Sirdeaner Walker, who

has survived domestic violence, homelessness, and

breast cancer, knew death could come suddenly -- but

she could not have predicted it would find her 11-year-old son

first.

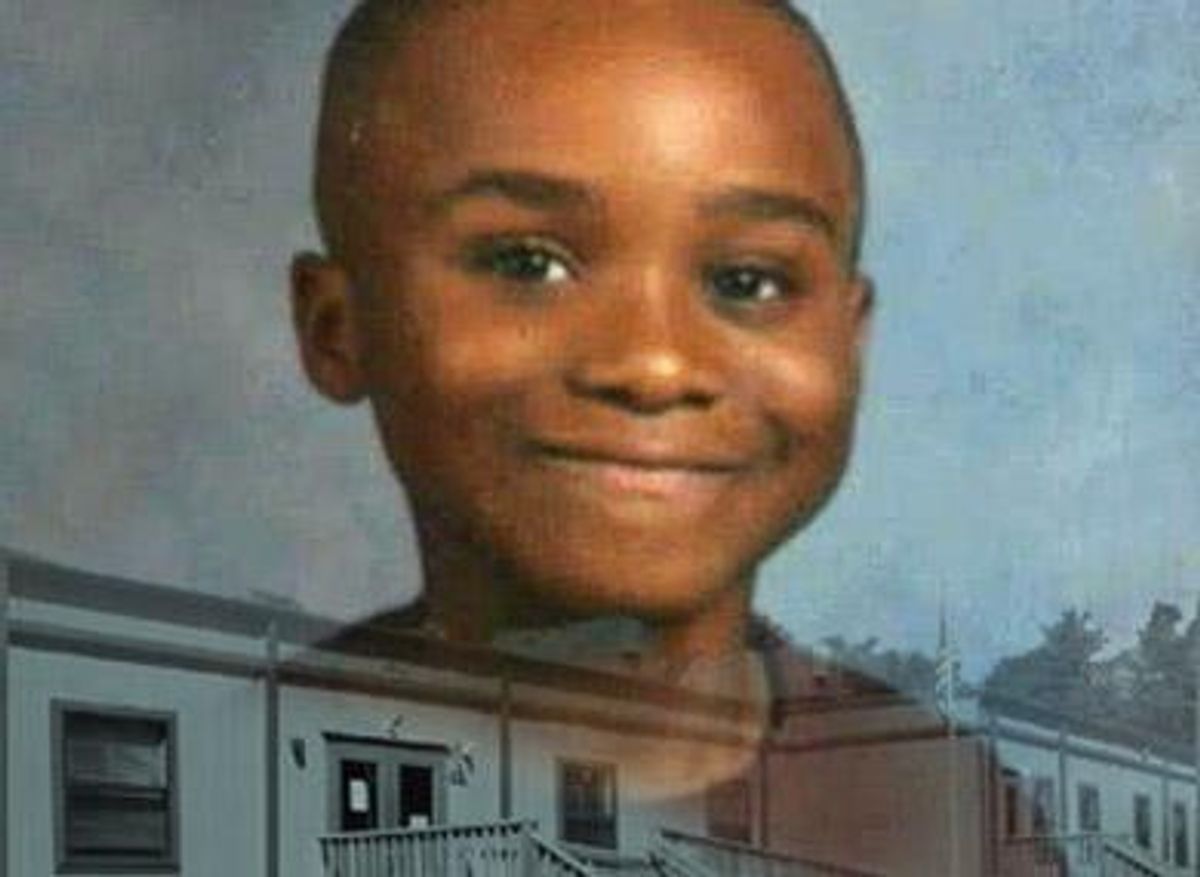

Carl Joseph

Walker-Hoover was a sixth-grader at New Leadership Charter

School in Springfield, Mass. There, many of his classmates were

initially strangers, as few of his friends from Alfred Glickman

Elementary followed him.

On April 6, Sirdeaner

Walker came home, walked up the stairs to the second floor of

her home, and saw her son suspended from a support beam in the

stairwell, swaying slightly in the air, an extension cord

wrapped around his neck, according to police. He apologized in

a suicide note, told his mother that he loved her, and

left his video games to his brother.

Walker said her son had

been the victim of bullying since the beginning of the school

year, and that she had been calling the school since September,

complaining that her son was mercilessly teased. He played

football, baseball, and was a boy scout, but a group of

classmates called him gay and teased him about the way he

dressed. They ridiculed him for going to church with his mother

and for volunteering locally.

"It's not just

a gay issue," Walker said. "It's bigger. He was 11

years old, and he wasn't aware of his sexuality. These

homophobic people attach derogatory terms to a child who's 11

years old, who goes to church, school, and the library, and he

becomes confused. He thinks,

Maybe I'm like this. Maybe I'm not. What do I

do?

"

His birthday, April 17,

falls this year on the 13th National Day of Silence, a day on

which individuals observe vows of silence for students

bullied at school.

But instead of silence,

Walker wants action from the school, which she said

continuously ignored her, chalking the situation up to student

immaturity. She said that every day her son left for school, he

walked into a "combat zone" assigned to him because

of his inner-city address. But he would not point a finger at

specific classmates for fear he'd be called a

"snitch."

Walker said that she is

angry with teachers and administrators for not taking action,

and she called on the state of Massachusetts last week to probe

the school, hoping she might prevent other children from

feeling as her son did.

"A lot of parents

don't know the avenues open to them. A lot of parents

don't know where to turn," Walker told

The

[Springfield]

Republican

.

In the days

following Walker-Hoover's death, parents and community

members have grown increasingly critical of the school system's

approach to bullies and peer abuse, further fueled by

administrators refusing to comment to local media.

Hilda Clarice Graham,

an expert on bullies and a school safety consultant with

International Training Associates, said students often use

assumed sexual orientation as a main weapon against one

another. "It's the hammer that hurts the most and is the

most vulnerable and hurtful thing going," she said.

Nearly half of children

between the ages of 9 and 13 have been bullied, and nearly 10%

of those students say it happens on a daily basis, according to

a study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In

a 2007 Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network study, 86%

of LGBT students said that they had experienced harassment at

school during the previous year.

Days prior to Carl

Walker-Hoover's suicide, he confronted a female bully who

verbally accosted him. The event served as an apparent catalyst

to Walker's suicide. The school's response was to have the two

students sit beside one another during lunch for the

next week to encourage conversation.

Graham says the

school's response is not ideal because "for

mediation to work, there must be equal power." She said

bullies' goals are to hurt, and to depend on them to feel

remorseful is not an effectual way to deal with them -- that

victims are at a disadvantage when trying to make peace

alone.

Graham added that

schools should handle bullying on a small scale to avoid

large-scale responses to tragic events.

"It's the most

dramatic call to action a school can receive," she said.

"Parents want a guarantee that this will never happen

again."

Many residents came out

in support of the Walker family in a school-sponsored vigil

last Thursday night. Walker says school officials didn't

invite her to the event. She said she heard from others but

chose not to attend.

School superintendent

Alan J. Ingram said on Thursday that cases of bullying must be

addressed quickly and fairly, but added that many of the

state's charter schools are autonomous and have their own

policies. He said 11 of the system's schools have

bullying-prevention programs, but most operate in elementary

schools.

Peter J. Daboul, the

newly elected chairman of the school's board of directors, said

the board will have an emergency meeting to review the

circumstances surrounding Walker-Hoover's suicide. He said

the school follows the Springfield Public School

System's protocols for dealing with bullies.

For now, Walker says

she worries about her son's best friend, a heavy girl with whom

Walker-Hoover would have lunch. Walker said the

girl is still teased for her weight.

"By whatever means

[are] necessary, I'm going to get the message across that

the taunting has to end in the schools," she said.