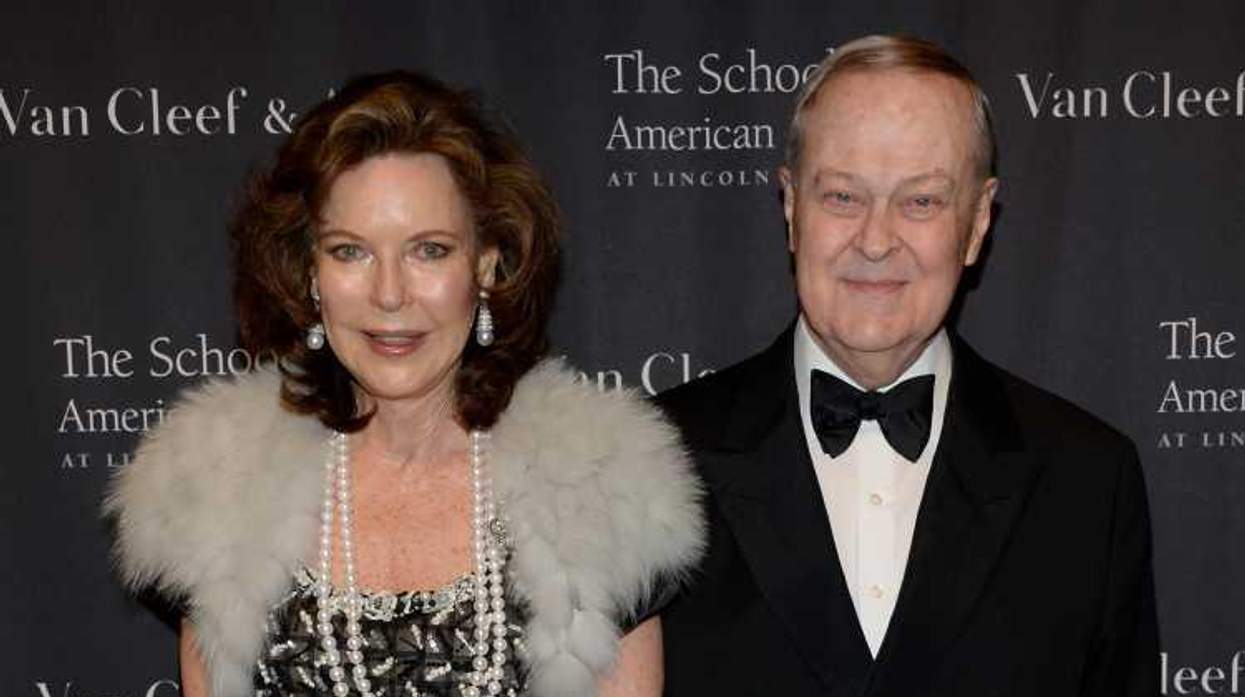

Frederick Koch, whose brothers financed right-wing causes and reportedly attempted to blackmail him when they suspected he was gay, has died at age 86.

Koch, who did not share his brothers' business or political interests but focused on collecting art and restoring houses, died Wednesday of heart failure at his home in Manhattan, The New York Times reports.

He was the oldest of four brothers, two of whom, Charles and David, became famous for bankrolling conservative causes with the fortune they derived from Koch Industries, which had holdings in oil and many other businesses. David Koch died last year at age 79.

Jane Mayer's book Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, published in 2016, detailed a blackmail plot against Frederick.

"You have to remember this was a very long time ago, when the idea of being gay was considered scandalous in a family, particularly a family of rough, self-made oil men out in Wichita, Kan.," she told NPR that year. "It was considered a dark secret that first-born son Frederick might have been gay. At some point, when Frederick was in his 20s, all four of the sons by then had shares in the family company. And what the three other brothers did was they created a kind of kangaroo court ... so that [Frederick] walked into a room, found his three other brothers sitting there in chairs facing him, and they confronted him and conducted an inquisition to see if he was gay. And they then said that if he was, they were going to tell their father unless he handed over his share in the company. ...

"It's been rumored about for years in other write-ups about the Kochs, and there have been various descriptions of people denying it, but I actually got a hold of a sealed deposition in which one of the brothers, Bill Koch, describes the whole thing as it unfolded. The brother who they were accusing -- Frederick, who was the eldest -- stood up, looked at them, said, 'I never want to hear about this again,' and walked out of the room. It didn't work. But as a ploy, I think it gives you an idea of a family that is not the usual cozy, all-American family."

For the record, Frederick, who was named for his father, repeatedly denied that he was gay. Daniel Schulman, author of the 2014 book Sons of Wichita: How the Koch Brothers Became America's Most Powerful and Private Dynasty, described Frederick's homosexuality as "an open secret" among the family and their friends. But Frederick told him, "Charles's 'homosexual blackmail' to get control of my shares did not succeed for the simple reason that I am not homosexual."

Still, it's clear that most of the Koch family did not have gay people's best interests at heart. David and Charles's donations have focused on economic matters, such as advocating for lower taxes and fewer corporate regulations, and David publicly supported marriage equality, but they contributed to anti-LGBTQ politicians such as Mike Pence, in both of his campaigns for Indiana governor.

They also have funded the American Legislative Exchange Council, known by the acronym ALEC, a conservative group that drafts model legislation for states with the goals of cutting taxes, opposing gun restrictions, weakening labor unions, and repealing regulations on business. In addition, ALEC has drafted many laws criminalizing HIV exposure and, at least in its early years, strongly opposed LGBTQ equality.

"David Koch may say he supports marriage equality but every political check he's written says the exact opposite," Advocate executive editor Neal Broverman wrote in 2014.

Frederick Koch had little contact with his brothers as an adult, except in court, the Times obituary notes. Bill Koch did enlist Frederick's help in an attempt to take Koch Industries public in the 1980s, resisted by Charles and David, which resulted in a lawsuit that was settled out of court. After many years of legal wrangling, "Bill and Frederick eventually reconciled with David, but not with Charles," according to the Times.

Bill and Charles Koch are Frederick's only immediate survivors. Frederick's entire estate will be used to establish an arts foundation, the Times reports.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes