If classical

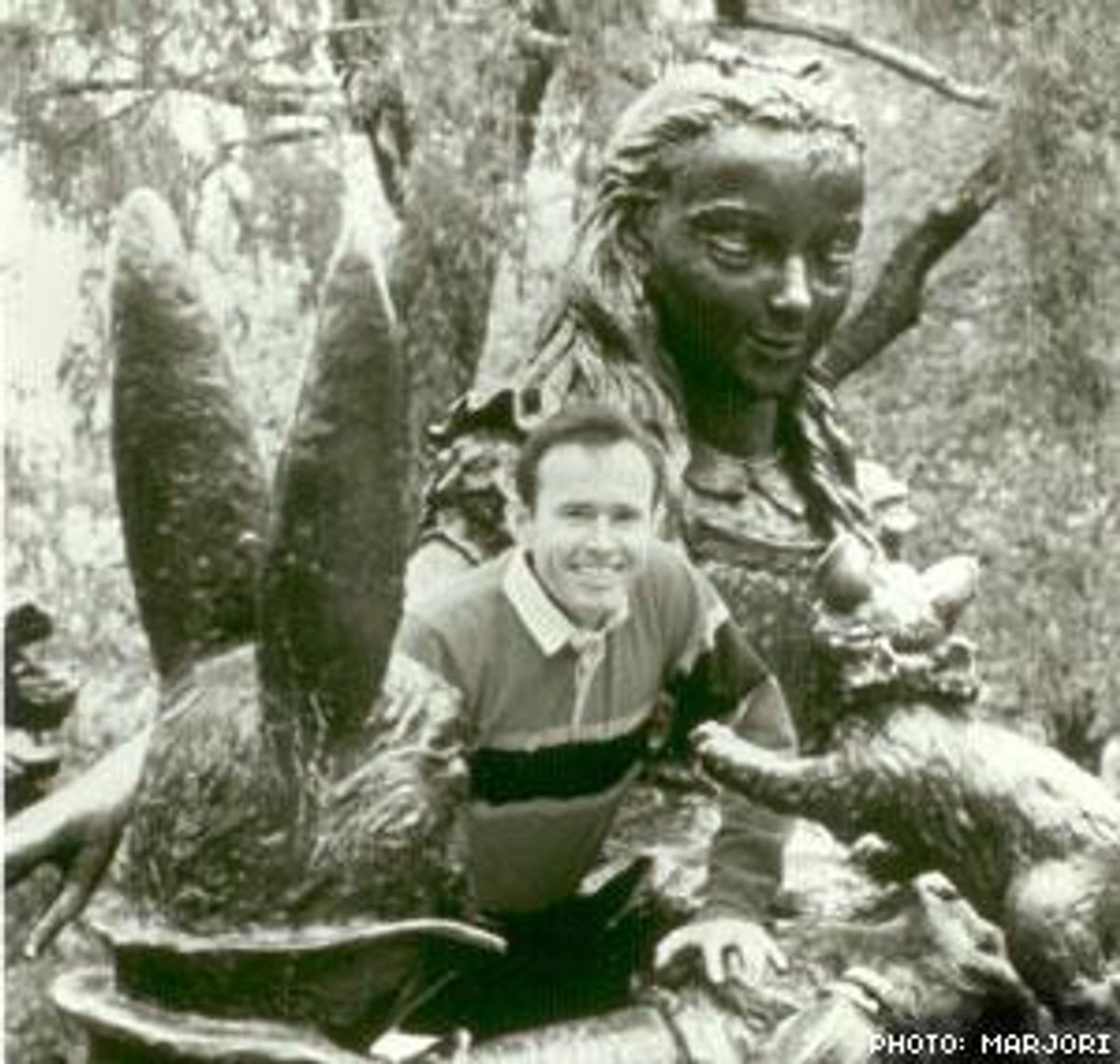

music has a living gay icon, it is composer David Del

Tredici. Generally regarded as the founder of the

neoromantic movement, the California native has

garnered numerous awards during his long and busy

career. His early output was primarily focused on the works

of Lewis Carroll, whose writings he admits he

is somewhat obsessed with. Among these works are

the opera Final Alice, his best-known work, and

his Pulitzer Prize-winning "In Memory of a

Summer Day," part one of his song cycle Child Alice.

Since his

recovery from alcoholism in the late '80s, Del

Tredici has not only embraced his gayness but has

celebrated it in his art to an extent that few other

gay composers have. Now in his 70s, the still

energetic Del Tredici will premiere two new pieces -- My

Favorite Penis Poems, a musical interpretation

of six gay poets including Edward Field and Allen

Ginsberg, and Wondrous the Merge, an

interpretation of a work by the late gay poet James

Broughton -- December 4 at Symphony Space in New York

City.

Advocate.com:You're known as the father of neoromanticism. Is

that a title you accept?David Del Tredici: I accept it, and it's

probably roughly true.

Do you feel a connection with Lewis Carroll? Absolutely. He was a little much for that time,

he had this love of little girls, took obsessive

photos... It connected with my own sense of being

a gay pariah. People always ask, "Why did you go on

with this for so long?" and I think it's

because I made this identification with Carroll.

When did you start embracing gay culture in your art? Well, first I celebrated the work of a

"closeted" man, Lewis Carroll. After

this I became very successful. Right after the time I wrote

Final Alice I became an alcoholic. When I came

out of alcoholism I started to explore myself and do a lot

of therapy, and in the course of that it kind of

opened me up to my own gayness, and I celebrated that

in a way I had never done, bringing it into my music. I

realized that there wasn't a lot of celebration of

being gay in classical music. So many great American

composers were gay -- Copland, Barber, Menotti,

Bernstein -- why not celebrate it? I was very close with

Copland, Barber, and Menotti. In their private life it was

one thing, but as soon as they went public there was

no mention of it.

Tell us about your relationship with Aaron Copland. I was at Tanglewood, an American institution,

sort of a cross between a music school, camp, and

artists' colony, and we became friends, but never

lovers. For 20 years I guess I absorbed his way. He had a

wonderfully direct, uncomplicated way of writing and

talking about music. At the time I was teaching at

Harvard, which is a very complicated place, very

intellectual. Copland was always my mainstay. I thought he

was the best composer around.

You also developed a friendship with Allen Ginsberg. I got to know him at a couple of parties. He

tried to pick up a boyfriend of mine once -- I was

very annoyed. I was a lot younger and cuter, I

thought, but [Ginsberg] was very persistent and had a lot of

charisma, this sort of Buddhist pick-up technique.

Allen was wonderful. I said, "I want to set

some of your poetry." He had just [done a reading of]

some of his poetry, so he said "Here,"

and he gave me the book he read from. So I became kind

of a fan.

Was that at the point in your life that you were

becoming very out? Well, this was when I was drinking. I was

looking for gay poetry I could connect with. It all

got started because I got very interested in the Body

Electric [a San Francisco-based encounter group for

gay men], which really opened me up. It hooked up

in me the erotic and the creative. I had this ecstatic

week with the Body Electric. I started spontaneously

setting these poems [to music]...really fast. This was

the first poetry I'd set in 20 years that

wasn't by Lewis Carroll! It changed my

direction completely; I started to write song cycles. This

one week at Body Electric did something to me!

You grew up in a time when homosexuality was not

something that was talked about. How hard were your

earliest coming-out experiences? I was raised Catholic, and I didn't come

out until my senior year in college. I went to

Princeton and I had a roommate who fell in love with

me whom I couldn't stand. It was terrible. I came

home and told my parents that I had given up the

church and I was queer and I didn't want to go

back to Princeton. So they said OK. They were supportive,

but they said, "We think you ought to go to a

psychiatrist." That was a very depressing year.

Then I met a guy and we went to New York together. It

was relatively easy; my parents accepted it. I'd

always been my own man. I was, in the family, the only

queer, and the only alcoholic, so they knew I was from

another planet.

As you mentioned, you've been writing lots of

songs in recent years. Does this represent a shift in

the form of your work? Well, earlier I was writing big pieces with

voice -- I really couldn't call them songs. The

Alice pieces are like little operas, but more

recently, since the Body Electric experience, I've

written "real" songs; also I've

written, suddenly, again for piano.

Like your recent piano piece S/M Ballade. A wonderful pianist friend of mine named Marc

Peloquin commissioned me to write that for him. It

seemed like such a tortured, hard piece that it seemed

like an S/M experience, so I decided to call it that.

But there are lyrical moments... Well, even in the S/M experience you can pause

to relax!

Another recent work of yours, Queer Hosannas, is

written for a male choir. How did you come by

the poetry included in this piece? I went on a hunt for it. I'm a big fan of

the poet Antler, a disciple of Ginsberg. His poetry,

most of it, is extremely sexual. I'm always partial

to him. [His poem "Whitmansexual"] is kind of

a litany. Any poem that ends with a rhyme about making

music, I like. It touched me. I wanted to celebrate

being sexual rather than spiritual.

You seem to be exploring the sexual more and more

in your work lately. I'm doing here, in New York, in December

a little piece called My Favorite Penis Poems, songs

for soprano, baritone, and piano -- and I've

had trouble getting singers who will do it. One of the

poems is by Allen Ginsberg and it's extremely

pornographic!

Final Alice is probably your best-known

work. Has your style changed much since you wrote

that more than 30 years ago? After Final Alice I wanted to write a big

piece that lasted an hour that's all tonal, so I

wrote "In Memory of a Summer Day," which

won the Pulitzer Prize in 1980, so after that I stayed

tonal -- I found the language I was comfortable with. I feel

like I invented tonality! [Pioneering atonal composer]

Arnold Schoenberg said, "There are still fine

pieces to be written in C major." I feel tonality

is still very explorable.

- You can read

more about David Del Tredici's life and

works, get current news about him, and sample some of

his music at his website.