In June the governing body of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent a letter to every Mormon congregation in California asking that a message be read to members at Sunday services stating that "marriage between a man and a woman is ordained of God," and "local church leaders will provide information about how you may become involved in this important cause." The cause was Proposition 8, and church members were implored to "do all you can to support the proposed constitutional amendment by donating of your means and time."

Mormons heeded the call. Not only did they donate what appears to be a majority of the funds raised by the Yes on 8 campaign -- an estimated $20 million, according to Prop. 8 opponents, much of it from out of state -- but church members also volunteered thousands of man-hours in support of the amendment. Though the Mormon Church avoided a visible public role in the campaign, it did formally join the coalition of religious groups supporting the amendment, and a prominent member, Mark Jansson, served on the Yes on 8 executive committee. (Jansson was one of four signatories to a public letter threatening a boycott of businesses whose owners contributed to No on 8.)

Mormons make up only 2% of California's population, so the fact that they played such an outsize role in the Yes on 8 campaign testifies to their rigid and efficient organization as a religious community. Because the church requests that members tithe 10% of their annual income, LDS leaders are able to gain an accurate picture p of how much their congregants earn. With this information in hand, bishops in local communities went from house to house in California asking for specific amounts of money for the Yes on 8 campaign -- an incredibly effective fund-raising tactic. Mormons boast high rates of involvement in church-related activities, including commitments that can be quite demanding, such as missionary work, whereby members spend up to two years proselyting, often in far-flung overseas locations.

This individual discipline, obedience to hierarchical authority, and experience in exhorting people to join the faith comes in mighty handy for mass political organizing. Indeed, Mormons campaigned heavily for former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney's unsuccessful 2008 presidential bid, especially in the key first primary state of New Hampshire. And it's Romney's potential future presidential aspirations, as well as Mormonism's tortured history in America, that has led some to speculate that the church wasn't just advocating for "traditional" marriage in the Prop. 8 fight. Perhaps it was also deliberately flaunting its power as a force to be reckoned with --showing both the broader religious right and the Washington political scene what it can do.

Ever since its inception in the early 19th century, Mormonism has been derided as a cult by other Christians, especially evangelicals. "They're very insecure people," says Alan Wolfe, director of the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life at Boston College. And the reaction to Romney's campaign showed why this anxiety might be justified. From the start, Romney had difficulty attracting the much-needed support of evangelicals and was shocked at the level of anti-Mormon sentiment he experienced campaigning in heavily Protestant areas. "There's a lot of resentment amongst members of the church," says Clayton Christensen, a Mormon and professor at Harvard Business School, about the level of hostility that materialized during Romney's candidacy. "Christ actually said you should love your enemies and do good to people who spitefully use you. And yet, with the evangelicals in the presidential campaign, those guys really showed that they are the ones that aren't Christian."

Mormons have expressed similar disbelief at the level of anger voiced by the gay community in the wake of Prop. 8's success. In response to nationwide protests staged outside Mormon temples, the church released a statement bemoaning that it had been "singled out for speaking up as part of its democratic right in a free election." Church members feel "genuine alarm" at the hubbub created by their efforts, according to Damon Linker, a former editor of the conservative Christian public policy journal First Things and the author of The Theocons: Secular America Under Siege. And that's not surprising, considering that Mormons have long been involved in the movement to ban same-sex marriage -- and yet are only now facing massive scrutiny for it.

Ascribing cynical motivations to the LDS church's behavior is intriguing, but the contention that it became involved in the fight over Prop. 8 as a way to impress is belied by Mormon history. First, Mormonism has never been particularly welcoming of gays and its doctrine proscribes homosexuality as a sin. Nor is it the case that the church ignored same-sex marriage until this past summer. The day before Prop. 8's passage, a seven-page internal LDS memo was posted online showing just how prescient the church was on the issue. Addressed to M. Russell Ballard, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (men regarded as living prophets by LDS members), the memo presents a thorough argument for why and how the church should become involved in the movement to prevent same-sex couples from marrying.

The memo, dated March 1997, was written in response to continuing developments in Hawaii, where in 1993, the state's supreme court ruled that the denial of marriage to same-sex couples was discriminatory. Anticipating a national legal and electoral fight over the issue, its author supported the involvement of the church in fighting back attempts to legalize marriage equality. The memo not only stressed the importance of working with other religious groups but also cautioned that more mainstream Christian denominations ought to be the public face of the campaign due to concerns that Mormonism was still viewed with suspicion by the general public. Describing a meeting that then-LDS president Gordon Hinckley attended, the memo states that Hinckley "said the church should be in a coalition and not out by itself," and cites a poll conducted by Richard Wirthlin, a former senior adviser and pollster for Ronald Reagan and a leading LDS figure, which found that "the public image of the Catholic Church [is] higher than our church." The conclusion of the memo's author: "If we get into this, they are the ones with which to join." The church had been nominally involved in the marriage debate prior to the writing of this memo; in 1994 it issued a formal statement against gay marriage, and in 1996 local congregations across Texas urged members to join an antigay organization called the Coalition for Traditional Marriage.

A great deal of the intellectual work of the traditional marriage movement was done at Brigham Young University, which is owned by the Mormon Church. James Ord, a gay Mormon living in California who describes his status with the church as "inactive," graduated in 2004 from BYU's law school, where he worked alongside professors Richard Wilkins and Lynn Wardle. The two have been prominent players in the anti-gay marriage movement and, according to Ord, began crafting the legal strategy to oppose same-sex marriage almost immediately after Canadian courts in Ontario issued a series of rulings in 2002 that laid the groundwork for marriage equality in the province and, eventually, the country. For the next two years Ord "attended meetings, forums, and academic discussions where the language for these amendments was floated and debated."

A rapprochement between mormons and the religious right at large does not appear to be in the offing, despite the LDS Church's hard work on Prop. 8. With marriage, there is "far more at stake for Mormons than there is for a Catholic or evangelical," Linker says. Ironically, in light of Mormonism's polygamist history, he points to its contemporary emphasis on the heterosexual family structure as the primary reason for its involvement. "Mormons are different than other factions on the religious right because their theology emphasizes a traditional male/female family with kids in a way that goes far beyond most other groups, whether they be evangelical or Catholic," Linker says. According to Mormon dogma, marriage extends into the afterlife and couples continue to have "spirit children" who populate extraterrestrial worlds.

The church is also selective in the battles it fights. For instance, Christensen says, the church stayed out of the dispute over same-sex marriage in Massachusetts because it didn't think it could defeat the measure in one of the country's most liberal states, even though then-governor Romney was leading the effort to do just that. Contrast the church's judicious decision in the Bay State with its 2000 campaign in support of California's Proposition 22, a statute defining marriage as between a man and a woman. That measure passed with 61% of the vote, its success was never in doubt, and it occurred a full three years before Massachusetts ruled in favor of marriage equality. Given the uphill environment activists faced then, their outcry was understandably muted compared to the devastating sense of loss felt in November's bruising. And since the church didn't face any backlash in 2000, according to Ord, its leaders felt confident about rejoining the fight this time around.

But while Mormons may be bewildered at the outrage directed their way now, it would be wrong to conclude that the church has been so chastened by the reaction that it will stay out of future political battles. For one thing, Mormon doctrine remains steadfastly opposed to same-sex marriage. "To allow gay marriage is to fundamentally misconstrue what [they] are ordained by God to become," Linker says. And Mormons have suffered far worse in their history than mere protests or the occasional anthrax scare. "I think we attempted to work in the process to do what we think is right in society and in the eyes of the Lord," Christensen says. "I don't feel any kind of sense that we made a mistake."

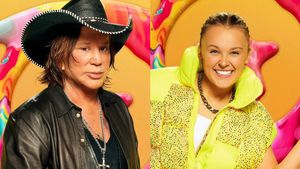

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4