I had been warned:

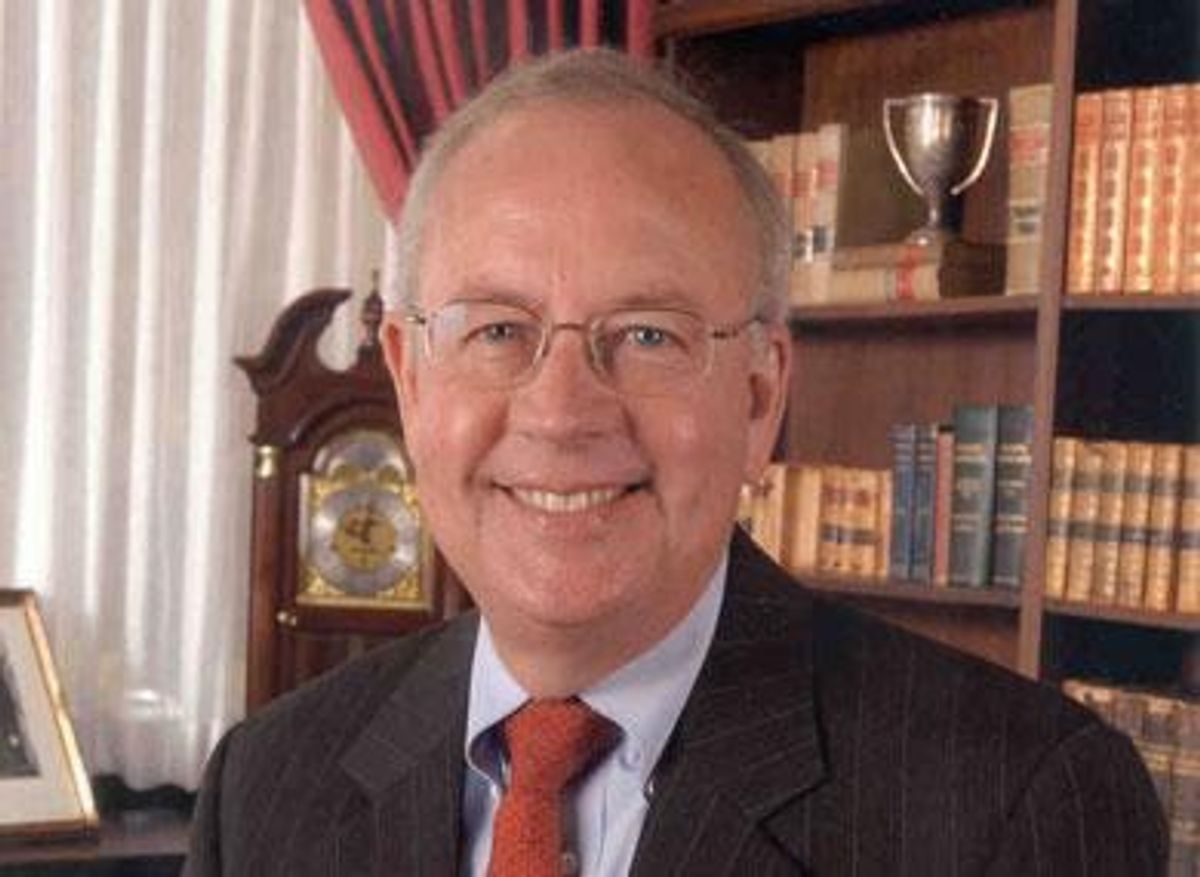

Don't be seduced by Ken Starr's charisma and charm. The advice

struck me as odd. "Charisma" and "charm"

did not rank high when playing free association with "Ken

Starr." But my experience of charming fundamentalist

preachers who would smile as they consigned me to the

netherworld for my sexual orientation put me on

notice.

When I began thinking

in more objective terms about Ken Starr as a charming fellow,

it started to make some sense. Certainly, Pepperdine University

School of Law in Malibu, Calif., would not have chosen

a blustering, brash, hyperpartisan ideologue to be its dean.

They needed not only someone with huge name recognition to

bolster its emerging national reputation and ranking, but also

an individual with a persuasive charm to court alumni donors.

Besides, it was only reasonable to assume that given his

success in life, Mr. Starr undoubtedly possessed social grace

and sound political instincts.

I was mentally ready.

He wasn't going to seduce me. No way. The mission I shared with

four fellow Pepperdine alumni was clear. We were determined to

take Dean Starr to task in a face-to-face meeting for his

representation of the pro-Prop. 8 groups before the California

supreme court.

When I first heard the

news that Starr had agreed to take on the case, I was

embarrassed to be a Pepperdine alumnus. My embarrassment became

resistance. I would not stand by as Starr tarred my alma

mater's reputation by associating it with an unjust and immoral

antigay ballot proposition.

I decided to give him

an earful. A few former classmates and I penned a strongly

worded letter to Dean Starr and the university administration,

voicing our collective disappointment and disgust that our

school had become synonymous with the advocacy of a proposition

that would pass judgment on people and make it yet more

difficult for LGBT people to enjoy equal protection. More than

160 alumni felt the same way and signed on to our letter. Two

associate deans at the law school responded with a letter of

their own, defending Mr. Starr and the school. Notwithstanding

their ardent defense, the letter concluded with an invitation

to meet and begin a dialogue on the issues of Dean Starr's

representation and the school's perceived ambivalence toward

LGBT causes.

We accepted.

It's amazing how

disarming a smile can be, especially from someone whom so many

abhor. Yet that's what happened. Mr. Starr walked in and with a

smile and a sense of ease impressed our small delegation of

dissenters as a pleasant, gracious, and engaging host. After a

bit of small talk, we got down to brass tacks.

The five of us were

passionate and firm in expressing the myriad range of responses

engendered by Dean Starr's representation of Prop. 8

supporters. Of course, Mr. Starr is more than a charmer. His

presentation buttressed his reputation as a brilliant advocate,

and it was not surprising to hear from him his very worked-out,

intellectual, and rational world view about individuals' legal

rights, constitutional frameworks, and the need to preserve

both, even at the expense of a protected minority class of

people. Because the Prop. 8 case raised issues that he felt had

the potential to threaten this sacred constitutional paradigm,

he told us that he took the case with little regard to the real

and personal impact his successful representation would have on

not only fellow Californians but also, as he called it,

"members of the Pepperdine family."

Perhaps I did fall prey

to his charming ways. Perhaps he is just a good actor. I don't

really know. What I do know is that his eyes seemed to open

when he heard from two gay alumni about how he had personally

caused anguish in their lives. As he listened, I noticed a

shift in his demeanor evidenced by a concerned look on his

face, followed by a sudden realization that flashed in his

eyes, and then it happened. He said it: "I'm sorry." He

admitted that he had not anticipated the intensity of

opposition that his representation had evoked.

Before you get too

excited, let's be clear: He did not apologize for taking the

case. But to me, it was apparent that until now he had been so

successful in compartmentalizing his legal representation,

keeping it separate from any emotional reality or

awareness of how he might personally harm a group of people

with his advocacy. He seemingly had an epiphany that this case

was about more than a constitutional point of jurisprudence. It

touched on his role in presiding over a "family" of current

and former students.

To its credit,

Pepperdine taught me to always get it in writing. I knew I

wasn't going to get a written apology, but I certainly

wasn't about to leave without some commitment as to how

Dean Starr would try to mend Pepperdine's image and reputation,

especially for those current, former, and prospective students

who do not espouse his views on Prop. 8. He promised he would

take a very personal and introspective look at his role as a

lawyer and the types of cases he takes in the future. He

explained that it is now clear to him that his actions have

hurt part of the "Pepperdine family" and affected how

many people perceive the school.

Where the dean finds

himself on such matters, the school still has a long ways to go

and the distance it needs to travel remains his responsibility.

He promised to review Pepperdine's ongoing discriminatory

stance toward gay students, including its refusal to allow a

student group to form to discuss LGBT legal issues. And he

agreed that for as long as the school's prejudicial and

religiously inspired policies toward gay and lesbian students

continue unabated they should be transparent and explained in

promotional materials so that prospective applicants are not

blindsided once they became students.

As the meeting

concluded and the deans promised to get back to us in writing

after the spring finals had concluded, I was completely

unprepared for the final shock: Ken Starr gave me a hug. It

wasn't one of those

college-dude-handshake-double-pat-on-the-back hugs. This was a

bona fide, sincere embrace with more than a suggestion of

affectivity you would get from someone you had known and cared

about for a long time. I was charmed.

Even though Mr. Starr

may have won his battle in court, it does not absolve him of

the responsibility he has to the "Pepperdine family."

It's time for him to prove to the world that both he and

Pepperdine aren't antigay and end all discriminatory practices

at the school. Now more than ever do we need a hug. But I'd

rather have equality.