Alameda is a 20-minute ride from San Francisco on a ferry that serves coffee in the morning and chardonnay at sunset, but the two cities' distinct personalities make the island seem a long way from what is arguably the country's gayest city. The place has a peculiar island conservatism -- not quite Republican because city's vote went 75% for John Kerry in 2004. It's a conservativism that brings the speed limit down to 25 mph on all roads. Slow is fast enough for Alameda; they think of all the children playing.

The 70,580 residents are an average of 38 years old and ripe for the Parent Teacher Association. Many live in Victorian houses standing in constant competition for the island's preservation award, which the upper-middle-class suburb gives each year to the home best representing those sensibilities. Alameda's now-defunct amusement park attracted city people from Oakland and San Francisco. Now they move there to amuse themselves and raise their children. The birthplace of the Popsicle and the snow cone is either strangely or fittingly the hotbed of a national argument on how public school students learn to live with others.

It started in the fall of 2007. Teachers that year asked for help dealing with bullies who made gay jokes. They thought talking about homosexuality in classrooms, while taboo, would teach children early on that homophobic behavior is not tolerated in class and endangers their peers. Margie Sherratt, acting assistant superintendent for the Alameda Unified School District, responded with an innocuous item now known as Lesson #9 -- which sounds sinister, like something from a science fiction novel.

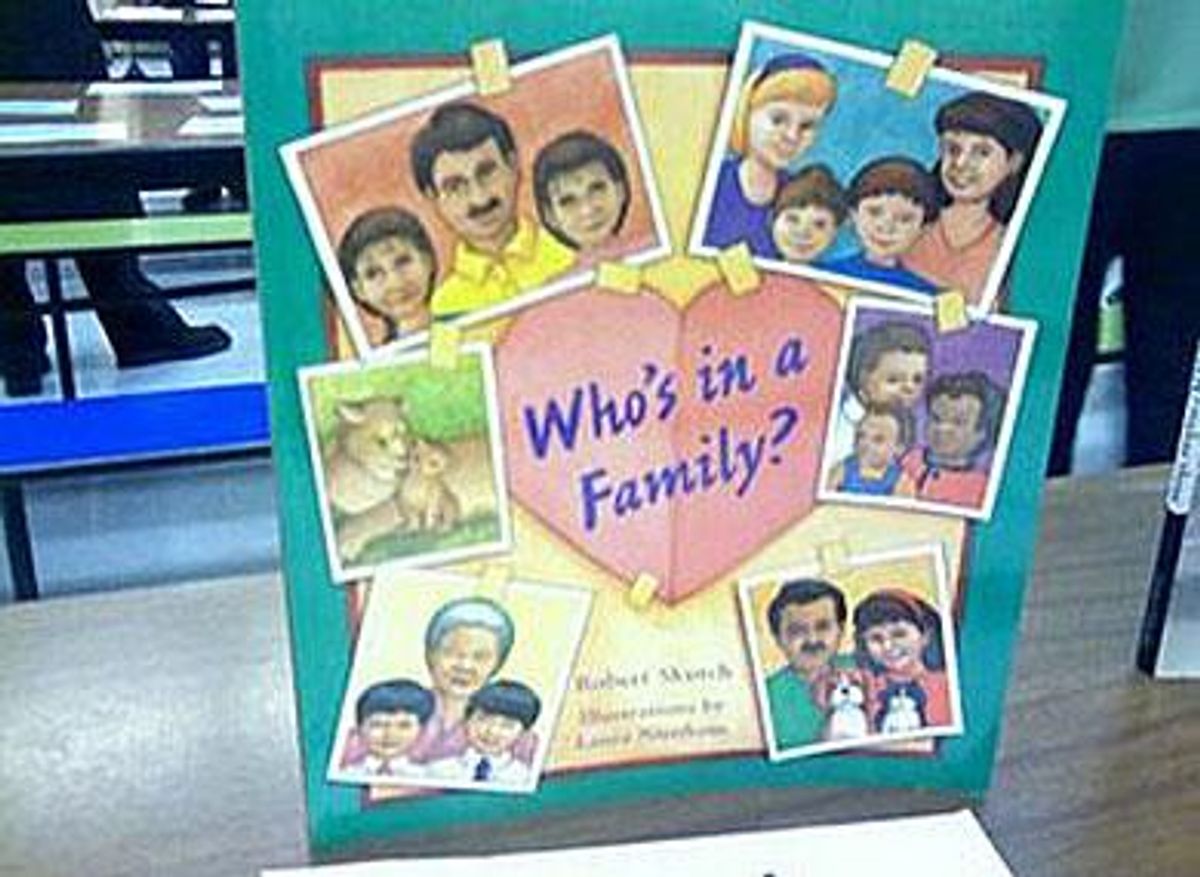

Sherratt's lesson asks kindergarten and first-grade students to define a family and introduces the idea of same-sex couples. Once able to read, students would take home the true story of Roy and Silo, two male penguins who raise a donated, fertilized egg. Older students would examine the work of Harvey Milk and poet Walt Whitman.

The curriculum recommendation has, in two years, come to represent a huge progressive step past what the state of California and all others require in their public schools with its antibullying bylaws.

It has also been the subject of controversy following the passing of California's ban on same-sex marriage; opponents of the curriculum say voters have spoken on the issue.

However, the suicides of 11-year-olds Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover in Massachusetts and Jaheem Herrera in Georgia this past spring led to a closer look at bullying -- this time as a public health hazard, suppressible with laws on the playground, state, and federal levels. Their mothers called passionately for reform as guests on Oprah Winfrey's and Ellen DeGeneres's talk shows. When they described their sons' deaths as escapes from daily torture disguised as schoolyard teasing, they became sympathetic superstars for a mini-movement.

This spring's Alameda school board meetings on the issue were packed, and parents who came to voice their opinions on the issue were often left waiting in line when the meetings had finished. The back-and-forth outgrew the board's regular chamber, so board members decided to hold the final vote, in late May, in Kaufman Auditorium, the island's largest venue. One hundred speakers signed up for the microphone and were assigned three minutes each. Crowds gathered outside feverishly waving rainbow flags; many held signs and shouted against the plan. The meeting opened as it normally would, and the board presented a motion to recognize employees of the month. Few cared.

Superintendent of schools Kirsten Vital sat in the crowded auditorium prepared to support Sherratt, argue her case, and subtly steel herself against those opposed. Parents packed the rows and lined the walls -- two camps of an agitated suburbia instinctively protecting their young.

Supporters of the item said abuse is disproportionately heaped on LGBT children. They said failure to correctly support kids who are bullied could result in unknown future trauma for the kids and that Lesson #9 satisfied the teacher's request made for increased classroom training in tolerance.

As it seemed the plan would be approved, parents pushed to pull their children from lessons, but the district's legal counsel said such lessons only warrant parental notification. California parents can say "no thanks" to health education lessons, but the lawyers said they wouldn't have that option with Lesson #9.

The board passed the item 3-2 after five hours. Supporters stood shouting and clapping while neighbors sat stunned. They filed out in polarized moods to a circus of news cameras.

Board member Tracy Jensen issued a statement saying, "This is the most divisive and contentious issue that I have faced during more than seven years as a school board member. Many of my friends, people who I have grown up with, and respected community members are on opposite sides of the debate. And all who have an opinion have a deep felt and profound need for closure. That is because we are facing a challenge as a society -- a moral challenge similar to many challenges we have overcome in the past.

"This curriculum is a small step toward doing that. We are not telling anyone what to think. We are letting children know that gay people exist and they deserve to be treated with respect, regardless of whether or not you believe that homosexuality is acceptable."

Vital told Fox News, "This is really an antibullying curriculum. Not health or sex ed, and that's why he said it's not appropriate necessarily to have an opt-out provision."

School board president Mike McMahon told the San Francisco Chronicle before the meeting that he didn't know how the board would vote.

"We assume we're going to get sued either way. We don't believe either side will be happy with the outcome," he said, deflated.

As McMahon expected, parents hired an attorney from the Pacific Justice Institute to push for an opt-out option for parents. The institute's chief counsel, Kevin Snider, represents a group of parents arguing that all protected classes should be represented in the curriculum through broader, less specific lesson plans.

"We were quite surprised that the board didn't believe that all children deserve safe schools," Snider told The Advocate. "Parents begged them."

In an interview, Eliza Byard, executive director of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, disagreed and said the Alameda board is to be commended. She said students at schools with comprehensive antibullying policies that include provisions on sexual orientation and identity reported harassment at a significantly reduced rate. Her group's research indicates that nearly nine out of 10 LGBT students (86.4%) said they had been harassed in the past year, according to GLSEN's survey of more than 6,000 LGBT students. Some 60.8% said they felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation.

***

Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover and Jaheem Herrera seem to have haunted the meetings and others like it throughout the country. One side invokes them as martyrs in an effort to gain support for antibullying measures. The other sees them as an emotional crutch that LGBT activists and allies uss to push "partial" measures on policy makers, who, they say, recognize the holes in the activists' argument but can't resist feeling something when Walker-Hoover's mother, Sirdeaner Walker, tells her story.

Walker-Hoover, an 11-year-old who played football and stayed after school for math help and whose favorite store was Staples. Herrera, an 11-year-old U.S. Virgin Islands native who enjoyed dancing like Michael Jackson. Both, according to their mothers, were ridiculed relentlessly because of to their perceived sexual orientation. Each died silently -- Walker-Hoover in early April in western Massachusetts and Herrera in early May in DeKalb County, Ga. Walker-Hoover used a extension cord and left his video games to his brother in a makeshift will that told his mother he was sorry. It wasn't far away from his body, which hung in the air above the staircase. Herrera used a cloth belt to hang himself and swayed, suspended from the closet in which his classmates accused him of living.

Walker told a congressional committee on education and labor that students called her son a faggot despite his identifying as straight.

"Hearing that, my heart just broke for him, and I was furious," she said. "I called the school right away and told them about the situation. I expected they would be just as upset as I was, but instead they told me it was just ordinary social interaction that would work itself out.

"I desperately wish they had been right. But it just got worse. By March they were threatening to kill him."

In an interview shortly after her son's suicide, Walker was angered, possessed by a grief that pointed to a school system she said failed to protect her son. Before the U.S. Congress, her plea was more solemn. She said bullying isn't a gay issue or a straight issue or about a fact of life or isolated incidents in the stairwells of working single mothers' homes. The tug-of-war is whether Alameda is teaching children too quickly or if the students can survive if they don't. Either way, Walker said she's working on a guarantee that parents won't go through what she did. The promise has influenced policy and legislation in Alameda, the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts, DeKalb County, Ga., and other school districts in the country.

A West Virginia school board decided that the state's umbrella law covering all students was specific enough and voted against including LGBT-specific language in its policies. North Carolina similarly considered including such language in the face of mounting pressure. In the state's capitol, Republican state representative Dale Folwell echoed Snider's sentiment that such policies amount to discrimination in favor of LGBT people.

"The people of North Carolina are being bullied on this floor tonight," Folwell, a former school board member, said from under the capitol's dome.

Democrats, like supporters of Alameda's lesson, accused Folwell and other Republicans of voting with their prejudices.

Rep. Grier Martin said "to oppose this bill because you object to one of those categories is to fight the culture wars on the back of a child."

Candi Cushman, an education analyst for Focus on the Family, said parents have the right to raise their children according to their own beliefs. When Cushman was told in an interview that Walker's son was a devout Christian and believed to be saved through his baptism but sentenced to what he described as a personal hell each day, she restated that all children should be protected equally.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 39 states have antibullying laws in place. According to GLSEN, however, only 11 of those, plus the District of Columbia, specifically address bullying based on sexual orientation, and only seven of them include gender identity.

The state laws, which all public schools have to obey, could be supplemented by the federal Safe Schools Improvement Act, which is winding its way through the legislative process. Meanwhile, elected representatives and school officials debate what authority they have in it all. Like Alameda, some could use state laws as a launching pad for other programs. Or there's the West Virginia method that perceives state laws as limits.

Linda Sanchez, a U.S. representative from California and the sponsor of an LGBT-specific amendment to the Safe Schools Improvement Act, is attempting to eliminate confusion by bringing all states under the same federal law. She agreed that all students should be protected, but she added that report after report indicates physical, racial, and sexual minority groups are more often victimized. She said the law should needs to include specific protection for LGBT students and other groups to make sure the classroom actually is equal in practice as well in theory.

Dorothy Espelage, a professor in the educational psychology department at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said unchecked violence toward children often makes the victims become violent themselves.

"We're seeing suicides at such a young age because there are limited mental health resources in our schools to help these children, and they turn to suicide because they lack the physical and cognitive ability to contemplate violence against their perpetrators such as planning a school shooting," she said.

Sanchez said Alameda is trying to prevent this early.

"It's really time for us to sit up and take notice -- to be responsible and stop this before it starts," she said.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered