The night before Election Day, a black woman walked into the San Francisco headquarters of the No on Proposition 8 campaign. Someone had ripped down the No on 8 sign she'd posted in her yard and she wanted a replacement. She was old, limping, and carrying a cane. Walking up and down the stairs to this office was hard for her.

I asked why coming to get the sign was worth the trouble, and she answered, "All of us are equal, and all of us have to fight to make sure the law says that." She said that she was straight, and she told me about one of the first times she ever hung out with gay people, in New Orleans in the 1970s. "I thought I was so cool for being there, and I said, 'You f****ts are a lot of fun!' Well, that day I learned my lesson. A gay man turned on me and said, 'A f****t is not a person. A f****t is a bunch of sticks you use to light a fire.' "

The next day, Barack Obama was elected president, and gay marriage rights in California were taken away. At the same time, Arizona voters amended their state constitution to preemptively outlaw gay marriage. Florida went further, outlawing any legal union that's treated as marriage, such as domestic partnerships or civil unions. Arkansas passed a vicious law denying us adoption rights.

The combination of Obama's win and gay people's losses inflicted mass whiplash. We were elated, then furious. I'd spent the week in the No on Prop. 8 office in the Castro, a neighborhood where our defeat was existential. For the next few days, wherever I went--barbershop, grocery store, gym, bars--I heard people talk of almost nothing else. Incredibly, strangers on the street walked up to me and started conversations about Prop. 8. Taking the long view, some found hope and consolation: 52.3% of Californians voted against us, but 47.7% voted with us, which was the closest we've ever come to winning a ballot measure for marriage equality in the state. Other election results were even more encouraging: In New York State, where a marriage bill is pending, we won enough legislative seats to secure a pro-equality majority; Connecticut voters rejected a constitutional convention that could have reversed that state's legalization of marriage.

Still, the election was a blindsiding reminder that the majority of voters, even in a state as liberal as California, still see gay people as second-class citizens. These past few years we've made so much progress that we'd begun to think everybody saw us as we see ourselves. Suddenly we were faced with the reality that a majority of voters don't like us, don't think we're normal, don't believe our lives and loves count as much or are worth as much as theirs.

History compounds the insult and suggests hypothetical scenarios rendering the mixed result of this election even more absurd. If the California supreme court and the U.S. Supreme Court decisions overturning antimiscegenation laws -- Perez v. Sharp and Loving v. Virginia -- had been blocked by popular vote, Barack Obama might never have been born. His parents would not have been able to marry in several states (although Hawaii, where they were married, had never enacted a law against interracial marriage).

The morning after the election, I wanted to celebrate for Obama, and I also felt an awful sense of loss. Then it hit me that my own angry confusion was nothing compared to what my black gay friends were probably feeling. Moreover, their wound was inflamed by ugly speculation about the racial implications of Prop. 8's passage, which began that day. Many commentators noted that 70% of gays voted for Obama but 70% of blacks voted for Prop. 8. From this fact, some drew a race-baiting, false conclusion that blacks lost the election for us. Yet African-Americans represented just 10% of Californians voting, and the difference between full equality and abject disappointment here was so small -- 2.3% of the total vote -- that it would be possible to blame almost any group of voters for it. Prop. 8 won by vast majorities in many places south of San Francisco and among Republicans; and according to figures available at press time, less than two thirds of registered voters in San Francisco and Los Angeles even bothered to show up to vote, because polls so unambiguously predicted Obama's win.

Moreover, at the eleventh hour, the "Yes" folks flooded black communities with literature and phone calls falsely suggesting that Barack Obama supported Prop. 8 (though accurately stating that he is opposed to gay marriage), adding significant confusion to an already confusing ballot question. Some of my most liberal straight white friends in San Francisco still weren't clear the day before the election that "Yes" meant "No," that a vote for Prop. 8 was a vote against marriage equality.

To blame this loss on black people would be a terrible mistake, and it would only increase enmity between gays and blacks. African-American leaders in the Congressional Black Caucus -- particularly Barbara Lee -- and state leaders such as former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown worked hard on our behalf; many of them were quicker to come to our defense than their white peers. And they did this even though white gay people have never, en masse and in force, showed up to support them and their issues. The work of our black allies created an immense reservoir of opportunity and possibility for the movement going forward. It should not be squandered for the cheap satisfaction of finding a scapegoat.

It's impossible not to imagine what might have happened if the civil rights of African-Americans, Hispanics, women, or any other minority had been reversed by public referendum. If any other group of people in America had their fundamental rights subjected to popular vote, there would be universal outrage in this country.

We voiced our rage ourselves. In the days following the election there were protests, including some involving minor violence, in places as small as Laguna Niguel, as large as Los Angeles, and many other locations, including San Jose, Oakland, Sacramento, Palm Springs, Long Beach, Santa Barbara, San Diego, several Orange County communities, and Salt Lake City. At press time, another was planned to take place outside the Manhattan Mormon Temple in New York City. Like the protests at temples in Los Angeles and Salt Lake, this was aimed at heightening awareness of the role of Mormon money in this race. (Reliable estimates suggest that more than 40% of the funding for Prop. 8 came from Mormons, and much of that money came from Utah.)

In San Francisco the protest on November 7 was oddly joyful. It came together virally on Facebook and via blogs, and drew a crowd of people who were on the surface pretty much indistinguishable from what you'd see in any suburban church on Sunday. News reports mostly showed the same types of images the media insists on using when covering gay pride parades. A marching band played show tunes -- "If My Friends Could See Me Now" -- and a drag queen screamed, "The problem with living in a bubble is that bubbles burst !" She was fierce, and I was moved, but I also wondered why she was the one on the news that night, why this movement still doesn't have a Martin Luther King Jr., a telegenic, brilliant spokesperson to whom all of America can relate. The dedication of movement organizers has brought us a long way, but we are now in desperate need of a willing leader with solid media sense, a palpable inner core, an ability to navigate the game of hardball politics, and the balls to step forward and be our public face.

Whoever you are, it's time to come out. Because, as I was reminded the morning after the election, it's faces -- not arguments -- that will close the deal on marriage equality. I was in a taxi on Market Street, and as we passed City Hall the driver mentioned the protest and asked me what I thought of gay marriage. I flipped the question back to him. "I used to be against it," he answered, "and then I saw it. When I saw it I understood."

The driver, whose name was Ali, told me he was from Yemen and he's straight. When a friend recently came to visit him, the two went sightseeing. "I took him to City Hall and we saw all these people getting married. We saw men marrying men and women marrying women," Ali said. "I was really surprised. They were so happy."

His voice was low and unsentimental, but the first syllable of "happy" was so full of amazement it shot almost an octave higher than the second. The word seemed to crash down through a roof. He kept repeating it. "I have seen a lot of things," he went on. "I have seen bisexuality, gay, lesbian. The sexy parts. I had never seen the love before. But I saw these two guys get married and I realized, This is their happiness." As he turned onto Castro Street, Ali said, "Everybody has a right to their happiness. Nobody should have the power to take your happiness away."

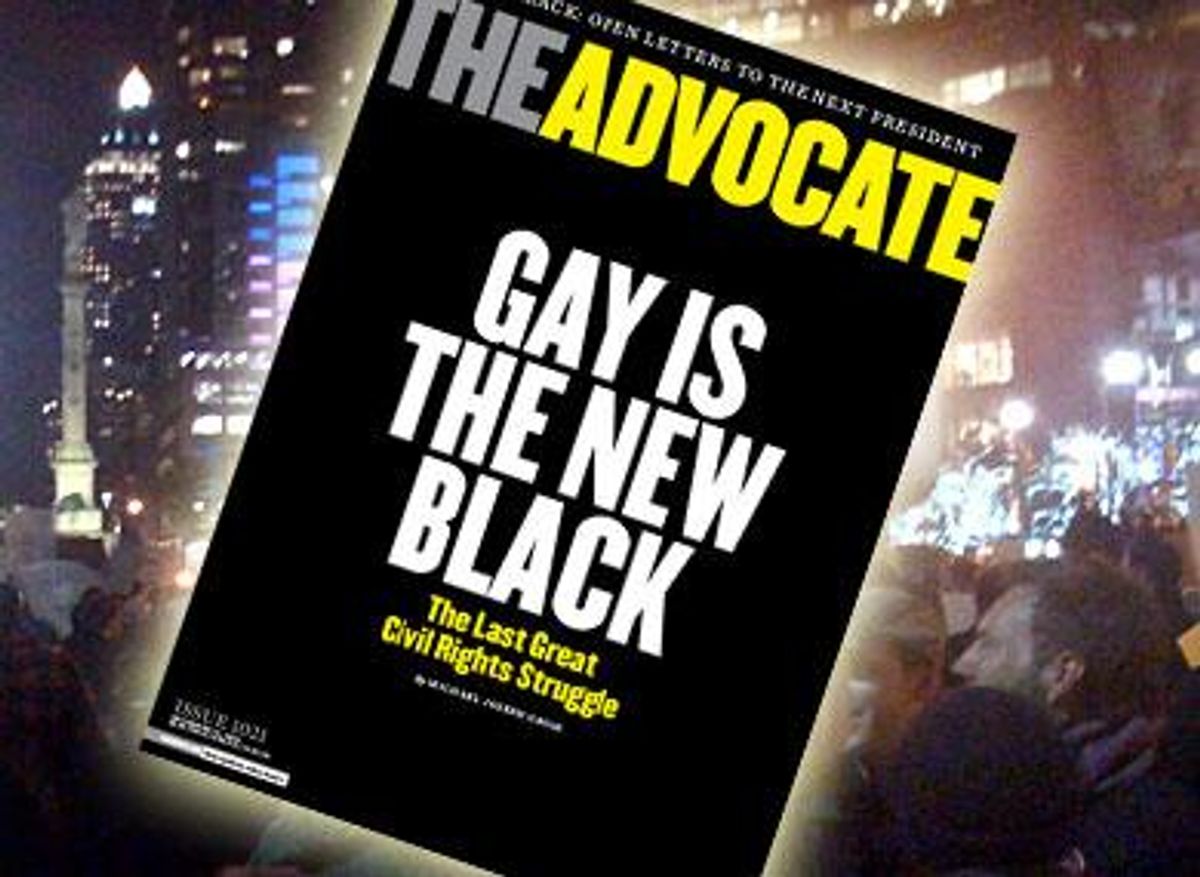

We gave into another post-election temptation too. Many drew a simple parallel between our struggle and the black civil rights movement. Signs at protests said, "I have a dream too," "Welcome to Selma," and "Gay is the new black."

There's something to this, but it's dangerous territory, and we have to be careful not to lose our bearings here. Gay is the new black in only one meaningful way. At present we are the most socially acceptable targets for the kind of casual hatred that American society once approved for habitual use against black people. Gay is the dark pit where our society lets people throw their fears about what's wrong with the world. (Many people, needless to say, still direct this kind of hatred toward black people too. But it's more commonly OK to caricature and demean us in politics and the media in ways from which blacks are now largely exempt.) The comparison becomes useful, though, in forcing us to consider the differences between our civil rights struggle and theirs.

Except in a few statistically insignificant cases (the gay kid who happens to be the child of gay parents), being gay begins with recognizing your difference from the people with whom you have your earliest, most intimate relationships. As such, it's an essentially isolating experience and therefore breeds in many gay people certain qualities--such as independence and perfectionism--that can undermine our ability to cooperate and compromise with others. Though some of us were lucky enough to find role models, mentors, or gay friends early in life, we weren't born into the kind of beloved community that the African-American church aspires to be. Today, the church is still the strongest black American institution, and though it is far from a perfect place, for its members it's a cradle of love and shelter from oppression.

Our oppression, by and large, is nowhere near as extreme as blacks', and we insult them when we make facile comparisons between our plights. Gay people have more resources than blacks had in the 1960s. We are embedded in the power structures of every institution of this society. While it is illegal in this country to fire an African-American without cause and in most places it's still legal to fire a gay person for being gay, we are more likely to have informal means of recourse than black people have. Almost all gay people have the choice of passing. Very few black people have that option. Of course, we shouldn't have to make that choice, and our civil rights struggle is about making sure that we don't have to.

On a deeper level, though, the gay civil rights struggle is about preventing discrimination based on our proclivity to love, as distinct from the messier foundation of racial discrimination, which primarily has to do with protecting white privilege and wealth. No one would deny that fear of mixed marriages significantly inhibited the progress of the black civil rights movement. (Blacks won employment and voting rights a full three years before the Supreme Court finally struck down miscegenation laws in 1967.) But love and sex were not, as is the case with gay civil rights, unambiguously the heart of the matter. This is the reason our progress has been slow: Love cannot be understood in the abstract. You cannot understand it until it touches you or you find your way into its orbit.

We have to stop rage from getting the best of us right now, and keep love at the fore of everything we do and say in this battle. We are close to winning everything we want. We are so close that we do not have time to rehash the Malcolm/Martin struggle between anger and peace, force and nonviolence. Let's call the Mormons out on the campaign of lies they funded, but let's find a way of doing it that steers clear of hatred. Enough with the "Fuck Mormons" signs. Some Mormons are gay, not all Mormons voted against us, and a few of them publicly put themselves on the line for us.

We are taking to the streets now--while writing this, I received an e-mail from a friend pointing me to an online organizing of protests on November 15 in all 50 states -- and we are angry, probably not least at ourselves for our own complacency and cowardice, for not working as hard as we could, for not giving as much as we could, and for letting so much slip from our grasp. Let's find a way of channeling the passion of this flash point and harnessing this energy for the long haul so we can do the hard work of claiming the full rights and realizing the full lives that we know we can have.

When you use f****ts to start a fire, you don't just dump a bunch of twigs on a few logs and hope something catches. You choose your tinder carefully, you bundle it vigilantly, you place it carefully -- then, and only then, you set the fire.

On Election Day the No on 8 campaign prepared statements for its website to post in the event of a victory or of a loss. One of the people in charge of this task left the office that night with her eyes full of tears. "I am so angry," she explained, "that they dragged us into this shit. And they shouldn't have. We already won, and still, they are making us fight for what we already won." She pulled herself together. "But we're going to win. We have to win. I am 23 years old," she said, "and this is my civil rights battle."

For a moment I was overcome with admiration for this woman's passion, and at the same time, with a shiver of thought that, if it were made of words, would consist of something like the phrase You are going to die. It was a keen intimation of mortality, of the sense in which our lives, even in the moments of our most focused and profound presence, are merely fragments of the endless story of the human struggle for dignity. A friend in Los Angeles said he saw a sign at one of the protests saying, "Rosa sat so Martin could march so Barack could run." For us, as for the African-Americans who lived through the '60s, many apparent failures will, in retrospect, clearly be progress. We lost a lot on this Election Day, but we gained a lot too. Not least was a president who has shown almost every sign of goodwill we could wish for and a Congress eager to follow his leadership where we are concerned.

A lot of us have been fighting for as long as we can remember, trying to keep the world from seeing us as f****ts. Maybe it's time to give up that fight and choose another one instead. Go ahead and be a f****t, in a way that shows the world that a f****t is a person. Start a fire, but let your fire be a beacon. Let your fire burn away your hate, and it will burn away the hate of your enemies. Let your fire be the light that shows your love. If you do that -- if we do that -- we will win the world, and soon.