hear about Matthew Shepard? This kid

was severely beaten because he was gay." I was

getting ready to move from Laramie. When it happened I said,

"Oh, I'm glad I'm getting out of

this place."

OSBORN Thursday night I started getting phone calls

from the campus paper. By the next day we were getting

phone calls from Dateline NBC and Good

Morning America.

JASON MARSDEN, Matt's friend; former reporter

for the Casper Star-Tribune I was at my desk in the newsroom. The managing

editor and editor came to me and said there was this

crime in Laramie and the victim was Matthew, whom they

understood was a friend of mine. I was shocked. But I

didn't go home; I put my two cents in about how

to sensitively cover something like this. Sometimes

it's difficult for straight journalists to even talk

about gay people politely in a news story. Simple things

like how to use terms like gay or homosexual in the

right way: an adjective versus a noun.

BECK At the press conference the sheriff described an

image that turned out not to be true: He told us

[Shepard] was tied up like a scarecrow. Someone asked

him, "Do you mean in a crucified state?" And I

think he actually confirmed that. That's the

image we're all left with. It was right on the

heels of James Byrd, who was dragged to death in Texas.

MOISES KAUFMAN, playwright; director of The

Laramie Project I was in New York. I started getting phone

calls--"Did you hear what

happened?"--and then I read it in the newspaper

and I saw it on television. People have spoken about

how we as gay people feel attacked, injured,

constantly in our culture. And that image of that boy tied

to the fence spoke to so many of us about our pain and

about our sense of how we fit into the landscape of

this country. The impact of seeing what this was doing

to the country -- that's when I decided to go to

Laramie and do The Laramie Project.

O'MALLEY The other investigators were feeding me bits and

pieces of information from interviews, like McKinney

coming in, bleeding from the ear, and saying,

"You know, I think I just killed a fag." These

guys almost got celebrity status in the jail,

high-fiving and that stuff. If you've got any

kind of remorse for your actions, that's not

appropriate. The brutality of it--my son was

bigger than Matt when he was in fifth grade. These

hulks pulled him out of a truck and tied him to a fence to

beat him. That showed a huge amount of

cowardice--and a huge amount of hatred.

SCHMIT On the second day, when the details of it all

began to become talked about, parishioners and

students started coming in and talking about it.

Because of how awful and heinous it was, we decided to have

a vigil. At first I thought it might be a very small

number, but there were way too many people for the

number of candles we had.

O'MALLEY The physical evidence was just unbelievable. We

had DNA; we had hairs; we had tire impressions, shoe

impressions, fingerprints, dirt samples, fiber

matches.

SHEPARD The hospital staff told us that even though Matt

was in a coma, he could sense things. We tried to keep

the atmosphere around him light and not the least bit

tragic or dramatic or any of those negative overpowering

kind of feelings. None of the heavy stuff you'd think

would go on went on, because we were trying to hold it

together for Matt.

RENNA I got off the plane in Laramie and drove

immediately to the Newman Center vigil. Matt was

hanging on in the hospital at that point. You have to

understand: This town's population was 25,000 and

change--there were 1,000 people at this vigil. I

was blown away.

OSBORN The Newman Center vigil was absolutely

overpowering. Candles and flashlights and families,

people with children, university officials, people

from the religious communities. Random citizens who just

showed up. It was amazing to see the breadth of people

supporting us, just feeling the impact of

Matt's attack. People said things that to this day

touch me. Dr. [James] Hurst, the vice president for student

affairs at the time, said, "I have, in my quiet

moments, simply wept." This was someone who had

never met Matt but was so saddened by what had happened.

SCHMIT I found out that Matthew was gay. Did it give me

pause? No. There was a time when I thought we should

call the bishop and let him know what we planned to

do, but I thought, The heck with it--what's

true and correct is true and correct. We invited some

non-Catholic ministers to take part in the vigil, and

they said they wanted to wait until it "all kind of

worked itself out." I couldn't figure

out what that meant. I thought, If you're going

to respond to people's needs, you have to do it now.

You can't wait.

O'MALLEY Prior to this case I wasn't hugely

homophobic, but I was mean-spirited. I bought into the

jokes and the myths and stereotypes of the gay community.

Because of what happened, I was forced to interact with that

community. Quite frankly, I started losing my

ignorance. Did I reevaluate my beliefs in that first

week? In the old country we'd call that a no-shitter.

It didn't take very long at all for me to

realize that I was dead wrong.

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM, author I went to the

candelight march in New York City. I'd been working

with ACT UP for years; a group of us had experience

with moving large numbers of people down the street,

negotiating with the cops. There were 4,000 people.

Everybody was in front of the Plaza Hotel, and the cops

said, "You're going to have to take

these people down the sidewalk." We said,

"That's crazy, it's not safe. Look, you

move traffic to half the street, and we'll take

the other half." So 35 to 40 of us went into the

street, and the cops arrested us. We were stuck in

jail for a couple of days. People were arrested for

civil disobedience throughout the night.

KAUFMAN Among those of us in New York, there was a part

of us that kept saying, "I hope he makes it, I

hope he makes it, I hope he makes it." Praying for

his recovery and kind of knowing full well that it was very

unlikely.

OSBORN They were surprised that Matt lived long enough

to get to a hospital, and then that he lived long

enough to see the next day, and then lived long enough

for his parents to get there. It was no end of surprises.

But I really didn't hold out a lot of hope.

SHEPARD We knew the injuries to the brain stem were

irreversible and controlled his involuntary body

functions. There just wasn't a lot of hope that he

would come back to us as Matt, even if he survived in a

comatose state. He just wouldn't be Matt. We

knew he was about to pass away because there were

blood pressure changes. We'd agreed upon a

do-not-resuscitate order. When the fluctuations began,

we didn't try to correct them. We just let Matt

go home.

OSBORN Very early on Monday morning, 4:30 or 5 a.m.,

the president of the university called me; I remember

seeing his name on the caller I.D. I picked up the

cordless phone and just sat down on the floor because I

knew. It was the call I'd been dreading for five

days.

MARSDEN The day he died I wrote a column for the

editorial page outing myself, sort of in passing. I

wanted to record my thoughts about Matt and his life

and what kind of person he was, the deep sadness I had for

the family, and the families of the assailants. There

was no point in doing it without coming out. I

thought, People really need to know that there are

other gay people in this community, how we're

reacting. After, the focus very much became

"Jason Marsden outed himself in the

newspaper," not what I was trying to talk

about.

SHEPARD President Clinton called us and spoke to Dennis

and my son Logan. I didn't speak with him. He

called with best wishes, and it was really very

sincere, hopeful. I couldn't help but feel that here

was a man who understood the gay versus the straight

world and would be instrumental in making things

right. It didn't really turn out that way, but I had

great hopes.

O'MALLEYTo me, every crime was a hate crime. But I saw the

difference with what happened to Matt. We had kids

moving out of Laramie, transferring to other colleges.

There was a huge amount of terror and fear -- I

hadn't seen that before. There are people

killed during liquor store robberies every day in this

country, but I never think twice about going to the

liquor store. It's a different kind of a motivation

and a different kind of impact. I've now been

to Washington to speak about hate-crimes legislation

on seven occasions. It's something I believe in, and

I'm going to keep working at it. It's

been 10 years, but I fully believe that if this

election goes the way I believe it's going to go, the

Matthew Shepard Act will be a reality in the next 12

months.

MARSDEN Matt was someone I met at a birthday party who

was interesting and smart; he turned out to be a good

friend. I'm gratified the world has maintained

interest in him, but it's incredibly painful to lose

someone from your life. People always say,

"Maybe something good will come from it in the

end," and I always say, "Nothing good will

come from what happened to Matt. Some good may come

from how people choose to react to what happened to

Matt." I don't know if that's a

distinction without a difference. The word anniversary

is used occasionally, and it just jars me. An

anniversary is a celebration. This is not a celebration in

any way. It's a milestone.

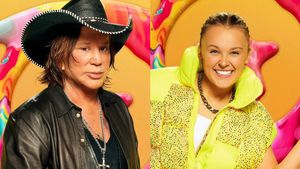

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4