One hundred years ago, on December 10, 1924, the first legally recognized U.S. gay rights organization was incorporated: the Society for Human Rights, located in Chicago.

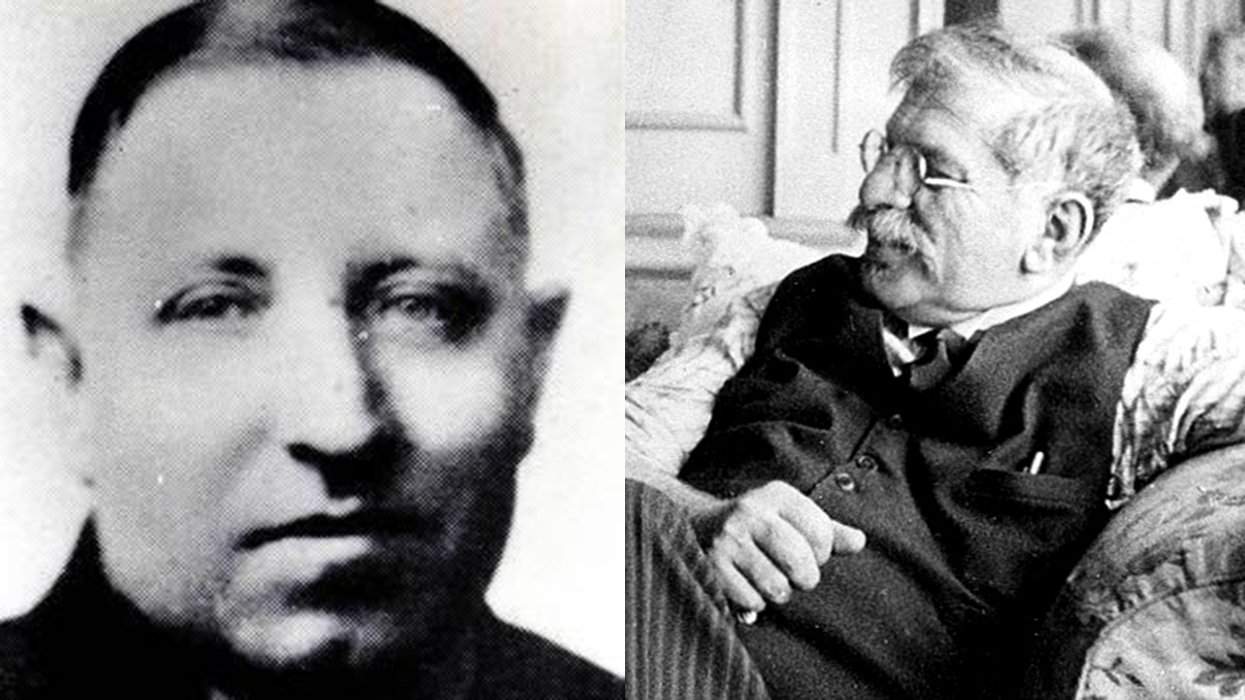

The founder was Henry Gerber, a German immigrant and postal worker. In his native country, he had been expelled from school and lost several jobs for being gay, according to the biography An Angel in Sodom: Henry Gerber and the Birth of the Gay Rights Movement by Jim Elledge, published in 2022.

He came to the U.S. with his family in 1913, at age 21, and enlisted in the Army. After he completed his service, he became involved in Chicago’s gay scene, but that led to more trouble — institutionalization, arrests, and being interned as an enemy alien. The authorities gave him the choice of being imprisoned or going back to the Army.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

He chose the latter, and his assignment returned him to Germany in 1920. There he found a major gay rights movement had emerged. “He subscribed to German homophile magazines and was in contact with Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Community in Berlin,” notes a bio on the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame website. Inspired, when back in the U.S. and working for the postal service, he decided to start a movement in his adopted country. He and his friends incorporated the nonprofit Society for Human Rights. The group published a newsletter, Friendship and Freedom.

Unfortunately, the society didn’t last long. In July 1925, family members of one of Gerber’s associates reported the group to police, who raided a meeting of the society, arrested Gerber and others, and searched Gerber’s apartment, confiscating materials related to the organization. Gerber spent his life savings on his defense, and after three trials the charges against him were dismissed on the grounds that he had been arrested without a warrant. He was fired from the postal service, and he moved to New York City and rejoined the Army, serving another 17 years — the military apparently being more tolerant of homosexuality at the time than many civilian employers.

Gerber’s activism later in life was lower-profile. He formed a correspondence club for gay men and wrote articles and letters to the editor under a pseudonym. After World War II, he moved to a home for military retirees in Washington, D.C., and he eventually he joined the Washington chapter of a new gay rights group, the Mattachine Society. Harry Hay founded Mattachine in California in 1950, having taken inspiration from Gerber. But Gerber’s involvement with the later gay rights movement was limited by his “deep-rooted crankiness,” which “left him unsatisfied with what the new generation of advocates were doing,” Patrick T. Reardon wrote in a review of An Angel in Sodom.

Gerber wrote several books, all unpublished, and one of them, the novella Angels in Sodom, gave Elledge the title for his biography. Gerber also wrote a remembrance of the Society for Human Rights for ONE Magazine in 1962. The ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries in Los Angeles has a collection of Gerber’s letters, which proved valuable to Elledge for his book.

The Gerber/Hart LGBTQ+ Library and Archives in Chicago, founded in 1981, is named in honor of Gerber and Pearl Hart, an activist lawyer who defended gays and immigrants. Gerber/Hart has a free lending library of books, e-books, and audiovisual materials as well as an archive of documents.

Gerber died in 1972 at age 80. He was inducted posthumously into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 1992, and in 2015, his apartment building in Chicago was designated a National Historic Landmark by Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell. It was only the second LGBTQ+ site to receive the title — the first was the Stonewall Inn in New York City, where the famous riots against police harassment took place in 1969.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes