Nikki Giovanni, the renowned poet and Black queer icon, has died at age 81.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

Giovanni died Monday in a hospital in Blacksburg, Va., her wife, Virginia C. Fowler, told The New York Times. The cause was complications of lung cancer.

Giovanni was a major figure in the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Much of her work at the time dealt with civil rights and the atrocities committed against Black Americans, such as the lynching of Emmett Till, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the Birmingham, Ala., church bombing of 1963, in which four young girls were killed.

She published her first books of poetry, Black Judgement and Black Feeling, Black Talk, in 1968. She wrote poetry for children as well as adults, and she penned essays and made recordings. She authored a memoir, Gemini: An Extended Autobiographical Statement on My First Twenty-Five Years of Being a Black Poet, which came out in 1971, when she was only 28. Giovanni often gave public readings of her poems, usually appearing alongside gospel choirs and other musicians, and these performances attracted huge audiences around the nation.

“My dream was not to publish or to even be a writer: my dream was to discover something no one else had thought of,” Giovanni wrote on her website. “I guess that’s why I’m a poet. We put things together in ways no one else does.”

After finishing college at Fisk University, she was at a crossroads. “I had no money; no patience with stupid jobs; no talent that could be sold,” she noted on the site. She attended graduate school for a time, but she ended up self-publishing her first books because “no one was much interested in a Black girl writing what was called ‘militant’ poetry.”

So her career was launched, with many appearances onstage and on television. She was a fixture of the public TV program Soul!, for which she conducted a two-part interview with Black gay writer James Baldwin in 1971. “Two of the most important artist-intellectuals of the twentieth century were engaged in intimate communion on national television,” The New Yorker wrote.

“As one of the cultural icons of the Black Arts and Civil Rights Movements, she became friends with Rosa Parks, Aretha Franklin, James Baldwin, Nina Simone, and Muhammad Ali, and inspired generations of students, artists, activists, musicians, scholars and human beings, young and old,” a friend, writer Renée Watson, said in a statement announcing Giovanni’s death.

Much of Giovanni’s later work was more personal than political, celebrating strong Black women, their homes, and Black joy. “It was a voice you didn’t hear a lot then, this desire for home,” cultural critic Hilton Als told the Times about hearing her read her poem “My House” in the early 1970s. “Later, as she ditched the Black nationalist rhetoric, she became more herself. She was saying something really profound to me, a member of the gay community and the Black world and whatever. She was the first warrior in terms of talking about queer love — not specifically, but it was there.”

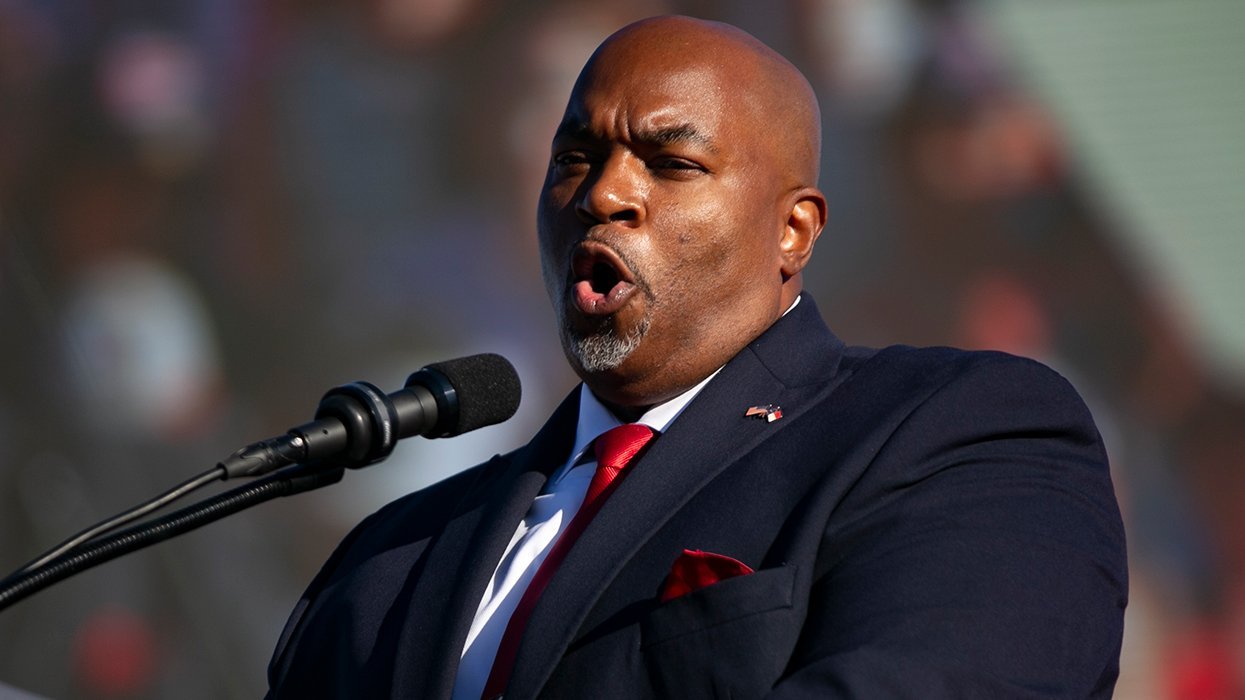

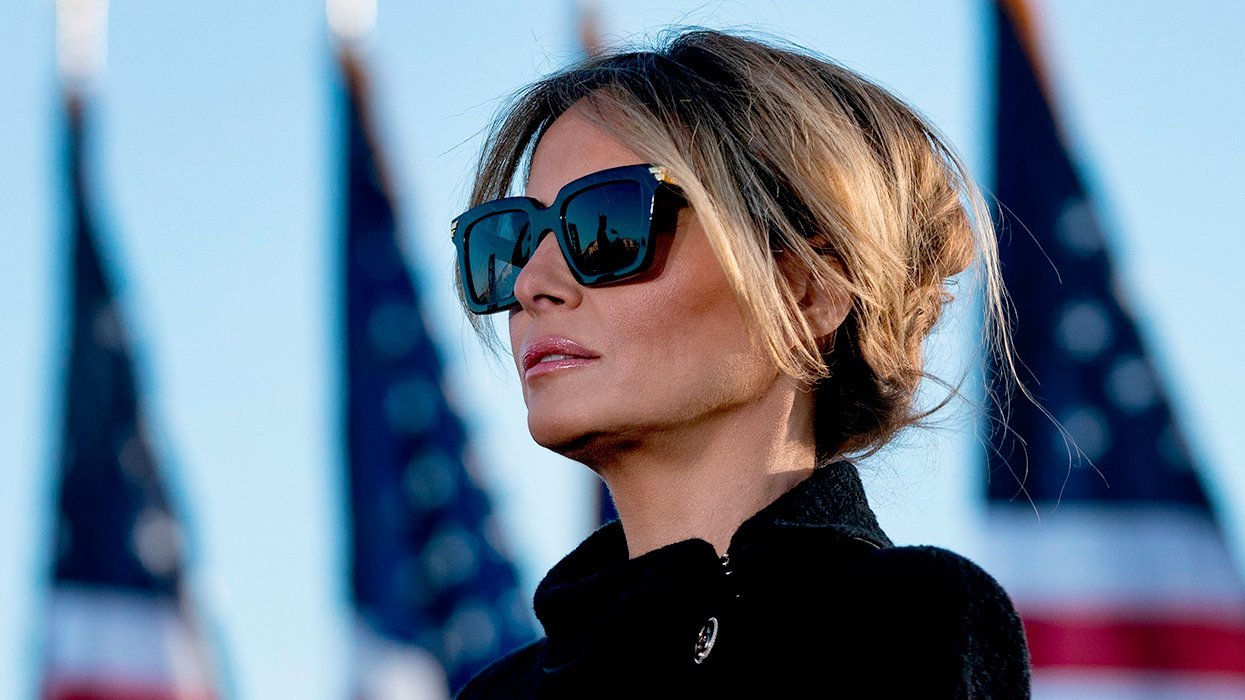

Murray Feierberg/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

Murray Feierberg/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

Giovanni also taught, first at Rutgers University and Queens College, and then Fowler recruited her to Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, where she began teaching in 1987 and remained until her retirement in 2022. They quickly developed a personal and professional relationship, with Fowler becoming an editor and scholar of Giovanni’s work and writing a biography of her, Nikki Giovanni, which came out in 2013. They married in 2016.

At Virginia Tech, Giovanni was the first person to alert administrators to the threatening behavior of student Seung-Hui Cho, who shot and killed 32 people at the university in 2007, then took his own life. "When Giovanni approached the English department chair to have Cho expelled from her class, Giovanni said she would rather resign than continue teaching him," the Rev. Irene Monroe wrote in The Advocate shortly after the tragedy. "Depicting Cho as 'a bully," Giovanni told The Washington Post, 'Kids write about murder and suicide all the time. But there was something that made all of us pay attention closely. His was more sinister. None of us were comfortable with that. ... Once I realized my class was scared, I knew I had to do something.'"

Giovanni spoke at the ceremony memorializing the Virginia Tech victims, saying, "We are strong, and brave, and innocent, and unafraid. We are better than we think and not quite what we want to be. We are alive to the imaginations and the possibilities. We will continue to invent the future through our blood and tears and through all our sadness." Monroe called Giovanni "a neglected and overlooked heroine in our queer community."

Giovanni had one child, a son, Thomas, born in 1969. She said she was single (at the time) by choice and a mother by choice; she never revealed publicly who Thomas’s father was. “I had a baby at 25 because I wanted to have a baby and I could afford to have a baby,” she once told Ebony magazine. “I didn’t get married because I didn’t7 want to get married and I could afford to not get married.”

She was put off by the sexist attitudes of some Black men and wondered if men and women were really suited to each other. “Maybe they have a different thing going,” she wrote, “where they come together during mating season and produce beautiful, useless animals who then go on to love, you hope, each of you.” But she found lasting love with Fowler, who she described as her “bench,” her supporter.

“I don’t have a lot of friends but I have good ones,” Giovanni wrote on her website. “I have a son and a granddaughter. My father, mother, sister and middle aunt are all deceased literarily making me go from being the baby in the family to being an elder. I like to cook, travel and dream. I’m a writer. I’m happy.”

She received seven NAACP Image Awards, 31 honorary doctorates, and a 2024 Emmy, the latter for Exceptional Merit in Documentary Filmmaking for Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project. She had three books on the Los Angeles Times and New York Times best-seller lists, “highly unusual for a poet,” she noted on her site. She was still writing at the end of her life; her final work, titled The Last Book, is scheduled to come out next year.