Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the "don't say gay" bill into law in March (although a federal lawsuit has been filed challenging its constitutionality), barring discussion about sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through grade 3 and requiring "age-appropriate" discussion after that while not defining what that actually constitutes.

Many see the law -- formally known as the Parental Rights in Education law -- as dangerous and harmful, especially for LGBTQ+ kids, as Will Larkins, a gay nonbinary high school junior and activist in Winter Park, Fla., explained in their guest op-ed for the New York Times titled "Florida's 'Don't Say Gay' Bill Will Hurt Teens Like Me."

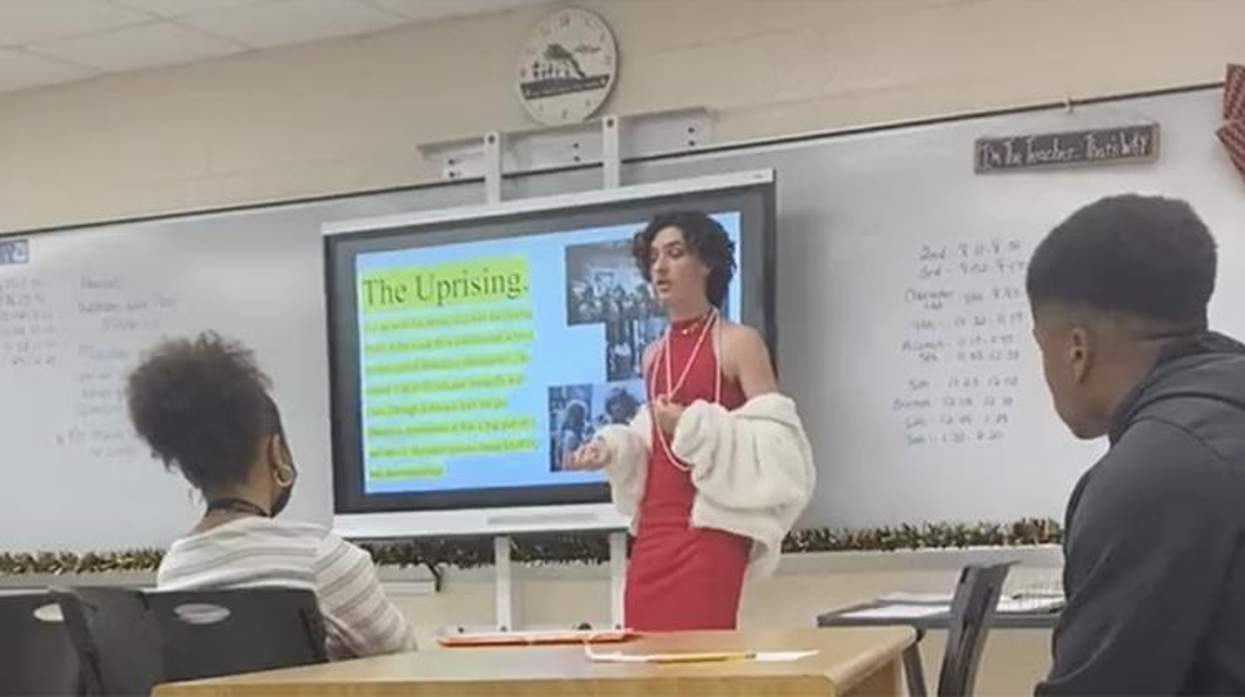

Larkins is also doing some education of their own. In a video posted to Twitter on April 3, Larkins shared that they had given a presentation to their U.S. history class about queer history. "LGBTQ American history is not taught in Florida's public schools, so I took it upon myself to explain the events of the Stonewall Uprising to my 4th period US history class," wrote Larkins.

Their video has been seen more than 400,000 times as of Tuesday morning.

The post drew both praise and criticism, leading Larkins to give further context to the clip. "We were in the late 60s early 70s unit and when I found out we were gonna learn about stonewall (1969) I made a presentation and my teacher let me show the class," they explained, while also trying to push back on negative comments they received. "I'm a 17-year-old high school junior teaching a historical event to my classmates. We have learned much more intense history in this class. How are y'all calling me a groomer and a pedo rn. Stop sexualizing and harassing minors like me."

In an interview with The Washington Post, Larkins said they had been motivated to do the presentation after asking their teacher if they would be covering Stonewall in class. Larkins told the paper that the teacher responded, "What's Stonewall?"

They then put together a presentation for the teacher and was then allowed to present about the pivotal LGBTQ+ rights moment to the class. "We don't learn queer history at all," Larkins said. "It felt like something important that needed to happen, especially with the legislation in Florida."

In their piece for the Times, Larkins opened up about how early in their childhood they knew they were "different", along with the pain and confusion that caused. "I wasn't interested in the things other boys my age did, and I didn't really feel comfortable in the clothes my parents bought me. The struggle for acceptance was not just internal, it also felt as if my classmates didn't know what to make of me. By fourth grade I was convinced that I was broken," Larkins wrote.

It wasn't until they learned about what it meant to be LGBTQ+ that they stopped feeling totally alone. This led them to speculate how different things could have been for them had they learned about different gender identities and sexuality at an earlier age. "When I look back to elementary school, I wonder how different my childhood would have been had my classmates and I known that I wasn't some tragic anomaly, a strange fluke that needed to be fixed. People in support of the bill always ask, 'Why do these subjects need to be taught in schools?' To them, I would say that if we understand ourselves, and those around us understand us, so many lives will be saved."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes